|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

October 2017 -

Volume 15, Issue 8

|

|

|

View

this issue in pdf formnat - the issue

has been split into two files for downloading

due to its large size: FULLpdf

(12 MB)

Part

1 &

Part

2

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

........................................................

|

|

Original Contribution/Clinical Investigation

Immunity

level to diphtheria in beta thalassemia patients

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93048

[pdf

version]

Abdolreza Sotoodeh Jahromi, Karamatollah Rahmanian,

Abdolali Sapidkar, Hassan Zabetian, Alireza

Yusefi, Farshid Kafilzadeh, Mohammad Kargar,

Marzieh Jamalidoust,

Abdolhossein Madani

Genetic

Variants of Toll Like Receptor-4 in Patients

with Premature Coronary Artery Disease, South

of Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93049

[pdf

version]

Saeideh Erfanian, Mohammad Shojaei, Fatemeh

Mehdizadeh, Abdolreza Sotoodeh Jahromi, Abdolhossein

Madani, Mohammad Hojjat-Farsangi

Comparison

of postoperative bleeding in patients undergoing

coronary artery bypass surgery in two groups

taking aspirin and aspirin plus CLS clopidogrel

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93050

[pdf

version]

Ali Pooria, Hassan Teimouri, Mostafa Cheraghi,

Babak Baharvand Ahmadi, Mehrdad Namdari, Reza

Alipoor

Comparison

of lower uterine segment thickness among nulliparous

pregnant women without uterine scar and pregnant

women with previous cesarean section: ultrasound

study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93051

[pdf version]

Taravat Fakheri, Irandokht Alimohammadi, Nazanin

Farshchian, Maryam Hematti,

Anisodowleh Nankali, Farahnaz Keshavarzi, Soheil

Saeidiborojeni

Effect

of Environmental and Behavioral Interventions

on Physiological and Behavioral Responses of

Premature Neonates Candidates Admitted for Intravenous

Catheter Insertion in Neonatal Intensive Care

Units

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93052

[pdf

version]

Shohreh Taheri, Maryam Marofi, Anahita Masoumpoor,

Malihe Nasiri

Effect

of 8 weeks Rhythmic aerobic exercise on serum

Resistin and body mass index of overweight and

obese women

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93053

[pdf

version]

Khadijeh Molaei, Ahmad Shahdadi, Reza Delavar

Study

of changes in leptin and body mass composition

with overweight and obesity following 8 weeks

of Aerobic exercise

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93054

[pdf

version]

Khadijeh Molaei, Abbas Salehikia

A reassessment

of factor structure of the Short Form Health

Survey (SF-36): A comparative approach

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93088

[pdf version]

Vida Alizad, Manouchehr Azkhosh, Ali Asgari,

Karyn Gonano

Population and Community Studies

Evaluation

of seizures in pregnant women in Kerman - Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93056

[pdf

version]

Hossein Ali Ebrahimi, Elahe Arabpour, Kaveh

Shafeie, Narges Khanjani

Studying

the relation of quality work life with socio-economic

status and general health among the employees

of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS)

in 2015

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93057

[pdf version]

Hossein Dargahi, Samereh Yaghobian, Seyedeh

Hoda Mousavi, Majid Shekari Darbandi, Soheil

Mokhtari, Mohsen Mohammadi, Seyede Fateme Hosseini

Factors

that encourage early marriage and motherhood

from the perspective of Iranian adolescent mothers:

a qualitative study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93058

[pdf

version]

Maasoumeh Mangeli, Masoud Rayyani, Mohammad

Ali Cheraghi, Batool Tirgari

The

Effectiveness of Cognitive-Existential Group

Therapy on Reducing Existential Anxiety in the

Elderly

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93059

[pdf

version]

Somayeh Barekati, Bahman Bahmani, Maede Naghiyaaee,

Mahgam Afrasiabi, Roya Marsa

Post-mortem

Distribution of Morphine in Cadavers Body Fluids

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93060

[pdf

version]

Ramin Elmi, Mitra Akbari, Jaber Gharehdaghi,

Ardeshir Sheikhazadi, Saeed Padidar, Shirin

Elmi

Application

of Social Networks to Support Students' Language

Learning Skills in Blended Approach

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93061

[pdf

version]

Fatemeh Jafarkhani, Zahra Jamebozorg, Maryam

Brahman

The

Relationship between Chronic Pain and Obesity:

The Mediating Role of Anxiety

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93062

[pdf

version]

Leila Shateri, Hamid Shamsipour, Zahra Hoshyari,

Elnaz Mousavi, Leila Saleck, Faezeh Ojagh

Implementation

status of moral codes among nurses

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93063

[pdf

version]

Maryam Ban, Hojat Zareh Houshyari Khah, Marzieh

Ghassemi, Sajedeh Mousaviasl, Mohammad Khavasi,

Narjes Asadi, Mohammad Amin Harizavi, Saeedeh

Elhami

The comparison

of quality of life, self-efficacy and resiliency

in infertile and fertile women

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93064

[pdf version]

Mahya Shamsi Sani, Mohammadreza Tamannaeifar

Brain MRI Findings in Children (2-4 years old)

with Autism

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93055

[pdf

version]

Mohammad Hasan Mohammadi, Farah Ashraf Zadeh,

Javad Akhondian, Maryam Hojjati,

Mehdi Momennezhad

Reviews

TECTA gene function and hearing: a review

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93065

[pdf version]

Morteza Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori, Fahimeh Moradi,

Raziyeh Karami-Eshkaftaki,

Samira Asgharzade

Mandibular

canal & its incisive branch: A CBCT study

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93066

[pdf

version]

Sina Haghanifar, Ehsan Moudi, Ali Bijani, Somayyehsadat

Lavasani, Ahmadreza Lameh

The

role of Astronomy education in daily life

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93067

[pdf

version]

Ashrafoalsadat Shekarbaghani

Human brain

functional connectivity in resting-state fMRI

data across the range of weeks

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93068

[pdf version]

Nasrin Borumandnia, Hamid Alavi Majd, Farid

Zayeri, Ahmad Reza Baghestani,

Mohammad Tabatabaee, Fariborz Faegh

International Health Affairs

A

brief review of the components of national strategies

for suicide prevention suggested by the World

Health Organization

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93069

[pdf

version]

