|

|

|

Review Paper

........................................................

Education and Training

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| November 2014

- Volume 12 Issue 9 |

|

Training

medical students in general practices:

Factors influencing patients' attitudes

R.P.J.C. Ramanayake

(1)

A.H.W. de Silva (2)

D.P. Perera (2)

R.D.N. Sumanasekera (2)

L.A.C.L.Athukorala (3)

K.A.T. Fernando (3)

(1) Senior Lecturer,

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

(2)

Lecturer,

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

(3)

Demonstrator. Department of Family Medicine,

Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya,

Sri Lanka.

Correspondence:

Dr. R. P. J. C. Ramanayake

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

PO Box 6, Talagolla road, Ragama

Sri Lanka

Mobile: 0094773308700

Email: rpjcr@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Introduction: It is

in the privacy of the consultation room

that a patient divulges information regarding

his/her illness to the doctor. Presence

of students could compromise the privacy

and intimacy and may prohibit a patient

from revealing sensitive information and

allowing internal examination. This study

was conducted to explore factors affecting

patients' attitudes towards training students

in general practices.

Methodology: Six general practices,

to represent different backgrounds (urban,

semi urban, male and female trainers)

where students undergo training, were

selected for the study. Fifty consenting

consecutive adult patients from each practice

responded to a self administered questionnaire

following a consultation where medical

students had been present.

Results: 300 patients (57.2 % females)

participated in the study. 44.1% had previously

experienced students. Patients' agreement

to the presence of students during different

stages of consultation were; 94.7% history

taking, 81.7% examination over clothes,

54% examination without shirt/blouse,

34.7% internal examination. Even though

83.3% agreed to discuss their illness

in the presence of students they were

less prepared to discuss family problems

(58.7%) and sexual problems (38.7%). Females,

younger (<35yrs), more affluent (income

> 20000LKR) and more educated

(>Gr 12) and patients seeing female

GPs were less prepared for internal examination

and discussion of family and sexual problems

in the presence of students. Previous

contact with students and location of

the practice (urban/semi urban) did not

have an impact on patients' attitudes.

Recommendations: General practitioner

trainers should be aware of the instances

where patients are reluctant to have students

during consultation and opportunity should

be offered to them to consult the doctor

without students.

Key words: Medical students, training,

General practice, patients' attitudes,

factors

|

Consultation is the pivot of family medicine and

it is the privacy or intimacy of the consultation

room which provides the patient with the opportunity

of divulging even sensitive personal information

regarding his/her problem to the doctor.(1) Presence

of students in the consultation room may compromise

the privacy and intimacy of consultation and converts

this activity between the doctor and the patient

into a triad.

During the consultation students can learn gathering

information from a patient in an out patient setting

and how to conduct a focused examination. They

can experience every aspect of patient management;

investigations, pharmacological and non pharmacological

management, and referral. This is an opportunity

for them to practice record keeping, writing prescriptions

and referral letters. More importantly this in

an environment where the importance of social,

economic, psychological and cultural influences

on a patient's illness and the family response

can be experienced first hand(2) and it is also

an opportunity for students to get an insight

into the socio-economic environment of patients

and the local resources available to them. General

practice consultations offer a highly personalized

teaching experience for students where teacher

student ratio is either one to one or one to two.

Involvement of students in general practice could

have an impact on the patient, the doctor and

the consultation. Patients may be inhibited by

the presence of students and may not divulge sensitive

information or may postpone internal examination.

Doctors may not be able to conduct the consultation

in the usual manner. Quality of the consultation

could be affected positively or negatively and

duration may become longer.

Patients' attitudes towards students may depend

on patient characteristics(3), the nature of the

problem, (4,5,6) previous experience with students(7,8,9)

and gender of the student.(10,11,12) There could

be a difference in patients' thinking patterns

between an urban practice and a rural practice

and between a practice managed by a male doctor

and a female doctor. Although there have been

numerous studies from the western world on patients'

attitudes towards students such research has been

extremely limited in Sri Lanka and South Asia.

