|

The effect of Hypertonic

Dextrose injection on the control of pain associated

with knee osteoarthritis

Mahshid Ghasemi (1)

Faranak Behnaz (2)

Mohammadreza Minator Sajjadi (3)

Reza Zandi (4)

Masoud Hashemi (5)

(1) Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology,

Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences,

Tehran, Iran

(2) Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology, Shohada

hospital, Shahid Beheshti University, Tehran,

Iran

(3) Orthopaedic surgeon, Taleghani Hospital

Research Development unit, Saheed Beheshti University

of medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

(4) M.D .Assistant Professor of Orthopedic Department,

Shahid Beheshti University of medical sciences,

Taleghani hospital, Tehran, Iran

(5) Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Shahid

Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Akhtar

hospital, Tehran, Iran

Correspondence:

Masoud Hashemi

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology, Shahid

Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Akhtar

hospital, Tehran, Iran

Email: dr.hashemi@sbmu.ac.ir

|

Abstract

Introduction: The

purpose of this study was to evaluate

the effect of dextrose injection on controlling

pain associated with knee osteoarthritis.

Methods: To

achieve the research objectives, available

sampling was done using 80 patients with

knee osteoarthritis referring to Taleghani

Hospital in 2017 and samples were divided

into two groups: 15% dextrose injection

and 25% hypertonic dextrose injection.

This injection was performed at the beginning

of the study, the first week, the fifth

week and the ninth week. During these

weeks, participants were asked to complete

the WOMAC questionnaire implementing the

VAS scale. After data collection, independent

t-test and two-way variance analysis with

repeated measures were used.

Findings: The findings showed that

15% and 25% dextrose injection had a significant

effect on the visual scale of pain and

function of patients, so that, during

weekly treatment, scales showed improvement

in treatment in these patients. Also,

other findings showed that injection of

25% dextrose had a significant visual

analog of patient’s pain and function

compared to 15%.

Conclusion:

In general, it can be suggested that the

use of dextrose prolotherapy is a simple,

safe, inexpensive, accessible and less

complicated method than other treatments

in these patients.

Key words:

Osteoarthritis, Prolotherapy, Treatment,

Health.

|

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common joint

disease in humans and is characterized by the

degradation of the hyaline cartilage and can

lead to chronic pain and severe disability in

the patient (1). The morning and the decrease

in the movement range of the joint are important

characteristics of this disease (2). The greatest

risk factor for this disease is age (3), but

high blood pressure, severe strokes, excessive

use of the joint, inoperative anterior cruciate

ligament and damage to the meniscus can also

result in knee OA (4-5). OA levels in all societies

are rising due to increased longevity. Pain,

stiffness and knee pain during active knee movements

are common symptoms of OA, which not only reduces

the ability of patients, but also adversely

affects the quality of life of patients (6).

Osteoarthritis is one of the five main causes

of physical disability in the elderly (1, 7).

It is estimated that 90% of people over 40 in

the United States suffer from osteoarthritis

(8). Studies show that the prevalence of knee

osteoarthritis is 60 to 90% as a cause of musculoskeletal

pain among people 65 years of age or older (9).

By 2020, it is estimated approximately 4.55

million Americans, i.e. 18.2% of the US population

will have osteoarthritis (10). According to

the World Health Organization, the prevalence

of osteoarthritis in the Iranian urban population

is reported to be about 19.3% (5). The findings

of a similar study in Iran show that osteoarthritis

is higher in the Iranian population than in

the other studied populations, and the prevalence

in women is more than in men (11). OA costs

60 billion dollars a year for the US economy

(12). This disease is one of the main causes

of functional impairment and has greatly influenced

people’s lives, including their mobility,

independence, and daily activities, resulting

in limited recreational activities, sports,

and work (13). The results of a 2004 study in

Iran investigating 200 patients with osteoarthritis

showed that high BMI, high age, and live in

a village were the main factors affecting the

inability of these patients (14). Sex also plays

a major role in this issue, about 2.3% to 3.4%

of the knee OA patients are female (15).

The inflammation process also plays an important

role in osteoarthritis, and cytokines such as

IL-1 beta, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor, and

IL-15 play a role in this disease (16-17). The

disease is divided into two primary and secondary

forms. In the primary type, the degeneration

process and joint destruction occurs without

previous anomalies. Its main cause is unknown,

usually it is seen in individuals over 40 years

of age with slow progressive and multiple arthroplasty,

and is seen through normal or abnormal pressure

on the weak joint (8, 15). Secondary osteoarthritis

is followed by an underlying cause such as fractures,

bone and joint injuries, infections, rheumatoid

arthritis, and congenital and metabolic diseases

(18).