Mohsen Rezaeian

Education and Training

Evaluating

the Process of Recruiting Faculty Members in

Universities and Higher Education and Research

Institutes Affiliated to Ministry of Health

and Medical Education in Iran

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93070

[pdf

version]

Abdolreza Gilavand

Comparison

of spiritual well-being and social health among

the students attending group and individual

religious rites

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93071

[pdf

version]

Masoud Nikfarjam, Saeid Heidari-Soureshjani,

Abolfazl Khoshdel, Parisa Asmand, Forouzan Ganji

A

Comparative Study of Motivation for Major Choices

between Nursing and Midwifery Students at Bushehr

University of Medical Sciences

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93072

[pdf

version]

Farzaneh Norouzi, Shahnaz Pouladi, Razieh Bagherzadeh

Clinical Research and Methods

Barriers

to the management of ventilator-associated pneumonia:

A qualitative study of critical care nurses'

experiences

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93073

[pdf version]

Fereshteh Rashnou, Tahereh Toulabi, Shirin Hasanvand,

Mohammad Javad Tarrahi

Clinical

Risk Index for Neonates II score for the prediction

of mortality risk in premature neonates with

very low birth weight

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93074

[pdf

version]

Azadeh Jafrasteh, Parastoo Baharvand, Fatemeh

Karami

Effect

of pre-colporrhaphic physiotherapy on the outcomes

of women with pelvic organ prolapse

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93075

[pdf

version]

Mahnaz Yavangi, Tahereh Mahmoodvand, Saeid Heidari-Soureshjani

The

effect of Hypertonic Dextrose injection on the

control of pains associated with knee osteoarthritis

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93076

[pdf

version]

Mahshid Ghasemi, Faranak Behnaz, Mohammadreza

Minator Sajjadi, Reza Zandi,

Masoud Hashemi

Evaluation

of Psycho-Social Factors Influential on Emotional

Divorce among Attendants to Social Emergency

Services

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93077

[pdf

version]

Farangis Soltanian

Models and Systems of Health Care

Organizational

Justice and Trust Perceptions: A Comparison

of Nurses in public and private hospitals

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93078

[pdf

version]

Mahboobeh Rajabi, Zahra Esmaeli Abdar, Leila

Agoush

Case series and Case reports

Evaluation

of Blood Levels of Leptin Hormone Before and

After the Treatment with Metformin

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93079

[pdf

version]

Elham Jafarpour

Etiology,

Epidemiologic Characteristics and Clinical Pattern

of Children with Febrile Convulsion Admitted

to Hospitals of Germi and Parsabad towns in

2016

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93080

[pdf

version]

Mehri SeyedJavadi, Roghayeh Naseri, Shohreh

Moshfeghi, Irandokht Allahyari, Vahid Izadi,

Raheleh Mohammadi,

Faculty development

The

comparison of the effect of two different teaching

methods of role-playing and video feedback on

learning Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93081

[pdf

version]

Yasamin Hacham Bachari, Leila Fahkarzadeh, Abdol

Ali Shariati

Office based family medicine

Effectiveness

of Group Counseling With Acceptance and Commitment

Therapy Approach on Couples' Marital Adjustment

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2017.93082

[pdf

version]

Arash Ziapour, Fatmeh Mahmoodi, Fatemeh Dehghan,

Seyed Mehdi Hoseini Mehdi Abadi,

Edris Azami, Mohsen Rezaei

|

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| October 2017 -

Volume 15, Issue 8 |

|

|

Barriers to the management

of ventilator-associated pneumonia: A qualitative

study of critical care nurses’ experiences

Fereshteh Rashnou

(1)

Tahereh Toulabi (2,3)

Shirin Hasanvand (2,3)

Mohammad Javad Tarrahi (4)

(1) Student Research Committee, Lorestan

University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad,

Iran.

(2) Social Determinants of Health Research Center,

Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad,

Iran.

(3) School of Nursing& Midwifery, Lorestan

University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad,

Iran.

(4) Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics,

School of Health, Isfahan University of Medical

Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Correspondence:Tahereh Toulabi, Social Determinants

of Health Research Center, Lorestan University

of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran.

Phone numbers: +989161613969 - +986633120140

Fax: +986633120140

Email: tolabi.t@lums.ac.ir

|

Abstract

Background & Aims: Ventilator-associated

pneumonia (VAP) is associated with serious

complications such as morbidity and mortality,

prolonged hospital stay, and great financial

burden. The purpose of this study was

to explore critical care nurses’

experiences of the barriers to VAP management.

Materials &

Methods: This descriptive qualitative

study was done in 2015 using the conventional

content analysis approach. A purposive

sample of twelve critical care nurses

was selected. Data were collected through

unstructured interviews and focus group

discussions. Graneheim and Lundman’s

qualitative content analysis was employed

for data analysis. The trustworthiness

of the data and the findings was ensured

by adopting the criteria proposed by Lincoln

and Guba.

Results:

The major barriers to VAP management were

low quality of working life and poor organizational

culture.

Conclusion:

Nurses can help manage effective VAP through

learning new and standard approaches to

care delivery and adhering to standards

of care.

Key words:

VAP management, Quality of working life,

Organizational culture

|

Nosocomial infections are a major global health

problem (1, 2) and the commonest complication

of hospital care (3). The most prevalent and

fatal nosocomial infection in intensive care

units (ICUs) is ventilator-associated pneumonia

(VAP) (4). The prevalence of VAP is as high

as 9%–27% (5).

Intubated patients rapidly develop VAP within

the first five days after intubation (5, 6).

The risk factors for VAP are numerous and include

accumulation of secretions behind the cuff of

the endotracheal tube, impaired cough reflex,

reduced ciliary activity, immobility, lying

in the supine position (7), aging, underlying

conditions, altered consciousness, endotracheal

intubation, poor nutrition, healthcare workers’

poor hand hygiene (8), hypoxia, naso-gastric

tube, acidosis, pulmonary edema, immunosuppression

(9), burns, disorders of the central nervous

system, severity of the underlying conditions,

re-intubation, and surgery (10).

VAP extends the duration of mechanical ventilation,

prolongs ICU and hospital stay (11 and 12),

and expands hospital staff’s workload (11).

