|

|

|

Review Paper

........................................................

Education and Training

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| November 2014

- Volume 12 Issue 9 |

|

Prevalence

of Eye and Vision Abnormalities among a Sample

of Children up to five years old who visit Primary

Health Care Centers in Baghdad Alresafa

Zainab Mudhfer

Nasser (1)

Sanaa Jafar Hamodi Alkaisi (2)

Najah K.M. AL-Quriashi (3)

(1) M. B. Ch. B Specialist Family Physician

in the Arab Board of Family Medicine, Baghdad,

Iraq.

(2) M.B.Ch.B, F.I.B.M.S.\F.M Associated Prof.

in Family and Community Medicine ,Senior Specialist

Family Physician, Supervisor in the Residency

Program of Arab Board of Family Medicine, Member

in the Executive Committee of Iraqi Family Physicians

Society (IFPS) . Baghdad, Iraq.

(3) M.B.Ch.B., FICS.(Oph.),H.Dip.Laser(Oph.).

Assistant Professor and Senior Specialist Ophthalmologist

in Aljrahaat Teaching Hospital for Specialized

Surgeries / Medical city, Supervisor in the

Postgraduate Board Residency Program of Ophthalmology.

Baghdad, Iraq.

Correspondence:

Dr.Sanaa Jafar Hamodi Alkaisi, M.B.Ch.B, F.I.B.M.S.\F.M

Associate Prof and Senior Specialist Family

Physician, Supervisor in the Residency Program

of Arab Board of Family Medicine, member in

the Executive Committee of Iraqi Family Physicians

Society (IFPS) . Baghdad, Iraq.

Email: drsanaaalkaisi@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Background : Vision

disorders are the fourth most common disability

of children and the leading cause of handicapping

conditions in childhood. Eye examination

and vision assessment are vital for the

detection of conditions that result in

blindness, signify serious systemic diseases

which may lead to problems with school

performance, or at worst, threaten the

child's life.

Objectives :

1.To

identify the prevalence of vision and

eye abnormalities in children up to five

years old attending two of primary health

care centers in Baghdad Al resafa.

2. To identify some risk factors associated

with vision and eye abnormalities in this

age group.

Subjects and methods: A

descriptive cross-sectional study was

conducted from November 2011 to March

2012 in two primary health care centers

in Baghdad Al resafa. The sampling was

a non-probability convenient sample of

(407) children, and all the eligible,

willing participants were subjected to

a self -structured close ended questionnaire

and were subjected to the following examinations

by the researcher alone (inspection of

all children's eyes and eyelids for any

abnormalities, red reflex examination,

corneal light reflex test, near fixation,

ocular motility test, cover test, visual

acuity test). Statistical Package for

Social Sciences version 18 was used for

data input and analysis.

Result: The

prevalence of eye and vision abnormalities

is 6.14% (95%CI 4.09% - 9.05%).The prevalence

of strabismus 4.4 %, abnormal visual acuity1.5%,

nystagmus 0.5%, congenital glaucoma 0.25%.

In this study sample the majority of children

with ocular abnormalities were from the

second and fifth years of life (p=0.008).

The sex was not significantly associated

with ocular abnormalities (p=0.512). Prematurity

was not significantly associated with

eye problems (p>0.05). Low birth weight

was significantly associated with eye

problems (p=0.003). Family history of

congenital glaucoma, eye deviation, wearing

glasses during childhood, all were significantly

associated with eye problems (p=0.001),

but family history of nystagmus and cataract

was not significant (p>0.05). Positive

history of prenatal infection was not

significantly associated with eye problems

(p=0.273). Needed oxygen therapy on birth

was significant (p=0.002). History of

seizure, cerebral palsy, and syndromes

all were not significant (p>0.05).

Conclusion: Strabismus

and abnormal visual acuity are the most

common abnormalities detected in this

study. The detected eye and vision abnormalities

were most commonly distributed in children

at the fifth and second year of life.

Key words: Prevalence,

eye and vision screening

|

Childhood blindness is a priority eye problem

in VISION 2020-The Right to Sight initiative.