In terms of pathology, this disease is caused

by three biological, mechanical and biomechanical

causes. Symptoms begin with mild pain in one

or more joints and gradually intensify. This

pain is improved with exertion and relaxation,

with the advancement of pain, it develops and

joint stiffness lasts for a few minutes (19).

Failure to use a joint with OA due to pain results

in rapid atrophy of the muscles around the joint,

and therefore, lead to muscle loss, which is

one of the most important factors for joint

support. Eventually, in the last stages of the

disease or when there is severe pain (20), it

disturbs patients’ quality of life, and

ultimately leads to surgery such as joint replacement

(21). Pain is a multidimensional phenomenon

that has physical, psychological, social, and

spiritual components, and is, in fact, a kind

of unpleasant sensory and psychological experience

that is associated with actual or potential

tissue damage and it is expressed with a series

of words from people who experience it (22).

The lack of management of chronic pain affects

the physical and mental condition of individuals,

decreases their quality of life and that of

their families, and on the other hand, along

with the physical and psychological disabilities,

it imposes a significant cost to the economic

resources of countries, health systems and insurance

(23). In addition to the direct medical costs

caused by pain, it imposes the following indirect

costs, such as complications of therapeutic

measures, the number of days someone cannot

handle, movement restrictions, being useless

and ineffective, functional disorders, pain-related

disabilities, and compensation for these disabilities

on the individual and the community (24).

In industrialized countries and developing

countries attention to knee osteoarthritis is

an important cause of pain and disability, the

loss of proper joint performance, and joint

instability and deformity are increasing (25).

Therefore, several therapeutic approaches have

been proposed for the treatment or improvement

of this disease. Multiple treatments for this

disease include medication, lifestyle changes,

weight loss, muscle strengthening, using cane,

brace, heel wedge and surgical procedures. All

of these methods have a sedative effect and

only delay the onset of the disease (26). The

standard of care and treatment is multifactorial

in osteoarthritis, and often involves physical

therapy, prescribing and taking anti-inflammatory

drugs, intracranial injection of hyaluronic

acid (visco-supplementation) and arthroscopic

surgery. New studies also show no therapeutic

effect left alone (27).

Unfortunately, no definitive treatment for this

disease has been found despite the many used

therapeutic methods. Therefore, given the long

duration, high financial costs, widespread side

effects, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,

and finally, the symptoms of the disease lead

to limitation of movement and severe disability

and loss of muscle performance and muscle weakness;

therapeutic goals of the disease should include

reducing pain and weakness, improving performance

and range of motion, and facilitating day-to-day

activities. Treatment of the disease includes

medical treatments and non-pharmacological treatments

including physiotherapy. Another promising treatment

that has recently been used to treat musculoskeletal

pain is prolotherapy (28, 29). Prolotherapy

is a selective therapeutic and complementary

injection for chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Prolotherapy techniques and injected intra-articular

materials are very different and are related

to the patient’s condition, severity of

symptoms and clinical manifestations of patients.

Prolotherapy involves infusion of a very small

amount of an anti-inflammatory or sclerosis

agent into the tendon, inflamed or painful joint

or ligament (30).

It is assumed that prolotherapy leads to stimulate

recovery in chronic soft tissue injuries; typically,

dextrose hypertonic is used in prolotherapy

for intramuscular injection (30). The study

of Reeves et al. (2003) showed that the pain

of the patients was significantly decreased

after the injection of into the hip (31). Jo

et al. also found that intra-joint 15% dextrose

injection can reduce knee pain in these individuals

(32). A study by Rabago et al showed that in

adults with osteoarthritis, using intra-articular

dextrose reduces pain, rigidity and increased

function of patients without side effects (33).

Knee osteoarthritis can result in severe physical

and mental disability, and the therapeutic goals

in this disease include reducing weakness, improving

performance, reducing pain, increasing the range

of motion, reducing the morning stiffness of

the joints, and facilitating the daily functioning

of life (34) and due to the need to find safe,

simple and inexpensive non-surgical treatments

to reduce pain and improve the function of patients

with knee osteoarthritis and the limited number

of studies in this field, this study aimed to

investigate the effect of dextrose injection

on the control of pain associated with knee

osteoarthritis in patients referred to Taleghani

Hospital (2017).