Besides, it is responsible for half of all antibiotic

prescriptions for patients receiving mechanical

ventilation (8) and imposes a heavy financial

burden on patients and healthcare systems (13).

According to Lawrence and Fulbrook (2011), VAP

adds to the cost of hospital care by 40,000

US dollars per patient per hospital admission

(14).

Given the serious complications of VAP and

the priority of prevention over treatment, VAP

prevention is the most cost-effective and optimal

way for fighting VAP (15). Studies have shown

that one third of all nosocomial infections

such as VAP are preventable (16). Currently,

VAP prevention is considered as one of the key

components of patient safety guidelines (4),

a main safety goal (17), and a quality improvement

indicator in most healthcare systems, and a

criterion for evaluating ICUs (18).

Despite many efforts for controlling VAP, its

incidence rate is still very high and it is

the most fatal nosocomial infection. Consequently,

prevention and management of VAP necessitate

continuous monitoring (19), effective problem

assessment, and all-party support. According

to Lambert et al. (2013), all hospital staff

need to receive continuing education about VAP

management. Moreover, preventive measures should

be designed to improve the quality of hospital

care (17).

Nurses are the most important component of

nosocomial infection prevention programs (20).

As healthcare providers who have constant presence

in clinical settings, nurses have significant

roles in preventing and managing health problems

and providing care to patients. In addition,

implementing VAP prevention strategies is among

the key responsibilities of nurses. Thus, exploring

their experiences is of great importance. Nonetheless,

most of the previous studies into VAP prevention

had been done by using quantitative designs,

leaving nurses’ experiences of VAP prevention

poorly explored, if at all. The present study

was made to bridge this gap. The purpose of

the study was to explore critical care nurses’

experiences of the barriers to VAP management.

Design

This descriptive qualitative study was done

by using the conventional content analysis approach

(21).

Setting

The study was conducted in 2015 in a teaching

hospital located in Lorestan Province, Iran.

Participants

Sampling was done through purposeful sampling

and was continued until reaching data saturation

(22). Consequently, twelve critical care nurses

were selected. Nurses were included if they

had at least a bachelor’s degree in nursing,

minimum work experience in ICUs of three months,

desire for sharing their experiences, and stable

psychological state for establishing communication.

We excluded them if they voluntarily withdrew

from the study or avoided sharing their experiences.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were carried out

with twelve nurses for data collection, each

of which lasted 30 minutes, on average. Besides,

we held two focus group discussions. The size

of each focus group was six nurses and the length

of the discussions was 25 minutes, on average.

Focus group discussions help collect data from

a large sample of participants in a short period

of time while semi-structured personal interviews

provide a deeper understanding of the intended

phenomenon (23). Broad open-ended interview

questions were employed to delve into the participants’

experiences. Some of the interview questions

were: “What care measures do you use to

prevent VAP?” “How does the physical

structure of your unit affect VAP management?”

“How do the facilities and equipment in

your unit affect VAP management?” “What

are the barriers to VAP management in your unit?”

“What are the facilitators to VAP management

in your unit?” Besides these main interview

questions, follow-up questions were also asked

to clarify ambiguities in experiences shared

by the participants. The interviews and the

focus group discussions were recorded digitally

using a MP3 recorder.

Data analysis

Concurrently with data collection, we performed

data analysis by pursuing the Graneheim and

Lundman’s five-step approach to content

analysis (21). Immediately after holding each

interview, it was transcribed word by word and

read for several times. Then, primary codes

were extracted, compared and merged with each

other, and grouped into categories based on

their similarities.

Rigor and data trustworthiness

The credibility of the data was maintained through

employing the member checking technique, allocating

adequate time to data collection, and arranging

the interviews based on the interviewees’

preferences. Moreover, confirmability was ensured

through sending the interviews, codes, and categories

to several external reviewers and asking them

to assess the accuracy of data analysis, while

dependability was maintained by immediate transcription

and analysis of each interview. The maximum

variation sampling was also employed to enhance

the transferability of the findings (24).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained

from the Ethics Committee of Lorestan University

of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran. After

explaining the aim and the methods of the study

to the participants, their informed consent

for participation in the study and recording

their interviews was secured. They were ensured

that their information would be treated as confidential

and they would have access to the findings.

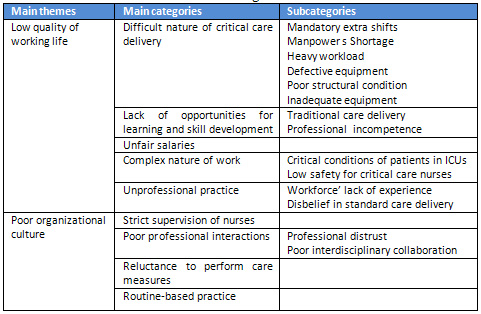

Most

of

the

participants

were

female

(10

cases).

The

means

of

their

age

and

professional

experience

were

25.3

and

4.6

years,

respectively.

Their

experiences

of

the

barriers

to

VAP

management

came

into

two

main

themes

of

low

quality

of

working

life

and

poor

organizational

culture

which

are

shown

in

Table

1

and

explained

in

what

follows.

Table

1:

Main

themes,

categories

and

subcategories

of

critical

care

nurses’

experiences

of

the

barriers

to

VAP

management

A.

Low

quality

of

working

life

Quality

of

working

life

(QWL)

is

the

result

of

workers’

satisfaction

with

their

needs

and

is

achieved

through

attending

workplaces.

In

healthcare

organizations,

QWL

is

among

the

principal

factors

behind

the

quality

of

workers’

performance

and

care.

According

to

our

participants,

low

QWL

was

among

the

main

barriers

to

effective

VAP

management.

The

five

main

categories

of

this

main

theme

were

difficult

nature

of

critical

care

delivery,

lack

of

opportunities

for

learning

and

skill

development,

unfair

salaries,

complex

nature

of

work,

and

unprofessional

practice.

A1.

Difficult

nature

of

critical

care

delivery

Critical

care

delivery

is

complex

and

difficult

because

patients

who

are

hospitalized

in

ICUs

usually

are

critically

ill

and

suffer

from

life-threatening

conditions.

The

participating

nurses

referred

to

low

nurse-patient

ratio

as

a

major

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management.