[1]

Vision disorders are the fourth most common disability

of children and the leading cause of handicapping

conditions in childhood. [2]

Eye examination and vision assessment are vital

for the detection of conditions that result in

blindness, signify serious systemic diseases that

may lead to problems with school performance,

or at worst, threaten the child's life. [3,4]

Vision problems occur in 5% to 10% of all pre-schoolers

and include refractive error, strabismus, and

amblyopia. [5]

United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends

vision screening for all children at least once

between the ages of 3 and 5 years, to detect the

presence of amblyopia or its risk factors and

concludes that the current evidence is insufficient

to assess the balance of benefits and harms of

vision screening for children < three years

of age.[6]

Before adopting this screening in developing countries,

workload of such screening should be critically

reviewed to ensure its efficiency and sustainability.

[7]

In Iraq a new screening program for early detection

of eye and vision disorders in children from birth

-five years old was started in 2010.*

Aims of the study:

1.To identify the prevalence of vision and eye

abnormalities in children up to five years old

attending two of primary health care centers in

Baghdad Alresafa.

2. To identify some risk factors associated with

vision and eye abnormalities in this age group.

* Dr. Muna AttaAllah Khalefa Ali (head

of non communicable diseases unit at Iraqi Ministry

of Health).

1-Study Design :

A descriptive cross-sectional

study to identify the

prevalence of vision abnormalities

in children up to five

years old.

2-Time of the Study

This study was conducted

from the first of November

2011 to the first of March

2012

3-Place of the Study

This study was conducted

in two primary health

care centers in Baghdad

AL-Resafa; the selected

centers are:

1- Sylakh specialized

family Medicine primary

health care center.

2- AL-Mustansyria

specialized family Medicine

primary health care center.

4-Sampling Design

The sampling design was

a non-probability convenient

sample.

5-Sample size

The sample size was calculated

as (407) on a prevalence

of -5%-10% (as reported

in the USA) [3].

Sample size determination

used the formula:

N=P*Q*Z2/R2 N=0.08*0.92*(1.96)2/(0.05)2=113

N=Sample size, P=prevalence,

Q=1-P, Z=1.96, R=0.05.

6-Criteria of enrolment:

6.1 Inclusion criteria

The study population who

attended the selected

PHC centers for any complaint

was selected depending

on the following criteria:-

1) Age under five

years.

2) Children from

both sexes were included.

6.2 Exclusion criteria

1) Age above five

years old.

2) Subjects who

did not respond to screening

tests

Content of the questionnaire

After selection of the

eligible participants

(the parents), then clarification

of the purpose behind

the study, assuring high

confidentiality, and having

verbal consents were done.

And all the eligible willing

participants were subjected

to a self -structured

closed ended questionnaire

consisting of :

• Age at the time

of examination

• Gender

• Is there a family

history of vision problems

(e.g., cataracts, nystagmus,

congenital glaucoma, eye

crossing and/or needing

glasses In Young age?

• Was your child

exposed to any prenatal

infections (e.g. rubella,

toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus,

hepatitis)?

• Child weight at

birth?

• Gestational age

at birth?

• Has your child

had meningitis or encephalitis?

• Has your child

experienced some form

of head trauma?

• Does your child

have a seizure disorder?

• Does your child

have any difficulties

with his or her hearing,

Cerebral palsy, diagnosed

with a syndrome e.g. Down

syndrome?

All children were subjected

to the following examinations

by the researcher alone

using the same equipment

for all: [8]

1. Inspection:

Inspection of all

children's eyes and

eyelids for any abnormalities

like eye deviation,

limited eye movement,

involuntary jerky movement,

red eye, watery, cloudiness

of eye, drooping eyelid

or any other abnormality.

2. Red reflex examination:

The test was done for

all children and was

performed in a darkened

room (to maximize pupil

dilation). The direct

ophthalmoscope is focused

on each pupil individually

approximately 12- 18

inches away from the

eye, and then both eyes

are viewed simultaneously.

The red reflex seen

in each eye individually

should be bright reddish-yellow

(or light gray in darkly

pigmented, brown-eyed

patients) and identical

in both eyes. Dark spots

in the red reflex, blunted

dull red reflex, lack

of a red reflex, or

presence of a white

reflex are all indications

for referral. After

assessing each eye separately,

the eyes are viewed

together with the child

focusing on the ophthalmoscope

light (Bruckner test)

as before, any asymmetry

in red reflex colour,

brightness, or size

is an indication for

referral, because asymmetry

may indicate an amblyogenic

condition.