The study was a single-blind clinical trial.

The research population was all patients with

knee osteoarthritis, who were selected by available

sampling method from 80 knee osteoarthritis

patients referred to Taleghani Hospital. They

were randomly divided into two groups: 15% dextrose

injection and injection of hypertonic dextrose

25% divided. The sample size was 80 individuals

based on similar research (p0.05) and a test

power of 80%. The criteria for entering the

study included: unilateral idiopathic OA of

the knee, age range of 45-75 years, walking

ability, local knee pain with a score of more

than 5 based on VAS criteria and exit criteria

including: other knee diseases, hip joint OA,

and ankle sprain, radicular pain due to lumbar

spine disorders, intraocular effusion, history

of physiotherapy and intra-articular injection

in the past 6 months, psycho-mental diseases,

knee necrotic tissue, infection and tissue in

the blood, neurological, sensory and motor disorders,

history of knee surgery and obesity. Ethical

Criteria of this study was approved by the ethics

committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical

Sciences.

Method of implementation

After diagnosis of the patient as an appropriate

case, education about the method of implementation

and the benefits and possible complications

of participating in the project, written consent

was taken from the patient. They were informed

about the necessity of regular referral for

follow up, but that it was not imposed. The

intervention was performed without the cost

to the patient. Before the intervention, a questionnaire

was filled out including patient’s demographic

information, such as: gender, age, occupation,

involved side (upper leg), history of previous

treatments, and history of underlying illness

and the duration of symptoms. In addition to

providing an educational brochure on how to

inject, the time for referrals to perform tests

and the next visit was presented face to face.

Regarding moral considerations, the patient

was assured that they could be excluded from

the study whenever they wished, and that their

failure to cooperate with the doctor and the

hospital would not affect their treatment and

all patient information would be kept confidential.

The injection procedure was performed in such

a way that the patient was placed in a supine

position and marked with a knee flexion of 10-15

degrees on the medial side of the knee, marking

the injection area, and then the injection site

was disinfected with Povidone iodine and the

injected area was anesthetized with 1 ml 1%

Lidocaine solution and using needle number 25-27

after aspiration and ensuring proper placement

of needle for intra-articular injection (35).

In the 25% dextrose group, solution was made

of 5 cc 50% dextrose and 5 cc 1% lidocaine.

Then, 6 cc of this 25% dextrose solution was

injected into the patient’s joint and injection

was performed with the inferomedial approach

(33). In the 15% dextrose group, solution was

made of 6.75 cc 50% dextrose and 4.5 cc of 1%

lidocaine and 11.25 cc of normal saline 0.9%.

Then, 0.5 cc of this solution was 15% dextrose

that was injected as subdermal with peppering

technique with needle number 25 in the bone

ligament. There were 15 injections for each

patient (33). This injection was performed at

the beginning of the study, the first week,

the fifth week and the ninth week. The completion

of the WOMAC questionnaire and the implementation

of the VAS scale were performed before the intervention,

and in the first week, the fifth week, the ninth

week and the thirteenth week. To measure the

variables, the Western Ontario and McMaster

Universities (WOMAC) index and the VAS Scale

(Visual Analogue Scale) were used as follows.

Visual Analogue Scale

The visual analogue scale (VAS) indicates the

pain of the patients in general. This scale

is plotted as a 10 cm line, and the degree of

pain is graded from zero to 10 cm. The zero

number does not show any pain, 1 to 3 mild pain,

4 to 6 moderate pain and 7 to 10 severe pain

[36]. The internal reliability of this tool

has been reported as 0.85 to 0.95 (37).

Functional questionnaire of WOMAC

The WOMAC functional questionnaire consists

of 24 questions, 5 questions regarding pain,

2 questions related to stiffness and 16 questions

regarding the performance of patients with osteoarthritis.

The score for each question varies from zero

to four. This criterion is scored from zero

to 96. If the patient has no problem, then,

the score is zero and if they have a maximum

problem, score will be 96. Validity and reliability

of this tool have been investigated by Ebrahimzadeh

et al. and has been validated in the Persian

language. Cronbach’s alpha was estimated

0.9 in Persian language (5).

In analyzing data, the mean, standard deviations,

frequencies, tables and charts were used to

categorize and summarize the collected data.

In the study of statistical pre-requisites,

the number of observations per distribution

was used to test the natural distribution of

the data using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Regarding the existence of statistical hypotheses,

independent t-test and two way-analysis of variance

with repeated measures (p0.05) and using the

Statistical package of version 22 were used.