How a different culture in the eastern world has

shaped patient thinking has not been explored

adequately. In this background this study, which

is part of a larger research project on community

based training of undergraduate medical students,

explored factors which affect patients' attitudes

on involvement of students in general practice

consultations.

The Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya,

Sri Lanka sends students to general practices

during their fourth year of training in the five

year course. They learn by observing doctor patient

encounters, taking histories, performing clinical

examinations and getting involved with the management

of patients with the GP teacher. This study was

conducted in general practices where these students

undergo training.

This descriptive cross

sectional study was conducted

in 6 general practices

purposively selected to

represent urban and semi-urban

practices as well as general

practices managed by both

male and female doctors.

A self administered questionnaire

was used to gather demographic

data, number of previous

consultations with student

participation and their

willingness to have presence

of students at different

stages of the consultation

and the factors impacting

upon willingness. Fifty

consenting consecutive

eligible patients from

each practice who consulted

the doctor in the presence

of students were invited

to respond to the questionnaire.

Patients below 16 years,

seriously ill patients,

confused or cognitively

impaired patients, who

were unable to read and

write, were excluded.

Younger patients were

excluded since they may

not be able to respond

to the questionnaire and

the opinion of the guardian

could vary depending on

the relationship to the

patient.

Ethical approval for the

study was obtained from

the ethical review committee

of the faculty of medicine,

University of Kelaniya

and the study was conducted

in 2012.

Out of the 6 general

practitioners 4 were

male doctors, while

3 practices were located

in urban areas.

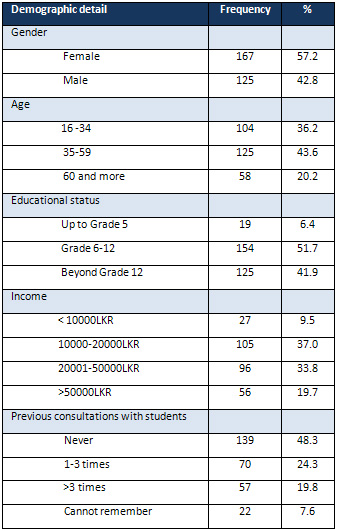

Table 1: Demographic

details of patients

n=300 note: Percentages

expressed are of valid

responses for a given

item, not for the entire

sample

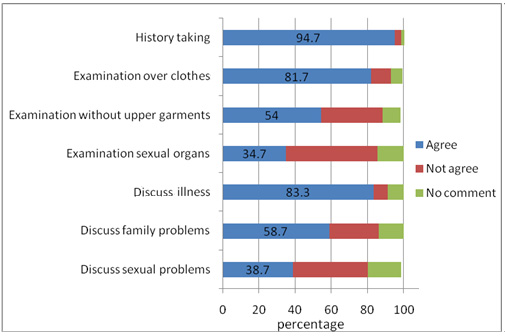

Graph 1: Patients'

overall response to

student involvement

during consultation

in different situations

Click here for Table

2: Percentage of patients

who agreed to participation

of students according

to their demographic

factors and previous

experience with students

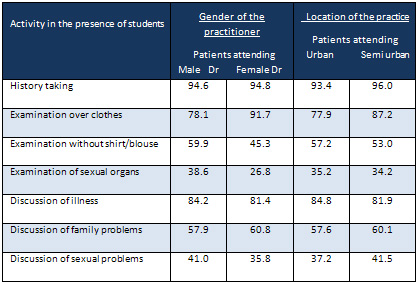

Table 3: Percentage

of patients who agreed

to participation of

students according to

practice characteristics

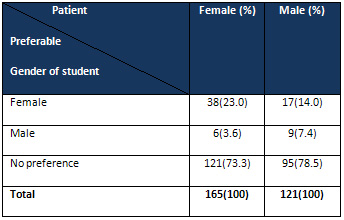

Table 4: Patients'

attitudes towards gender

of students

Pearson Chi square =5.099

p= 0.012

Patients' responses

show their positive

attitudes towards students

but it was evident that

the reason for consultation

and the nature of the

physical examination

required influenced

their decision. Even

though more than 90%

of the patients agreed

to the presence of students

during history taking,

there was resistance

to their presence during

examination. There was

a step wise decline

in the consent rate

from examination over

clothes to examination

of genital organs. This

has been a universal

phenomenon. Wright(3)

in 1974 and Choudhury

et al(9) in 2006 among

British patients and

Salisbury et al(5) in

2004 among Australian

patients observed that

there is a lesser degree

of acceptance of students

during examination compared

to history taking.