3. Corneal Light

Reflex Test:

All children older than

three months should

be examined holding

a penlight 12-13 inches

away from the child's

face directly in front

of the eyes. The child

needs to fixate either

on the penlight or an

object that may be held

near the light. The

examiner should observe

the reflection of the

penlight in the pupils

of both eyes. The reflection

should be centered or

equally centered slightly

toward the nose (nasal).

If the reflection is

symmetrical and centered

in both eyes it is normal.

If the reflection of

the penlight does not

appear to be in a centered

position in the pupil

of each eye it is considered

abnormal. Sensitivity

to light, rapid eye

movement, and poor fixation

observed during this

test are also reasons

for referral for further

evaluation.

4. Near Fixation:

All children older than

three months should

be examined. A 1-inch

object is to be placed

from (8-18) inches away

from the child's face

and observe whether

the child looks at the

object. If the child

does not look at the

object, it can be picked

up and shown to the

child. If the child

fixates on the object

(looks with sustained

gaze for 2-3 seconds)

it's a normal finding

but if the child cannot

fixate on the object

or maintain fixation

it's considered an abnormal

finding.

5. Ocular Motility

Test:

Smooth tracking skills

should be evident after

3 months of age.

Horizontal Tracking:

Position the object

or light about 12 inches

from the child's eyes.

Move the object to get

the child's attention

and let him or her look

at it for 2-3 seconds.

Slowly move the object

in an arc of 180 degrees

from one side to the

other and back to the

other side.

Vertical Tracking:

Position the object

about 12 inches in front

of the child's nose.

Move the object to get

the child's attention

and let him or her look

at it for 2-3 seconds.

Slowly move the object

up to several inches

above the child's head

and then down to several

inches below his or

her chin. If the tracking

is described as jerky

or segmented it is abnormal.

If both eyes maintain

their gaze on the oncoming

object at least 4-6

inches from the nose

it is normal.

6. Cover Test:

Start by 6 months age.

The target object (small

toy) may need to be

manipulated or changed

to maintain a young

child's attention. Position

the child sitting in

caregiver's lap or independently

in a chair. The room

should be quiet to reduce

unnecessary distraction.

The examiner sits across

from the child and aligns

his or her eyes with

the child's eyes. Hold

the target object about

12 inches away directly

in front of the child.

Get the child to fixate

on the object for 2-3seconds.

This can be checked

by moving the object

back and forth and watching

the child's eyes follow.

The child's right eye

should be covered with

the occluder, watching

the left eye for any

movement, the cover

should be left for 2-3

seconds then quickly

move the occluder across

the bridge of the nose

to cover the left eye,

watching the right eye

for any movement, waiting

2-3 seconds after the

cover is moved to permit

fixation of the now

uncovered eye, moving

the cover from the left

eye back to the right

eye, across the bridge

of the nose, watching

the left eye for any

movement then we allow

2-3 seconds for fixation.

Repeat procedure several

times to be assured

of observations. If

there is no redress

movement in either eye;

the child will pass

this screening indicator.

If there is redress

movement in either eye,

the child will fail

this indicator and should

be referred for further

evaluation.

7. Visual Acuity

(V.A) Test:

All children from 36

months old were examined,

using Snellen picture

chart. The examiner

shows the child the

pictures on the chart

up close and asks the

child to give a name

for each picture. The

child looks at the chart

which is placed 20 feet

(6 meters) from the

child. The child or

his or her parent occluding

one eye and the child

should be able to identify

at least 3 pictures

from 5 at each line

to pass that line. If

the child has a V.A

of 20 /40or 6 /12 his

or her V.A is considered

normal at that eye,

one eye should be evaluated

at a time. [8]

Data analysis:-

SPSS v.18 (Statistical

Package for Social Sciences

version 18) was used

for data input and analysis.

Continuous variables

were presented as mean

with its standard deviation

(SD) and discrete variables

presented as numbers

and percentages. Chi

square test for goodness

of fit was used to test

the significance of

observed distribution.