The

participants

in

the

present

study

consisted

of

48

(60%)

women

and

32

(40%)

men.

The

age

range

of

patients

was

(45-75)

years

and

the

mean

age

was

64.3

years.

VAS

variable

The

results

of

Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test

showed

that

the

distribution

of

data

was

normal

(P>

0.05).

T-test

showed

that

there

was

no

significant

difference

in

VAS

scale

between

the

two

groups

before

intervention

(t=0.781,

p>

0.05).

Two-way

analysis

of

variance

(week

×

group)

of

3×2

was

used

to

analyze

the

data.

The

results

are

presented

in

Table

1.

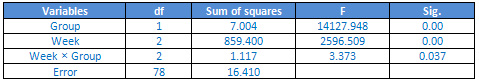

Table

1:

The

results

of

variance

analysis

of

VAS

scale

in

two

groups

The

findings

showed

that

the

main

effect

of

the

group

(F2.78

=

14127.948,

p<0/05),

the

main

effect

of

week

(F2.78

=

2596.509,

p<0.05)

and

the

interaction

between

the

group

and

the

week

was

significant.

The

significance

effect

of

the

group

means

that

there

is

a

significant

difference

between

the

two

groups

in

the

visual

analogue

scale.

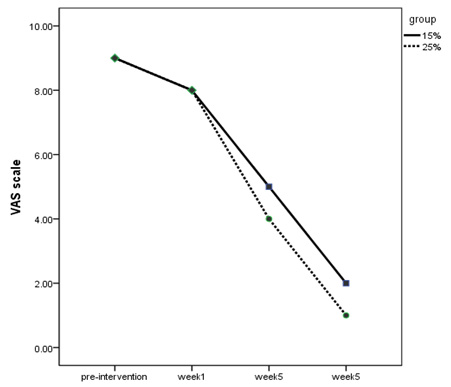

According

to

Chart

1,

the

group

of

25%

Dextrose

injection

experienced

more

pain

relief

than

the

15%

group.

Significance

of

the

weeks

of

treatment

meant

that

during

the

weeks

of

injection,

the

process

of

pain

reduction

continued

significantly

(Figure

1).

Figure

1:

VAS

scale

of

the

two

groups

in

the

weeks

of

treatment

WOMAC

variable

The

results

of

Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test

showed

that

the

distribution

of

data

was

normal

(P>0.05).

T-test

showed

that

there

was

no

significant

difference

in

the

WOMAC

scale

between

the

two

groups

before

the

intervention

(t

=

0.841,

p>0.05).

Two-way

analysis

of

variance

(week

×

group)

of

3×2

was

used

to

analyze

the

data.

The

results

are

presented

in

Table

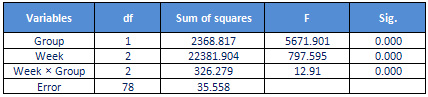

2.

Table

2:

The

results

of

variance

analysis

of

WOMAC

scale

in

two

groups

The

findings

showed

that

the

main

effect

of

the

group

(F2.78

=

5671/901,

p

<0.05),

the

main

effect

of

week

(F2.78

=

797/595,

p

<0.05)

and

the

interaction

between

the

group

and

the

week

was

significant.

The

significance

of

the

effect

of

the

group

means

that

there

is

a

significant

difference

between

the

two

groups

on

the

WOMAC

scale.

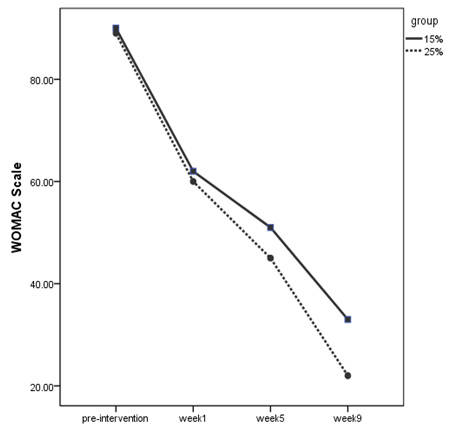

According

to

Figure

2,

it

can

be

said

that

25%

dextrose

injection

group

had

a

better

experience.

Significantly,

the

weeks

of

treatment

means

that

during

the

weeks

of

injection,

the

improvement

in

performance

was

significantly

increased

(Figure.

2).

Figure

2:

WOMAC

scale

of

the

two

groups

in

the

weeks

of

treatment

The

purpose

of

this

study

was

to

investigate

the

effect

of

dextrose

injection

on

pain

control

associated

with

knee

osteoarthritis.