The

number

of

nurses

is

low

and

we

have

to

do

extra

working

shifts.

Therefore,

we

are

too

fatigued

to

provide

quality

care.

Or,

we

are

very

busy

at

work.

There

are

only

two

nurses

in

each

shift

and

hence,

we

have

not

adequate

time

for

implementing

care

measures

properly.

For

instance,

instead

of

letting

gavage

soup

pass

through

the

nasogastric

tube,

we

push

it

forcibly

by

using

a

gavage

syringe.

Another

instance

is

that

we

do

not

perform

suctioning

properly

in

order

to

be

able

to

carry

out

our

other

care-related

responsibilities

(P.

2).

Nursing

staff

shortage

negatively

affected

the

participants’

care

quality

through

increasing

their

workload

and

the

number

of

their

mandatory

extra

shifts.

Mandatory

extra

shift

was

referred

to

by

the

participants

as

another

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management.

Such

working

schedule

tired

them,

disturbed

their

personal

life,

broke

their

concentration,

and

reduced

the

quality

of

care.

As

I

have

a

little

baby,

I

don’t

want

to

do

extra

shifts.

However,

the

hospital

nursing

office

doesn’t

agree

and

thus,

I

have

to

do

extra

shifts.

When

doing

extra

shifts,

I’m

greatly

preoccupied

with

my

baby

and

hence,

I

cannot

perform

my

tasks

properly.

For

instance,

I

may

avoid

performing

suctioning

accurately

(P.

1).

Another

workforce-related

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management

was

lack

of

professional

physiotherapists

in

hospitals.

Therefore,

the

participants

were

required

to

do

the

extra

task

of

performing

physiotherapy

for

patients.

However,

they

considered

physiotherapy

neither

as

their

own

responsibilities

nor

as

a

routine

practice

and

hence,

it

was

usually

overlooked.

It

is

for

about

two

years

that

there

is

no

physiotherapist

in

our

hospital

and

thus,

physiotherapy

is

usually

performed

by

us

even

though

it

is

not

among

our

responsibilities.

We

perform

physiotherapy

only

for

the

sake

of

patients.

Of

course,

our

physiotherapies

are

not

standard

enough

(P.

3).

Critical

conditions

of

patients

who

are

hospitalized

in

ICUs

and

their

greater

need

for

specialized

care

services

along

with

serious

staff

shortage

had

dramatically

expanded

our

participants’

workload.

Such

a

working

condition

had

forced

them

to

pay

little

attention

to

the

quality

of

care.

On

the

other

hand,

during

shift

handover,

the

quantity

of

care

was

valued

much

greater

than

its

quality.

In

other

words,

if

nurses

performed

smaller

number

of

their

tasks

with

greater

quality,

they

were

accused

of

shirking.

Such

a

practice

had

resulted

in

the

delivery

of

low-quality

care.

When

I’m

too

busy,

I

cannot

perform

suctioning

or

other

care

measures

accurately

because

I

need

to

perform

each

measure

quickly

in

order

to

have

adequate

time

for

my

other

tasks.

Thus,

I

usually

pay

little

attention

to

the

quality

of

work

because

during

shift

handover,

no

one

values

the

quality

of

my

care;

rather,

they

only

value

the

amount

of

undone

tasks.

Therefore,

I

need

to

do

all

my

tasks

at

any

level

of

quality

in

order

not

to

be

accused

of

shirking

(P.

4).

Despite

the

necessity

to

use

high-tech

equipment

in

ICUs,

our

participants

noted

that

they

had

little

access

to

such

equipment.

They

referred

to

defective

or

inadequate

equipment

as

another

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management.

In

other

words,

they

had

many

difficulties

in

providing

quality

patient

care

due

to

having

limited

access

to

basic

critical

care

equipment.

Defective

equipment

resulted

in

providing

nonstandard

care

while

lack

of

equipment

resulted

in

failure

to

perform

some

care

measures

such

as

measuring

the

pressure

of

endotracheal

tube

cuff.

The

remote

controllers

of

the

beds

in

our

unit

are

defective.

When

we

are

too

busy

with

other

care

measures,

we

are

unable

to

change

the

controllers

and

thus,

patients

may

be

in

an

inaccurate

position

during

gavage

(P.

5).

We

never

measure

the

pressure

of

endotracheal

tube

cuff

because

we

have

no

access

to

the

necessary

equipment

(P.

7).

Another

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management

was

poor

and

nonstandard

structural

conditions

of

ICUs

both

for

patients

and

nurses.

For

instance,

the

participants’

working

unit

had

neither

an

air

conditioning

system

nor

an

isolated

room

for

patients

with

infectious

diseases.

Besides,

the

windows

to

open

space

were

kept

open

for

long

hours

and

inter-bed

distances

were

too

small.

Therefore,

the

likelihood

of

infection

transmission

was

high.

In

addition,

the

staff

resting

room

was

in

poor

condition.

The

physical

space

of

the

unit

is

too

awful.

There

is

a

small

space

between

the

beds

and

there

is

no

air

conditioning

system

in

the

unit.

In

case

of

poor

air

conditioning,

both

nurses

and

patients

are

at

risk

of

bacterial

infections

(P.

6).

A2.

Lack

of

opportunities

for

learning

and

skill

development

One

of

the

key

characteristics

of

critical

care

nurses

is

to

have

great

knowledge

of

care.

In

other

words,

nurses

who

are

not

knowledgeable

enough

cannot

work

in

these

units.

Nonetheless,

our

participants’

experiences

showed

that

critical

care

services

were

provided

based

on

usual

routines.

In

other

words,

novice

nurses

learned

the

way

of

care

delivery

from

their

experienced

colleagues

and

took

professional

knowledge-based

practice

for

granted.

Such

a

practice

had

resulted

in

nonstandard

care

delivery.

The

most

important

thing

for

us

is

that

the

endotracheal

tube

cuff

be

kept

full.

Therefore,

other

things

(such

as

the

pressure

of

the

cuff)

are

not

very

important.

We

just

inject

5

cc

of

air

into

the

cuff.

According

to

the

participants,

some

critical

care

nurses

did

not

have

enough

professional

competence

for

working

in

ICUs

due

to

poor

in-service

education.

For

instance,

some

nurses

were

not

skillful

enough

for

measuring

the

pressure

of

endotracheal

tube

cuff

or

doing

physiotherapy.