Those who did not undergo

a specific examination

or test were not included

in related analysis.

Chi square test for

independence and Fisher

exact test were used

as appropriate to test

the significance of

association between

observed findings. P

value used for all tests

was asymptotic and two

sided. Findings with

a P value less than

0.05 were considered

significant.

The total number of

children who were involved

in this study is 407;

the minimum age was

2 weeks and the maximum

age 59 months; the mean

of ages was 16.6 months;

standard deviation is

15.1.

The personal characteristics

for the study sample

according to presence

or absence of eye problems:

There is a significant

association between

age and having eye problems

with the majority of

eye problem cases aged

more than one year (p<0.001),

(Table 1).

Table 1: Personal characteristics

for the study sample

according to presence

or absence of eye problem

| |

positive

eye

problem N=25

|

100%

|

negative

eye problem N=382

|

100%

|

P

value

|

| Year

of Life |

|

|

|

|

|

| First |

3

|

12.0

|

180

|

47.1

|

|

| Second |

10

|

40.0

|

124

|

32.5

|

|

| Third |

1

|

4.0

|

35

|

9.2

|

<0.001

|

| Fourth |

0

|

0.0

|

21

|

5.5

|

|

| Fifth |

11

|

44.0

|

22

|

5.8

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

| Male

|

12

|

48.0

|

143

|

37.4

|

0.512

|

| Female |

13

|

52.0

|

239

|

62.6

|

|

| GA<

37 Week |

6

|

24.0

|

54

|

14.1

|

0.178

|

Birth

Weight

< 2.5 kg |

5

|

20.0

|

12

|

3.1

|

<0.001

|

There was no significant

association between

sex and having eye problem

(P=0.512). Prematurity

was not significantly

associated with eye

problems in the study

sample ( p=0.178). Low

birth weight was significantly

associated with eye

problems in the study

sample (p<0.001),

(Table 1 ).

History findings of

the study sample according

to presence or absence

of eye problems was

as follows: The number

of children with eye

problems was 25 and

the number of children

with no eye problems

was 382. Family history

of glaucoma, eye deviation,

wearing glasses during

childhood, all were

significantly associated

with eye problems in

the study sample (p<0.05)

for each, but family

history of nystagmus

was not significant

(p=0.06). There was

no family history of

cataract. Positive history

of prenatal infection

was not significantly

associated with eye

problems in the study

sample (p=0.57). Needed

oxygen therapy on birth

was significant (p=0.002).

History of seizure,

cerebral palsy, and

syndromes all were not

significant (p>0.05).

There were no cases

of hearing difficulty,

history of meningitis,

encephalitis or head

trauma, (Table 2 ).

Table 2: History

findings for the study

sample according to

presence or absence

of eye problems

| |

N

=25

|

100%

|

N=382

|

100%

|

P

value

|

| Family

history |

|

|

|

|

|

| Positive

for eye problems |

9

|

36.0

|

11

|

2.9

|

<0.001

|

| of

Cataract |

0

|

0.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

-

|

| of

Nystagmus |

1

|

4.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

0.061

|

| of

Glaucoma |

3

|

12.0

|

0

|

0.9

|

<0.001

|

| of

eye deviation |

2

|

4.0

|

3

|

0.8%

|

0.032

|

| Wearing

Glasses during childhood |

3

|

12.0

|

10

|

2.6

|

0.039

|

| Positive

History of Prenatal

Infection |

1

|

4.0

|

4

|

0.1

|

0.273

|

| History

of Needed Oxygen

Therapy on Birth |

4

|

16.0

|

2

|

0.5

|

0.002

|

| History

of Meningitis or

Encephalitis |

0

|

0.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

-

|

| History

of Head Trauma |

0

|

0.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

-

|

| History

of Seizure |

1

|

4.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

0.061

|

| History

of Hearing Difficulty |

0

|

0.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

-

|

| History

of Cerebral Palsy |

1

|

4.0

|

0

|

0.0

|

0.061

|

| History

of Syndromes |

1

|

0.0

|

1

|

0.3

|

0.119

|

Inspection finding

for study sample. The

total number of inspection

abnormalities was 24

(5.9%), 3 (0.9%) children

had watery eye, 1 child

(0.2%) had cloudy eye,

18 (4.4%) had eye deviation,

2 (0.5%) children had

nystagmus; no child

had red eye, irritated

eye or drooping of eyelids,

(Table 3).