The

findings

showed

that

injection

of

15%

and

25%

of

dextrose

had

a

significant

effect

on

the

visual

scale

of

pain

and

function

of

patients

so

that

during

treatment,

scales

showed

improvement

in

treatment

in

these

patients.

Also,

other

findings

showed

that

injection

of

25%

dextrose

compared

to

15%

had

a

significant

effect

on

visual

scale

of

pain

and

function

of

patients.

These

findings

are

consistent

with

the

results

of

Reeves

and

Hassanin

(2004),

Rabago

(2012),

Jo

(2004),

Reeves

and

Hassanin

(2000),

Hashemi

(2015)

and

Reeves

(2003).

For

example,

the

findings

of

Rabago

(2012)

showed

that

in

adults

with

osteoarthritis,

using

intra-arterial

dextrose

reduces

pain,

stiffness

and

increased

function

of

the

patients

without

any

side

effects

(33).

Joe

et

al.

(2004)

showed

that

the

pain

of

patients

was

significantly

reduced

by

15%

dextrose

injection.

They

also

concluded

that

intra-articular

injection

of

15%

dextrose

can

reduce

knee

pain

in

these

individuals

(32).

In

another

study,

Hashemi

et

al.

(2015)

attempted

to

compare

the

effect

of

ozone

therapy

and

dextrose

injection

in

patients

with

osteoarthritis.

They

evaluated

the

patients

using

the

WOMAC

and

VAS

scales.

The

findings

showed

that

in

both

groups,

pain

significantly

decreased

and

function

was

significantly

increased.

They

concluded

that

both

treatments

were

effective

in

reducing

pain

and

increasing

the

function

of

patients

(38).

In

subsequent

studies,

Reeves

and

Hassanein

(2000)

evaluated

the

effect

of

10%

dextrose

on

osteoarthritis

of

fingers.

After

six

months

of

follow

up,

they

found

that

in

the

dextrose

group,

a

significant

improvement

was

observed

in

the

case

of

xylocaine

group

during

fingers

movement

and

joint

flexion,

but

there

was

no

significant

improvement

in

pain

during

rest

and

recovery.

Another

study

on

knee

osteoarthritis

and

anterior

AC

ligation

showed

significant

improvement

in

pain

and

knee

swelling

and

flexion,

but

in

the

ACL

group,

there

was

no

significant

improvement

in

instability

(40).

Also,

Hassanein

and

Reeves

(2002)

conducted

a

study

on

patients

with

joint

instability

associated

with

ACL

rupture.

Their

findings

showed

that

in

patients

with

a

three

year

follow

up,

there

was

a

significant

decrease

in

pain

during

walking,

joint

swelling

and

joint

flexion

(40).

In

another

study

for

the

treatment

of

osteoarthritis,

finger

joints

used

10%

dextrose

over

two

months,

which

was

associated

with

beneficial

therapeutic

effects

(41).

In

another

study,

it

has

been

reported

that

in

third

world

countries

where

knee

insertion

surgery

is

not

available,

in

contrast

to

symptomatic

patients,

exercise,

physiotherapy

or

NSAIDs

are

prescribed.

The

researchers

found

that

10%

dextrose

could

modify

ACL

ligament

laxity,

which

was

not

associated

with

rupture,

and

also

prevented

gradual

salivation

after

surgery

in

joints

with

a

potential

displacement

(42).

The

mechanism

of

dextrose

effect

is

that

injection

of

a

stimulant

such

as

dextrose

into

a

damaged

joint,

possibly

with

local

inflammatory

reactions,

may

lead

to

an

increase

in

blood

flow

around

the

joint

and

damaged

tissue,

thereby

causing

self-repair

in

that

area.

The

dextrose

effect

has

another

mechanism

of

effect

(43).

They

showed

that

in

treatment

with

10%

Dextrose,

the

response

rate,

the

accumulation

and

tightening

of

the

uterus,

was

significantly

better

than

oxytocin

treatment

(40

units

per

liter).

These

researchers

argued

that

the

mechanism

of

dextrose

effect

is

that

since

the

activity

of

the

sympathetic

nervous

system

and

the

level

of

adrenalin

of

the

blood

increases

at

an

advanced

age,

this

increase

in

adrenalin

increases

the

level

of

cAMP

by

binding

to

beta

receptors

and

thus,

activates

the

protein

kina

dependent

to

cAMP,

which

in

turn

has

a

moderating

role

in

kinase

adhesion

to

the

myosin-like

chain

and

calcium-calmodulin

molecule,

and

therefore,

result

in

reduction

in

the

contractile

power

of

the

smooth

muscle.