Moreover,

as

attending

physicians

or

anesthesiologist

refrained

from

setting

ventilators,

nurses

were

obliged

to

do

this

task

despite

having

received

no

in-depth

training

in

this

area.

Consequently,

they

set

ventilators

based

on

their

own

personal

experience.

I

have

no

adequate

knowledge

about

ventilators.

Thus,

there

may

be

an

opportunity

for

weaning

a

patient

from

the

ventilator

while

I

cannot

take

advantage

of

such

opportunity

due

to

having

poor

weaning

skills.

Therefore,

the

patient

may

unnecessarily

receive

mechanical

ventilation

for

many

days

(P.

8).

A3.

Unfair

salaries

Because

of

their

heavier

workload

and

stressful

work

condition,

the

participating

nurses

expected

to

receive

higher

salaries

compared

with

nurses

in

other

hospital

wards.

However,

hospital

administrators’

inattention

to

fair

budget

and

resource

allocation

had

reduced

their

motivation

for

work.

Financial

issues

were

so

important

to

the

nurses

that

they

referred

to

them

as

a

significant

factor

behind

care

quality.

The

salaries

of

critical

care

nurses

should

be

different

from

those

of

nurses

in

other

hospital

wards.

However,

there

is

no

difference

between

the

salaries

of

these

two

groups

in

our

hospital.

Sometimes,

critical

care

nurses’

salaries

are

even

less

than

other

nurses.

Such

practice

significantly

contributes

to

our

poor

motivation

for

work

(P.

1).

A4.

Complex

nature

of

work

When

providing

care

to

critically-ill

patients

in

critical

situations,

the

nurses

focused

mainly

on

saving

patients’

life

and

paid

little

attention,

if

any,

to

the

requirements

of

each

care-related

activity.

Accordingly,

they

might

insert

an

intra-tracheal

tube

or

perform

suctioning

under

unsterile

conditions,

resulting

in

greater

risk

for

VAP.

The

likelihood

of

such

an

unsterile

practice

was

greater

in

stressful

situations

such

as

in

emergencies

or

once

working

with

an

inexperienced

colleague.

When

a

patient

is

critically-ill

and

needs

intubation,

I

just

focus

on

intubating

him/her

irrespective

of

the

quality

or

the

sterility

of

the

procedure.

The

most

important

thing

in

such

situations

is

to

prevent

patient’s

death

(P.

9;

group

discussion).

Shortage

of

personal

protective

equipment

had

also

caused

most

of

the

participants

to

develop

hospital-acquired

respiratory

infections.

They

referred

to

this

fact

as

a

negative

experience

and

mentioned

that

they

avoid

providing

standard

care

to

patients

with

serious

infections

in

order

to

protect

themselves

against

infections.

Here,

I

developed

pneumonia

several

times.

In

order

to

prevent

another

episode

of

pneumonia,

I

perform

suctioning

for

patients

with

pneumonia

in

a

very

short

period

of

time.

Such

practice

reduces

the

quality

of

my

care

(P.

6).

A5.

Unprofessional

practice

Due

to

the

critical

conditions

of

patients

who

are

hospitalized

in

ICUs,

critical

care

nurses

need

to

have

high

levels

of

critical

care

specialty,

knowledge,

and

experience.

They

not

only

need

to

be

highly

knowledgeable,

but

also

should

properly

use

their

knowledge

in

their

practice.

Nonetheless,

nursing

staff

shortage

in

the

study

setting

had

resulted

in

the

recruitment

of

inexperienced

nurses

for

ICU.

Inexperienced

nurses

avoided

providing

care

services

independently

in

order

not

to

be

involved

in

malpractice

lawsuits.

I

avoid

weaning

a

patient

from

ventilator

independently

and

attempt

to

do

it

after

obtaining

my

senior

or

manager’s

permission.

I

usually

perform

what

they

recommend

(P.

8).

Some

of

the

participating

nurses

had

no

healthy

attitude

toward

quality

care

delivery

and

hence,

they

used

to

provide

care

based

on

their

own

beliefs

and

experience.

For

instance,

some

of

them

did

not

maintain

sterility

while

doing

nursing

procedures

and

believed

that

such

practice

is

sound.

When

I

go

from

one

patient

to

another,

I

simply

change

my

gloves

and

believe

that

it

is

enough

for

preventing

infections.

I

have

no

firm

belief

in

washing

hands

before

doing

procedures

(P.

9,

group

discussion).

B.

Poor

organizational

culture

Another

major

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management

was

poor

organizational

culture.

Organizational

culture

has

a

significant

effect

on

organizational

and

employee

performance.

Factors

such

as

supervision

and

control,

organizational

relations,

and

managerial

support

can

contribute

to

the

formation

of

cultural

norms.

B1.

Strict

supervision

of

nurses

Our

nurses

were

continuously

monitored

by

their

administrators.

However,

they

believed

that

evaluation

of

employee

performance

is

not

performed

effectively

because

administrators

who

did

evaluations

usually

focused

more

on

nursing

documentations

than

the

process

of

care

delivery

and

attempted

to

pinpoint

employees’

weaknesses

in

order

to

punish

them

instead

of

minimizing

shortages

and

weaknesses.

Some

of

the

participants

also

argued

that

administrators

usually

evaluate

each

nurse

based

on

their

own

previous

attitudes

towards

her/him.

Such

a

poor

evaluation

had

reduced

the

participants’

motivation

for

quality

care

delivery.

Previously,

they

recruited

many

novice

staff

to

the

unit

and

thus,

several

errors

happened

in

the

unit

and

all

of

us

were

punished

consequently.

Thereafter,

they

never

pay

attention

to

the

ICU

and

our

matron

believes

that

ICU

staff

never

perform

their

tasks

appropriately

(P.

10).

B2.

Poor

professional

interactions

The

ability

to

establish

effective

communications

with

colleagues

is

a

basic

clinical

skill

and

a

key

component

of

efficient

care

delivery

in

ICUs.

Nonetheless,

most

participants

referred

to

poor

inter-

and

intra-professional

interactions

as

another

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management.

Inter-professional

distrust

and

poor

interdisciplinary

collaboration

were

among

the

participants’

main

concerns.