Table 3: Inspection

findings for study sample

| |

N

= 407

|

100.0%

|

| Red

Eye |

0

|

0.0

|

| Irritated

Eye |

0

|

0.0

|

| Watery

Eye |

3

|

0.9

|

| Cloudy

Eye |

1

|

0.2

|

| Eye

Deviation |

18

|

4.4

|

| Nystagmus |

2

|

0.5

|

| Drooping

of Eyelids |

0

|

0.0

|

| Total

No. of abnormalities |

24

|

5.9

|

Examination findings

of study sample was

24 (5.8) children having

abnormal finding by

inspection. 8 (2%) children

had abnormal red reflex,

17 (4.1%) had abnormal

corneal reflex, 4(1%)

children had abnormal

fixation test. 5 (1.2

%) children had abnormal

fixation and flow (horizontal).

4 children (1%) had

abnormal fixation and

flow (vertical). 17

(4.1%) had abnormal

cover test. 6 (1.4%)

had abnormal visual

acuity, (Table 4).

Table 4: Examination

findings for study sample

| |

N

= 407

|

100.0%

|

| Inspection |

|

|

| Normal |

383

|

94.1

|

| Abnormal |

24

|

5.8

|

| Red

Reflex |

|

|

| Normal |

399

|

98.0

|

| Abnormal

Red Reflex |

8

|

2.0

|

| Corneal

Reflex |

|

|

| Symmetrical |

256

|

62.9

|

| Not

Symmetrical |

17

|

4.1

|

| Not

done * |

134

|

32.1

|

| Fixation

test |

|

|

| Normal |

346

|

85.0

|

| Not

normal |

4

|

1.0

|

| Not

done * |

57

|

14.0

|

| Fixation

and Flow Horizontal

) |

|

|

| Smooth |

345

|

84.8

|

| Not

Smooth/segmented |

5

|

1.2

|

| Not

done * |

57

|

14.0

|

| Fixation

and Flow (Vertical) |

|

|

| Smooth |

346

|

85.0

|

| Not

Smooth/segmented |

4

|

1.0

|

| Not

done * |

57

|

14.0

|

| Cover

Test |

|

|

| Normal |

256

|

62.9

|

| Abnormal

Cover Test |

17

|

4.1

|

| Not

done * |

134

|

3212

|

| Visual

Acuity |

|

|

| Normal |

46

|

11.3

|

| Abnormal

Visual Acuity |

6

|

1.4

|

| Not

done * |

355

|

87.2

|

* children not included

in the test because of

their age

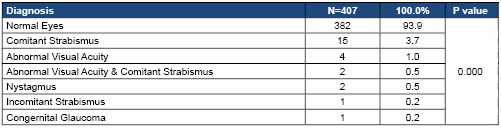

The distribution of

study sample according

to eye status was: 382

(39.9%) had normal eyes.15

(3.7%) had comitant

strabismus, 4(1%) had

abnormal visual acuity,

2 (0.5%) abnormal visual

acuity and comitant

strabismus. 2 (0.5%)

had nystagmus and 1

(0.2%) have incomitant

strabismus. 1 (0.2%)

had congenital glaucoma,

(Table 5).

Table 5: Distribution

of study sample according

to eye status.

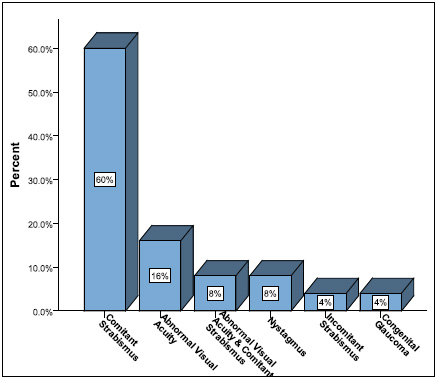

The distribution of

eye problems in children

with eye abnormalities,

were comitant strabismus

(60%), abnormal (VA.)