Hence,

at

an

advanced

age,

it

is

necessary

to

increase

the

level

of

dextrose

and

consequently

increase

the

level

of

ATP

for

exposure

to

high

levels

of

catecholamines

to

help

accumulate

and

tighten

the

uterus.

According

to

the

results,

it

can

be

concluded

that

the

mechanism

of

the

effect

of

Dextrose

Prolotherapy

is

direct

effects,

osmotic

and

inflammatory

growth.

Dextrose

injection

with

a

concentration

of

less

than

10%

directly

promotes

cell

and

tissue

proliferation

without

inflammatory

reaction

and

a

high

concentration

of

10%

results

in

an

extracellular

osmotic

gradient

at

the

injection

site

resulting

in

loss

of

intracellular

and

lyse

cellular

cells

and

invasion

of

growth

factors

and

inflammatory

cells

that

start

the

wound

healing

cascade

in

that

particular

area.

Dextrose

is

an

ideal

proliferrant

because

it

is

water-soluble

and

is

a

mixture

of

blood

that

can

be

safely

injected

into

several

areas

and

in

large

quantities,

and

the

final

result

is

the

insertion

of

new

collagen

into

damaged

tissues

such

as

Ligaments

and

tendons.

When

extracellular

dextrose

concentrations

reach

5%,

normal

cells

begin

to

proliferate

and

produce

a

number

of

growth

factors

such

as

platelet

growth

factor,

TGF-,

epidermal

growth

factor,

basal

growth

factor

fibroblast

growth

factor,

insulin-like

growth

factor,

and

connective

tissue

growth

factor

that

repairs

the

tendon,

ligaments

and

other

soft

tissues.

Finally,

according

to

human

and

animal

studies,

dextrose

Prolotherapy

has

a

significant

effect

on

musculoskeletal

pain,

disability

and

cost

of

treatment.

Major

complications

from

dextrose

have

not

been

reported,

and

include

mostly

side

effects

of

injection

(pain

in

injection

site,

hematoma,

infection,

and

skin

pigmentation)

(38,

39).

According

to

the

findings

of

this

study,

the

use

of

Dextrose

Prolotherapy

is

a

simple,

safe,

inexpensive,

available

and

uncomplicated

method

for

other

remedies

in

these

patients,

which

has

been

confirmed

by

other

studies.

1.

Jordan

JM,

et

al.

The

impact

of

arthritis

in

rural

populations.

Arthritis

&

Rheumatism.

1995;

8(4):

242-250.

2.

Gordon,

A.,

P.,

the

Five

Pillars

of

Pain

Management:

A

Systematic

Approach

to

Treating

Osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis

and

Cartilage,

2006.

14:

p.

S193.

3.

Kurtai,

Y.,

et

al.,

Reliability,

construct

validity

and

measurement

potential

of

the

ICF

comprehensive

core

set

for

osteoarthritis.

BMC

musculoskeletal

disorders,

2011.

12(1):

p.

255.

4.

Buckwalter,

J.A.

and

N.E.

Lane,

Athletics

and

osteoarthritis.

The

American

Journal

of

Sports

Medicine,

1997.

25(6):

p.

873-881.

5.

Ebrahimzadeh,

M.H.,

et

al.,

The

Western

Ontario

and

McMaster

Universities

Osteoarthritis

Index

(WOMAC)

in

Persian

Speaking

Patients

with

Knee

Osteoarthritis.

Archives

of

bone

and

joint

surgery,

2014.

2(1):

p.

57.

6.

Neogi,

T.,

et

al.,

Association

between

radiographic

features

of

knee

osteoarthritis

and

pain:

results

from

two

cohort

studies.

Bmj,

2009.

339.

7.

Felson,

D.T.,

et

al.,

Osteoarthritis:

new

insights.

Part

1:

the

disease

and

its

risk

factors.

Annals

of

internal

medicine,

2000.

133(8):

p.

635-646.

8.

Sowers,

M.,

Epidemiology

of

risk

factors

for

osteoarthritis:

systemic

factors.

Current

opinion

in

rheumatology,

2001.

13(5):

p.

447-451.

9.

Williams,

F.M.

and

T.D.

Spector,

Biomarkers

in

osteoarthritis.