In

the

study

setting,

physicians

had

no

trust

in

nurses

and

accused

them

of

shirking,

resulting

in

the

reduction

of

nurses’

motivation

for

quality

care

delivery.

Every

morning,

we

wash

and

rinse

patients’

mouth

with

chlorhexidine.

However,

when

attending

the

unit,

physicians

get

angry

and

complain

that

why

we

do

not

perform

mouth

washing

for

patients.

They

do

not

trust

us

when

we

say

that

we

have

done

mouth

washing.

Such

behaviors

of

physicians

make

us

unmotivated

(P.

5).

On

the

other

hand,

there

were

weak

intra-professional

interactions

among

nurses

due

to

their

heavy

workload.

In

other

words,

they

were

unable

to

help

each

other

in

doing

care-related

activities.

Sometimes,

the

nurses

were

even

unable

to

perform

their

activities

due

to

the

lack

of

help

and

support.

I

cannot

ask

my

colleagues

to

help

me

because

they

are

heavily

involved

with

their

own

duties.

If

they

help

me,

their

duties

would

remain

undone.

Therefore,

I

cannot

efficiently

perform

suctioning

when

I’m

alone

(P.

11).

B3.

Reluctance

to

perform

care

measures

Our

participants’

detailed

another

problem

in

managing

VAP

as

their

reluctance

and

lack

of

motivation

for

performing

care

measures.

Factors

contributing

to

such

reluctance

were,

but

not

limited

to,

inaccurate

judgments,

administrators’

inattention

to

nurses,

poor

accommodation

for

nurses,

and

similar

salaries

for

critical

care

nurses

and

the

nurses

of

other

hospital

wards.

Such

situations

disappointed

the

participants

and

hence,

they

had

no

motivation

for

better

care

delivery.

Our

resting

room

is

of

poor

condition.

No

one

values

our

welfare.

When

we

go

to

the

resting

room

to

take

some

rest,

such

problems

add

psychological

fatigue

to

our

physical

fatigue

because

we

feel

that

no

one

values

us

(P.

10).

B4.

Routine-based

practice

The

other

barrier

to

effective

VAP

management

was

nurses’

routine-based

practice

due

to

lack

of

efficient

incentive

systems

and

poor

workforce

development

policies.

According

to

the

participants,

their

administrators

paid

little

attention,

if

any,

to

their

career

advancement

and

professional

development,

did

not

encourage

them,

and

used

punishment

instead

of

encouragement.

Therefore,

the

nurses

were

reluctant

to

learn

and

provide

quality

care.

If

you

do

your

tasks

correctly,

our

administrators

never

encourage

you.

However,

if

you

commit

an

error,

they

will

punish

you.

The

predominant

system

in

our

setting

is

punishment

not

incentive

(P.

1).

The

purpose

of

the

study

was

to

explore

critical

care

nurses’

experiences

of

the

barriers

to

VAP

management.

The

study

findings

indicated

that

there

were

many

barriers

to

effective

VAP

management

in

ICUs.

One

of

the

major

barriers

to

VAP

management

was

nurses’

low

QWL.

Mullen

(2015)

also

noted

that

in

the

United

States,

nurses

face

many

barriers

in

their

working

life

(25).

Long

working

hours

due

to

mandatory

extra

shifts

was

among

the

factors

which

contributed

to

the

difficulty

of

critical

care

delivery,

nurses’

fatigue,

and

reduced

quality

of

nursing

care.

Olds

et

al

(2010)

also

reported

that

increased

work

hours

raise

the

likelihood

of

adverse

events

and

errors

in

healthcare

(26).

Renata

et

al.

(2012)

also

found

nurses’

heavy

workload

as

a

risk

factor

for

nosocomial

infections

(27).

Duffin

(2014)

noted

that

higher

nurse-bed

ratio

prolongs

patients’

survival

in

ICUs

(28).

The

results

of

studies

made

by

Laschinger

et

al.

(2000)

also

illustrated

that

putting

nurses

under

pressure

leaves

them

with

feelings

such

as

dissatisfaction,

frustration,

and

powerlessness

(29)

and

affects

their

QWL.

Our

findings

also

showed

that

lack

of

professional

physiotherapists

in

hospitals

results

in

added

responsibilities

for

nurses.

It

is

noteworthy

that

as

a

key

component

of

critical

care,

physiotherapy

is

of

paramount

importance

to

effective

airway

clearance

and

VAP

management

(30).

We

also

found

that

nonstandard

physical

structure

of

ICU

and

defects

or

shortages

of

high-tech

equipment

in

this

unit

reduced

care

quality

and

interfered

with

effective

care

delivery.

This

finding

is

in

line

with

the

findings

reported

by

Matakala

et

al.

(2014)

who

reported

that

the

design

of

ICU

can

affect

care

delivery,

outcomes

of

care,

and

the

incidence

of

infections

(31).

Another

finding

of

the

study

was

that

care

services

were

provided

based

on

old

routines.

Lack

of

opportunities

for

learning

and

skill

development

requires

nurses

to

deliver

care

services

more

based

on

old

routines

and

personal

experiences

than

clinical

standards

and

guidelines.

Studies

showed

that

the

nursing

care

delivery

system

in

Iran

is

congruent

with

the

attributes

of

Johnson’s

Delegated

Medical

Care

model.

In

this

model,

the

cornerstone

of

care

is

routine-based

practice

and

execution

of

medical

orders

(32).

Evidence

shows

that

one

of

the

key

prerequisites

to

effective

VAP

prevention,

particularly

in

countries

with

limited

resources,

is

continuing

education

of

healthcare

workers

(33,

34).

In

fact,

poor

in-service

training

would

result

in

nonstandard

care

delivery.

Study

findings

also

revealed

unfair

salaries

as

another

factor

affecting

nursing

care

delivery

and

VAP

management

in

ICUs.

Administrators’

indifference

toward

same

salaries

for

critical

care

nurses

and

nurses

working

in

other

hospital

wards

had

reduced

our

participants’

motivation

for

work

and

the

quality

of

their

care.

Unfair

payment

for

different

groups

of

hospital

staff

has

been

reported

as

a

significant

factor

behind

nurses’

poor

motivation

for

work

(35

and

36).