(16%), comitant strabismus+

abnormal (VA) is (8%),

nystagmus (8%), incomitant

strabismus (4%) and

congenital glaucoma

(4%), (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The distribution

of eye problems in children

with eye abnormalities

The prevalence of

eye and vision abnormalities

in the study sample

were:

The prevalence of all

eye abnormalities was

6.14% (95%CI 4.09% -

9.0.5%), the prevalence

of strabismus was 4.42

%, abnormal visual acuity

1.5%, nystagmus 0.5%

and congenital glaucoma

0.25% (Table 6).

Table 6: Shows the

prevalence of eye and

vision abnormalities

in the study sample

| Diagnosis |

Prevalence

|

95%CI

|

| Strabismus |

4.42

%

|

2.32-6.40

|

| Abnormal

Visual acuity |

1.50%

|

0.62-3.38

|

| Nystagmus |

0.50

%

|

0.09-1.97

|

| Congenital

gluacoma |

0.25

%

|

0.01-1.59

|

| Total |

6.14%

|

4.09

- 9.0.5

|

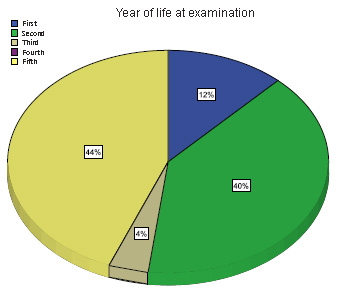

The distribution of

children with eye problems

according to the age

(year of life) at examination

shows that maximum distribution

is in the fifth (44%)

and second (40%) year

of life, no children

with eye problems were

found in the study sample

in the fourth year of

life, (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Distribution

of children with eye

problem according to

the age (year of life)

at examination

In

this

study,

the

prevalence

of

eye

and

vision

abnormalities

among

children

up

to

five

years

old

is

6.14%

(95%

CI

is

4.09%

-

9.05%)

and

this

goes

with

prevalence

of

American

Academy

of

Pediatrics

where

prevalence

of

vision

abnormalities

is

5%

to

10%.

[5]

The

prevalence

of

strabismus

is

4.4%

which

is

close

to

Rajiv

Khandekar

et

al's

study

in

Oman

and

Bardisi

et

al

in

Saudi

Arabia

where

the

prevalence

of

strabismus

was

2.9%

and

6%

respectively.

[7,

9]

This

is

also

similar

to

other

studies

in

the

USA

where

the

prevalence

was

4%.[10,

11]

The

prevalence

of

abnormal

visual

acuity

is

1.5%,

which

is

close

to

the

Al-Rowaily

study

in

Saudi

Arabia

which

was

4.5%.

[12]

The

prevalence

of

nystagmus

is

0.5%.

This

is

similar

to

Shirzadeh

et

al's

study

in

Iran

0.5

%

[13]

and

close

to

Rajiv

Khandekar

et

al's

study

in

Oman

which

was

1.2%.

[7]

The

prevalence

of

congenital

glaucoma

is

0.2%,

while

in

Zeidan

et

al's

study

in

Sudan

it

was

2.5

%,

[14]

and

according

to

the

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology

it

was

0.01%

in

the

USA.

[15]

This

may

be

due

to

different

samples

size

among

these

studies.

The

distribution

of

children

with

ocular

abnormalities

in

regard

to

year

of

life

was

significant

in

that

the

majority

were

from

the

second

and

fifth

years

of

life

while

in

Rajiv

Khandekar

et

al's

study

the

distribution

of

children

with

ocular

abnormalities

was

significant

in

the

second

and

fourth

years

of

age.

[7]

This

may

be

due

to

the

larger

number

of

children

attending

primary

health

care

centers

during

the

fifth

year

of

life

according

to

the

immunization

program,

and

older

children

respond

better

than

those

who

are

younger

age

for

assessment

of

V.A.

by

Snellen

chart.

There

is

no

significant

association

between

sex

and

having

eye

problem

and

this

goes

with

Al-the

Rowaily

study

in

Saudi

Arabia.

[12]

This

study

shows

that

low

birth

weight

was

significantly

associated

with

eye

problems

and

this

goes

with

Rajiv

Khandekar

et

al's

study

in

Oman

and

Saw

et

al's

study

in

the

USA.