Arthritis

Research

and

Therapy,

2008.

10(1):

p.

10.

10.

Issa,

S.N.

and

L.

Sharma,

Epidemiology

of

osteoarthritis:

an

update.

Current

rheumatology

reports,

2006.

8(1):

p.

7-15.

11.

Haq,

S.A.

and

F.

Davatchi,

Osteoarthritis

of

the

knees

in

the

COPCORD

world.

International

journal

of

rheumatic

diseases,

2011.

14(2):

p.

122-129.

12.

Buckwalter,

J.A.,

C.

Saltzman,

and

T.

Brown,

The

impact

of

osteoarthritis:

implications

for

research.

Clinical

orthopaedics

and

related

research,

2004.

427:

p.

S6-S15.

13.

Salavati,

M.,

et

al.,

Validation

of

a

Persian-version

of

Knee

injury

and

Osteoarthritis

Outcome

Score

(KOOS)

in

Iranians

with

knee

injuries.

Osteoarthritis

and

Cartilage,

2008.

16(10):

p.

1178-1182.

14.

Shakibi,

M.R.,

Relationship

Between

Pain

and

Disability

in

Osteoarthritis

Patients:

Is

Pain

a

Predictor

for

Disability?

J.

Med.

Sci,

2004.

4(2):

p.

115-119.

15.

Moskowitz,

R.W.,

Osteoarthritis:

diagnosis

and

medical/surgical

management.

2001:

WB

Saunders

Company.

16.

Waldmann,

T.A.,

Targeting

the

interleukin-15

system

in

rheumatoid

arthritis.

Arthritis

&

Rheumatism,

2005.

52(9):

p.

2585-2588.

17.

Nishimoto,

N.,

et

al.,

Treatment

of

rheumatoid

arthritis

with

humanized

anti–interleukin-6

receptor

antibody:

A

multicenter,

double-blind,

placebo-controlled

trial.

Arthritis

&

Rheumatism,

2004.

50(6):

p.

1761-1769.

18.

Cole,

B.J.

and

C.D.

Harner,

Degenerative

arthritis

of

the

knee

in

active

patients:

evaluation

and

management.

Journal

of

the

American

Academy

of

Orthopaedic

Surgeons,

1999.

7(6):

p.

389-402.

19.

Moskowitz,

R.W.,

Osteoarthritis:

diagnosis

and

medical/surgical

management.

2007:

Lippincott

Williams

&

Wilkins.

20.

Mease,

P.J.,

et

al.,

Pain

mechanisms

in

osteoarthritis:

understanding

the

role

of

central

pain

and

current

approaches

to

its

treatment.

The

Journal

of

rheumatology,

2011.

38(8):

p.

1546-1551.

21.

Bennell,

K.,

et

al.,

Efficacy

of

physiotherapy

management

of

knee

joint

osteoarthritis:

a

randomised,

double

blind,

placebo

controlled

trial.

Annals

of

the

Rheumatic

Diseases,

2005.

64(6):

p.

906-912.

22.

Pizzo,

P.A.

and

N.M.

Clark,

Alleviating

suffering

101–pain

relief

in

the

United

States.

N

Engl

J

Med,

2012.

366(3):

p.

197-199.

23.

Gran,

S.V.,

L.S.

Festvåg,

and

B.T.

Landmark,

‘Alone

with

my

pain–it

can’t

be

explained,

it

has

to

be

experienced’.

A

Norwegian

in-depth

interview

study

of

pain

in

nursing

home

residents.

International

journal

of

older

people

nursing,

2010.

5(1):

p.

25-33.

24.

Brennan,

F.,

D.B.

Carr,

and

M.

Cousins,

Pain

management:

a

fundamental

human

right.

Anesthesia

&

Analgesia,

2007.

105(1):

p.

205-221.

25.

Foley,

A.,

et

al.,

Does

hydrotherapy

improve

strength

and

physical

function

in

patients

with

osteoarthritis—a

randomised

controlled

trial

comparing

a

gym

based

and

a

hydrotherapy

based

strengthening

programme.

Annals

of

the

Rheumatic

Diseases,

2003.

62(12):

p.

1162-1167.

26.

Andreoli,

T.E.,

et

al.,

Andreoli

and

Carpenter’s

Cecil

essentials

of

medicine.

2010:

Elsevier

Health

Sciences.

27.

Samson,

D.J.,

et

al.,

Treatment

of

primary

and

secondary

osteoarthritis

of

the

knee.