Unfulfilled

work-related

needs

of

nurses

(such

as

need

for

personal

protective

equipment)

had

faced

the

study

participants

with

serious

complications

such

as

pneumonia

and

thereby,

reduced

the

quality

of

their

care.

According

to

Stone

et

al.

(2004),

nurses’

working

condition

is

among

the

major

risk

factors

for

healthcare-related

infections

and

occupational

exposure

to

infections

(37).

Evidence

indicates

that

healthcare

workers

are

at

risk

for

developing

hospital-acquired

infections.

Moreover,

nurses’

safety

and

occupational

health

have

been

reported

to

be

correlated

with

their

job

satisfaction

(38).

Alex

(2011)

also

found

job

satisfaction

as

a

determining

factor

behind

hospital

staff’s

performance

and

the

quality

of

their

care

services

(39).

According

to

the

findings

of

the

present

study,

nurses’

disbelief

in

standard

care

delivery

was

another

main

factor

contributing

to

VAP

management.

Such

disbelief

can

result

in

arbitrary

care

delivery.

Studies

have

shown

a

significant

correlation

between

individuals’

attitudes

and

their

behavioral

pattern.

For

instance,

Noruzi

et

al.

(2015)

found

that

nurses’

personal

attitudes

and

beliefs

are

correlated

with

their

adherence

to

infection

prevention

standards

(40).

On

the

other

hand,

study

findings

revealed

that

nurses’

professional

experience

had

a

significant

role

in

VAP

management

and

standard

care

provision.

In

other

words,

nurses

with

limited

professional

experience

provided

lower

quality

care.

The

results

of

a

study

by

Jafari

et

al.

(2012)

illustrated

that

novice

nurses’

professional

competence

is

not

proportionate

to

the

requirements

of

clinical

settings

and

hence,

they

provide

low-quality

care

(41).

Vogus

et

al.

(2014)

also

reported

that

in

their

first

year

of

professional

practice,

novice

nurses’

performance

is

significantly

affected

by

environment,

workplace

conditions,

and

work-related

factors

(42).

Generally,

workplace

culture

and

atmosphere

can

dramatically

affect

ward

outcomes

such

as

staff

performance

(43).

We

also

found

that

factors

such

as

strict

supervision

of

nurses

and

inappropriate

evaluation

of

employee

performance

reduced

the

nurses’

motivation

for

work,

gave

them

a

negative

attitude

towards

their

administrators,

and

prevented

them

from

correcting

their

errors.

The

administrators

of

the

study

settings

paid

little

attention

to

the

quality

of

care

and

focused

mainly

on

spotting

employees’

errors

and

punishing

them.

According

to

the

Social

Contracts

Theory,

nurses

who

feel

injustice

in

performance

evaluation,

experience

some

kind

of

negative

tension

and

attempt

to

reduce

their

involvement

in

the

organization’s

affairs

in

order

to

relieve

their

tension.

On

the

other

hand,

nurses

who

feel

that

performance

evaluation

is

performed

fairly

become

motivated

to

play

a

more

significant

role

in

their

organizations

(44).

The

study

findings

also

indicated

that

poor

professional

interactions

(such

as

inter-professional

distrust)

reduced

the

quality

of

VAP-related

care

services.

Moreover,

nurses’

heavy

workload

had

undermined

their

ability

to

closely

collaborate

with

each

other.

Havens

(2010)

reported

that

improving

nurses’

relationships

with

other

healthcare

professionals

can

lower

the

rate

of

nosocomial

infections

and

improve

the

quality

of

care

(45).

Two

other

significant

factors

behind

ineffective

VAP

management

in

the

study

setting

were

routine-based

practice

and

lack

of

innovation

at

work

due

to

administrators’

inattention

to

personnel

and

the

dominance

of

punishment

system.

These

findings

are

contrary

to

the

findings

reported

by

Sajadi

et

al.

(2011)

who

found

no

significant

correlation

between

nurses’

creativity

and

organizational

culture

(46).

This

contradiction

may

be

due

to

differences

in

the

design

and

the

setting

of

these

two

studies.

This

study

was

done

in

a

single

ICU

setting

and

thus,

the

findings

may

have

limited

generalizability.

Therefore,

conducting

further

studies

in

different

settings

is

recommended

in

order

to

identify

other

barriers

to

effective

VAP

management.

Poor

structural

and

process

standards

as

well

as

poor

organizational

culture

are

the

major

barriers

to

effective

VAP

management.

The

findings

of

the

present

study

enhanced

our

understanding

of

the

fact

that

administrators

need

to

adopt

strategies

to

improve

nurses’

welfare

and

motivation,

alleviate

their

problems,

boost

their

salaries,

enhance

the

quality

of

performance

supervision

and

evaluation,

and

recruit

more

nurses

into

ICUs.

On

the

other

hand,

nurses

need

to

learn

new

and

standard

approaches

to

care

delivery

in

order

to

play

a

more

significant

role

in

VAP

management.

Future

studies

are

recommended

to

develop

and

implement

strategies

to

improve

organizational

cultures

and

nurses’

QWL

as

well

as

to

change

nurses’

personal

beliefs

and

attitudes.

Acknowledgement

This

study

was

part

of

a

Master’s

thesis

in

Critical

Care

Nursing.

The

authors

are

grateful

to

all

participants

of

the

study

who

shared

their

experiences

and

the

Research

Administration

of

Lorestan

University

of

Medical

Sciences

which

approved

and

funded

the

study.

Guénou

M.

Prevalence

of

nosocomial

infections

and

anti-infective

therapy

in

Benin:

results

of

the

first

nationwide

survey

in

2012.

ARIC

2014;

3(17):

1-6.

doi:

10.1186/2047-2994-3-17

2.

Morgan

D,

Lomotan

L,

Agnes

K,

Grail

L,

Roghmann

M.

Characteristics

of

healthcare-associated

infections

contributing

to

unexpected

in-hospital

deaths.

Infect

Control

Hosp

Epidemiol

2010;

31(8):

864–866.

doi:

10.1086/655018

3.

Harris

A,

Pineles

L,

Belton

B,

Johnson

K,

Shardell

M,

Loeb

M,

et

al.

Universal

glove

and

gown

use

and

acquisition

of

antibiotic

resistant

bacteria

in

the

ICU:

a

randomized

trial.