[7,16]

Prematurity

was

not

significantly

associated

with

eye

problems

and

this

goes

with

Rajiv

Khandekar

et

al's

study,

[7]

while

in

the

Dowdeswell

et

al

study

in

USA,

prematurity

was

associated

with

eye

and

vision

defect.

This

discrepancy

occurs

because

most

premature

children

in

this

study

were

born

after

the

32nd

week

of

gestation

while

in

the

Dowdeswell

et

al

study,

all

children

were

born

before

the

32nd

week

of

gestation.

[17]

Needed

oxygen

therapy

is

significantly

associated

with

eye

problems

in

this

study

and

this

goes

with

the

Saw

et

al

study

and

other

studies

in

the

USA.

[13,

8,

18]

Family

history

was

significantly

associated

with

eye

problems

in

this

study.

This

goes

with

publications

of

the

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology

and

different

studies

in

the

USA.

[8,16,

18

,19]

Positive

history

of

prenatal

infection

was

not

significantly

associated

with

eye

problems

in

this

study.

This

is

because

the

majority

of

eye

problems

which

were

found

like

strabismus

and

abnormal

visual

acuity,

are

not

associated

with

prenatal

infection.

History

of

seizure,

cerebral

palsy,

and

syndromes

are

not

significantly

associated

with

eye

and

vision

problems

in

this

study,

while

in

Peter

Black

et

al's

study

in

England

and

Haugen

et

al's

study

in

Norway

there

was

significant

association.

[20,

21]

This

may

be

due

to

smaller

sample

size

in

this

study.

Vision

and

eye

screening

conducted

in

a

small

sample

of

children

up

to

five

years

old

in

this

study

enabled

us

to

detect

children

with

eye

problems

for

the

first

time

in

spite

of

having

well

established

and

accessible

eye

care

services

of

primary

and

secondary

levels

within

the

reach

of

this

community.

Strabismus

and

abnormal

visual

acuity

are

the

most

common

abnormalities

detected

in

this

study.

The

detected

eye

and

vision

abnormalities

are

most

commonly

distributed

in

children

at

the

fifth

and

second

year

of

life.

1-

Vision

screening

is

recommended,

but

validity

of

such

screening

should

be

established

before

recommending

eye

screening

on

a

larger

scale.

2-

Amblyopia

is

an

avoidable

vision

defect.

In

this

study,

risk

factors

for

amblyopia

like

abnormal

visual

acuity

and

strabismus

were

identified

and

further

studies

to

identify

the

prevalence

and

the

effect

of

early

detection

and

management

of

this

abnormality

is

recommended.

3-

Efforts

should

be

encouraged

to

increase

awareness

about

the

importance

of

early

vision

assessment

and

eye

examination

firstly

among

doctors,

especially

family

physicians,

general

practitioners

and

pediatricians

who

are

in

close

contact

with

children

during

this

critical

period

of

visual

development;

secondly

among

medical

staff

and

finally

among

parents

via

lectures,

meetings

and

media.

1.

Gilbert

C,

Foster

A.

Childhood

blindness

in

the

context

of

VISION

2020-The

right

to

sight.

Bull

World

Health

Organ.

2001;79:227-32.[PubMed]

2.

Ciner

EB,

Schmidt

PP,

Orel-Bixler

D,

et

al.

Vision

screening

of

preschool

children:

Evaluating

the

past,

looking

toward

the

future.

Optom.

Vis.

Sci.

1998;75:571-584

3.

American

Academy

of

Pediatrics,

Section

on

Ophthalmology.

Proposed

vision

screening

guidelines.

AAP

News.

1995;

11:25.

4.

American

Academy

of

Pediatrics,

Committee

on

Practice

and

Ambulatory

Medicine.

Recommendations

for

preventive

pediatric

health

care

Pediatrics.

1995;

96:373-3745.

5.

Donald

H.

Tingley.

Vision

Screening

Essentials.

Screening

Today

for

Eye

Disorders

in

the

Pediatric

Patient.

Pediatrics

in

Review.

February

2007;Vol.28

No.2

:54

6.

Chou

R,

Dana

T,

Bougatsos

C.

Screening

for

visual

impairment

in

children

ages

1-5

years:

update

for

the

USPSTF.