Evid

Rep

Technol

Assess

(Full

Rep),

2007.

157(157):

p.

1-157.

28.

Hassan,

F.,

et

al.,

The

effectiveness

of

prolotherapy

in

treating

knee

osteoarthritis

in

adults:

a

systematic

review.

British

Medical

Bulletin,

2017.

122(1):

p.

91-108.

29.

Reeves,

K.D.

and

K.

Hassanein,

Randomized

prospective

double-blind

placebo-controlled

study

of

dextrose

prolotherapy

for

knee

osteoarthritis

with

or

without

ACL

laxity.

Alternative

therapies

in

health

and

medicine,

2000.

6(2):

p.

68.

30.

Rabago,

D.,

A.

Slattengren,

and

A.

Zgierska,

Prolotherapy

in

primary

care

practice.

Primary

Care:

Clinics

in

Office

Practice,

2010.

37(1):

p.

65-80.

31.

Reeves,

K.D.

and

K.M.

Hassanein,

Long

term

effects

of

dextrose

prolotherapy

for

anterior

cruciate

ligament

laxity.

Alternative

therapies

in

health

and

medicine,

2003.

9(3):

p.

58.

32.

Jo,

D.

and

M.

Kim,

The

effects

of

Prolotherapy

on

knee

joint

pain

due

to

ligament

laxity.

Journal

of

the

Korean

Pain

Society,

2004.

17(1):

p.

47-50.

33.

Rabago,

D.,

et

al.,

Hypertonic

dextrose

injections

(prolotherapy)

for

knee

osteoarthritis:

results

of

a

single-arm

uncontrolled

study

with

1-year

follow-up.

The

Journal

of

Alternative

and

Complementary

Medicine,

2012.

18(4):

p.

408-414.

34.

Ross,

S.M.,

Osteoarthritis

of

the

knee:

An

integrative

therapies

approach.

Holistic

nursing

practice,

2011.

25(6):

p.

327-331.

35.

Hashemi,

S.M.,

et

al.,

Intra-articular

hyaluronic

acid

injections

vs.

dextrose

prolotherapy

in

the

treatment

of

osteoarthritic

knee

pain.

Tehran

University

of

Medical

Sciences,

2012.

70(2).

36.

Jensen,

M.P.,

P.

Karoly,

and

S.

Braver,

The

measurement

of

clinical

pain

intensity:

a

comparison

of

six

methods.

Pain,

1986.

27(1):

p.

117-126.

37.

Mokkink,

L.B.,

et

al.,

Construct

validity

of

the

DynaPort®

KneeTest:

a

comparison

with

observations

of

physical

therapists.

Osteoarthritis

and

Cartilage,

2005.

13(8):

p.

738-743.

38.

Hashemi,

M.,

et

al.,

The

effects

of

prolotherapy

with

hypertonic

dextrose

versus

prolozone

(intraarticular

ozone)

in

patients

with

knee

osteoarthritis.

Anesthesiology

and

pain

medicine,

2015.

5(5).

39.

Hashemi,

SM.,

et

al.,

Intra-articular

hyaluronic

acid

injections

vs.

dextrose

prolotherapy

in

the

treatment

of

osteoarthritic

knee

pain.

Tehran

Univ

Med

J,

2012.

70(2).119-125

40.

Kim

SR,

Stitik

TP,

Foye

PM:

critical

review

of

prolotherapy

growth

factor-beta

and

basic

fibroblast

growth

factor.

J

Bone

for

osteoarthritis

A

physiatric

perspective

2004;

83:

379-

Joint

Sur.

1995;

77:

543-5439.

41.

Reeves

KD,

Hassanein

K.

Randomized

prospective

double-blind

placebo-controlled

study

of

dextrose

prolotherapy

for

knee

osteoarthritis

with

or

without

ACL

laxity.

Altern

Ther

Health

Med.

2000;

6(2):68-74,

77-80

42.

Reeves

KD,

Harris

AL.

Recurrent

dislocation

of

total

knee

prostheses

in

a

large

patient:

Case

report

of

dextrose

proliferant

use.

Arch

Phys

Med

Rehabil

1997;

78:1039.

43.

Rafiee,

M.R.,

Samimi,

M.,

Nouraldini,

M.,

&

Mousavi,

S.GH.A.

Comparison

of

the

effect

of

10%

dextrose

and

oxytocin

40

units

per

liter

on

uterine

contraction

after

cesarean

section.

Yafte,

2006,

8(1),

13-18

|