JAMA

2013;

310(15):

1571-1580.

doi:

10.1001

4.

Bagheri

M,

Amiri

M.

Nurse’s

knowledge

of

evidence-

based

guidelines

for

preventing

ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

in

intensive

care

units.

JNMS

2014;

1(1):

44-48.

URL

http://jnms.mazums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-327-1&slc_lang=en&sid=1

5.

Kalanuria

A,

Zai

W,

Mirski

M.

Ventilator-associated

pneumonia

in

the

ICU.

Crit

Care

Med

2014;

18(208):

1-8.

doi:

10.1186/cc13775

6.

Sharma

S,

Kaur

J.

Randomized

control

trial

on

efficacy

of

chlorhexidine

mouth

care

in

prevention

of

ventilator-

associated

pneumonia.

NMRJ

2012;

8(2):

169-

178.

7.

Gadani

H,

Vyas

A,

Kar

AK.

A

study

of

ventilator-associated

pneumonia:

Incidence,

outcome,

risk

factors

and

measures

to

be

taken

for

prevention.

Indian

J

Anaesth.

2010;

54(6):535-40.

doi:

10.4103/0019-5049.72643.

8.

Darvishi

Khezri

H.

The

role

of

oral

care

in

prevention

of

ventilator

associated

pneumonia:

A

literature

Review.

JSSU

2014;

21(6):

840-849.

http://jssu.ssu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-1499-1&slc_lang=en&sid=1

9.

Behesht

Aeen

F,

Zolfaghari

M,

Asadi

Noghabi

AA.

Nurses’

performance

in

prevention

of

ventilator

associated

pneumonia.

Hayat

2013;

19(3):

17-27.

http://hayat.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-26-3&slc_lang=en&sid=1

10.

Bonsal

Cooper

V,

Haut

C.

Preventing

ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

in

children:

an

evidence-based

protocol.

Critical

Care

Nurse

2013;

33(3):

29-21.

doi:

10.4037/ccn2013204

11.

Rello

J,

Lode

H,

Cornaglia

G,

Masterton

R.

A

European

care

bundle

for

prevention

of

ventilator-associated

pneumonia.

Intensive

care

med

2010;

36(5):

773-780.

doi:

10.1007/s00134-010-1841-5

12.

Aminzadeh

Z,

Hajiekhani

B.

Bacterial

endotracheal

tube

colonization

in

intubated

patients

in

poisoning

ICU

ward

of

Loghman

Hakim

hospital

of

Tehran

in

2005.

Horizon

Med

Sci.

2007;

13

(2):12-19.

http://hms.gmu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-1-56&slc_lang=en&sid=1

13.

Salehifar

E,

Abed

S,

Mirzaei

E,

Kalhor

S,

Eslami

G,

Ala

S,

et

al

.

Evaluation

of

profile

of

Microorganisms

involved

in

hospital-acquired

infections

and

their

antimicrobial

resistance

pattern

in

intensive

care

units

of

Emam

Khomeini

hospital,

Sari,

2011-2012.

J

Mazandaran

Univ

Med

Sci.

2013;

22

(1):151-162.

http://jmums.mazums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-29-90&slc_lang=en&sid=1

14.

Lawrence

P,

Fulbrook

P.

The

ventilator

care

bundle

and

its

impact

on

ventilator-

associated

pneumonia:

a

review

of

the

evidence.

BACCN

2011;

16(5):

222-234.

doi:

10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00430.x.

15.

Mousavi

S,

Hasibi

M,

Mokhtari

Z,

Shaham

G.

Evaluation

of

safety

standards

in

operating

rooms

of

Tehran

University

of

Medical

Sciences(TUMS)

Hospitals

in

2010.

PAYAVARD

2011;

5(2):

10-17.

http://payavard.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-25-73&slc_lang=en&sid=1

16.

Mari

N,

Udilja

kN,

Karaula

NT,

Jurina

H,

Makovi

M,

Beki

D.

The

impact

of

interventions

to

improve

adherence

to

preventive

measures

on

the

incidence

of

nosocomial

infections

in

ICUs.

SIGNA

VITAE

2014;

9

(1):

34

–

37.

17.

Lambert

M,

Palomar

M,

Agodi

A,

Hiesmyr

M,

Lepape

A,

Ingenbleek

A.

prevention

of

ventilator-associated

pneumonia

in

intensive

care

units:

an

international

online

survey.

ARIC

2013;

2(9):

1-8.

doi:

10.1186/2047-2994-2-9

18.

Morris

A,

Everingham

K,

Culloch

C,

Nulty

J,

Brooks

O,

Swann

D.

Reducing

ventilator-

associated

pneumonia

in

intensive

care:

impact

of

implementing

a

care

bundle.

Crit

Care

Med

2011;

39(10):

2218-2224.

doi:

10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182227d52

19.

Salimi

s,

Anami

I,

Noroznia

SH.

Rastad

M,

Acdemir

N.

Effect

Of

Standardization

Of

Nursing

Cares

On

Incidence

Of

Nosocomial

Infection

In

Micu.

Urmia

Medical

Journal

2009;

19(4):

310-315.

http://umj.umsu.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-3-40&slc_lang=en&sid=1

20.

Jain

M,

Miller

L,

Belt

D,

King

D,

Berwick

M.

Decline

in

ICU

adverse

events

/

nosocomial

infections

and

cost

through

a

quality

improvement

initiative

focusing

on

teamwork

and

culture

change.

Qual

Saf

Health

Care

2006;

15(4):

235-239.

doi:

10.1136/qshc.2005.016576

21.

Graneheim

UH,

Lundman

B.

Qualitative

content

analysis

in

nursing

research:

concepts,

procedures

and

measures

to

achieve

trustworthiness.

Nurse

education

today.

2004;

24(2):105-12.

doi:

10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

22.

Carpenter

D,

Streubert

H,

Speziale

S.

Qualitative

research

in

nursing:

Advancing

the

humanistic

imperative.

Philadelphia:

Lippincott

Williams

and

Wilkins.

2011.

23.

Baraz-Pordanjani

S,

Memarian

R,

Vanaki

Z.

Damaged

professional

identity

as

a

barrier

to

Iranian

nursing

students’

clinical

learning:

a

qualitative

study.

Journal

of

Clinical