Pediatrics

2011;127(2):e442-e479.

7.

Rajiv

Khandekar,

Saleh

Al

Harby,

and

Ali

Jaffer

Mohammed.

Eye

and

vision

defects

in

under-five-year-old

children

in

Oman.

A

public

health:

intervention

study.

Oman

J

Ophthalmology.

2010

Jan-Apr;

3(1):

13-17

8.

Tanni

L.

Anthony,

J.C.

Greeley,

Susan

Larson,

et

al.

Visual

Screening

Guidelines:

Children

Birth

through

Five

Years.

COLORADO

DEPARTMENT

OF

EDUCATION.2005:5-6.

9.

Bardisi

WM,

Bin

Sadiq

BM.

Vision

screening

of

preschool

children

in

Jeddah,

Saudi

Arabia.

Saudi

Med

J.

2002

Apr;

23(4):445-9.

10.

Donnelly

UM,

Stewart

NM,

Hollinger

M.

Prevalence

and

outcomes

of

childhood

visual

disorders.

Ophthalmic

Epidemiol

2005;12:243-50

11.

National

Advisory

Eye

Council.

Vision

Research:

A

National

Plan.

Report

of

the

Strabismus

Amblyopia,

and

Visual

Processing

Panel,

Vol

2,

Part

5.

Bethesda:

US

DHHS,

NIH

Publ

No.

83.2001,2475

12.

Mohammad

A.

Al-Rowaily.

Prevalence

of

refractive

errors

among

pre-school

children

at

King

Abdulaziz

Medical

City,

Riyadh,

Saudi

Arabia.

Saudi

Journal

of

Ophthalmology.,

April

2010;

24,

Issue

2

,

Pages

45-48.

13.

Shirzadeh

E.,

Bolourian

A.A.,

Mohamadi

Nikpoor

M.,

Bemani

Naeini

M.

A

Survey

of

Impaired

Vision

and

the

Common

Etiology

in

the

Rural

Population

of

Sabzevar,

Iran.

Journal

of

Medical

Sciences

Research;

2007:

19-22

14.

Zeidan

Z,

Hashim

K,

Muhit

MA,

Gilbert

C.

Prevalence

and

causes

of

childhood

blindness

in

camps

for

displaced

persons

in

Khartoum:

results

of

a

household

survey.

East

Mediterr

Health

J.

2007;

13(3):

580-5.

15.

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology

Basic

and

Clinical

Science

Course

Subcommittee.

Basic

and

Clinical

Science

Course.

Glaucoma:

Section

10,

2007-2008.

San

Francisco,

CA:

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology;

2007:

Chapter

6

16.

Seang-Mei

Saw,

Joanne

Katz,

Oliver

D.

Schein

,et

al.

Epidemiol

Rev

Vol.

18,

No.

2,

1996:177-180.

17.Dowdeswell

HJ,

Slater

AM,

Broomhall

J,

Tripp

J.

Visual

deficits

in

children

born

at

less

than

32

weeks'

gestation

with

and

without

major

ocular

pathology

and

cerebral

damage.

Br

J

Ophthalmol.

1995

May;79(5):447-52.

18.

Linda

M.

Christmann,

Patrick

J.

Drost,

Sid

Mandelbaum.

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology

Pediatric,

Ophthalmology/Strabismus

Panel.

Preferred

Practice

Pattern®

Guidelines.

Pediatric

Eye

Evaluations.

San

Francisco,

CA:

American

Academy

of

Ophthalmology;

2007.

Available

at:

http://www.aao.org/ppp.

19.

Lisa

A.

Jones-Jordan,

Loraine

T.

Sinnott,

Ruth

E.

Manny,

et

al.

Investigative

Ophthalmology

&

Visual

Science,

January

2010,

Vol.

51,

No.

1:115-121.

20.

PETER

BLACK.

Visual

disorders

associated

with

cerebral

palsy.

British

Journal

of

Ophthalmology,

1982;

66:

46-52

21.Haugen

OH,

Høvding

G.

Refractive

development

in

children

with

Down's

syndrome:

a

population

based,

longitudinal

study.

Br

J

Ophthalmol.

2001

June;

85(6):

714-719.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|