While there was little

reluctance to discuss

physical illness patients

were less prepared to

discuss family problems

and sexual problems

in the presence of students..

Research also suggested

that consent for a student

to be present is given

more readily for physical

rather than psychological

complaints(7,9,13,14)

and presence of students

could be a problem in

consultations that involved

emotional upset, internal

examinations, and sexual

problems.(15,16)

Their responses were

analysed to see if demographic

factors affect their

decisions. Gender based

analysis showed that

females were more reluctant

to have students when

it comes to internal

examination. Wright(3)

in 1974 and O'Flynn

et al(4) in 1997 described

similar difference in

attitudes between males

and females. In general

older patients were

more willing to have

students. That was more

marked for internal

examinations and discussion

of sexual problems.

Similarly patients with

better monthly income

also showed a degree

of reluctance to involvement

of students. There was

resistance among more

educated patients as

well. Earlier studies

revealed social class

had no influence on

patients' attitudes

towards students.(3,8)

The previous experience

of students had not

affected patients' attitudes

contrary to other studies

which showed that such

experience was a positive

predictor for more active

student involvement.(7,8,9)

Patients attending female

general practitioners

were more resistant

to examination without

clothes and internal

examination while there

was no difference in

their attitudes towards

students among patients

attending urban general

practices and semi urban

general practices.

Gender of the student

mattered more for female

patients. 23% of the

females preferred involvement

of female students compared

to 7.4% among males

even though this difference

was not statistically

significant. Chipp et

al(11) and Bentham et

al(10) also found that

women preferred a student

of their own sex more

often than men.

This study analysed

the effect of the nature

of the problem, demographic

factors of patients,

previous experience

of students, practice

characteristics and

gender of the student

on the thinking pattern

of patients. Nature

of the problem and type

of examination seem

to influence whether

they like the presence

of students or not most.

In general patients'

attitudes do not seem

to be quite different

from that of patients

in western countries.

•

Patients

are

willing

to

have

students

during

consultation

but

the

most

important

determinants

are

the

nature

of

the

problem

and

the

extent

of

the

examination

required.

•

Females

and

younger

patients

are

more

reluctant

to

the

presence

of

students

in

internal

examinations

and

discussion

of

sexual

problems.

•

More

affluent

and

more

educated

patients

are

less

prepared

to

have

students

during

consultation

•

More

female

patients

prefer

interaction

with

female

students

General

practitioner

trainers

should

be

aware

of

the

instances

where

patients

are

reluctant

to

have

students

during

consultation

and

opportunity

should

be

offered

to

them

to

consult

the

doctor

without

students.

1.

De

Silva

Nandani.

The

consultation

and

doctor

patient

relationship.

Lecture

notes

in

Family

Medicine.

2nd

edition.

Sarvodaya

Vishwa

Lekha

publication;

2006.

P

20.

2.

Lefford

F,

Mccroriet

P,

Perrins

F.

A

survey

of

medical

undergraduate

community-

based

teaching:

taking

undergraduate

teaching

into

the

community.

Medical

Education

1994;28:

312-315

3.

Wright

H.

J.

Patients'

Attitudes

to

Medical

Students

in

General

Practice.

Br

Med

J.

1974

Mar

2;

1(5904):

372-376

4.

O'Flynn

N,

Spencer

J,

Jones

R.

1997.

Consent

and

confidentiality

in

teaching

in

general

practice:

Survey

of

patients'

views

on

presence

of

students.

BMJ

315:1142.

5.

Salisbury

K,

Farmer

EA,

Vnuk

A.

2004.

Patients'

views

on

the

training

of

medical

students

in

Australian

general

practice

settings.

Austr

Fam

Physician

33:281-283.

6.

Haffling

AC,

Hakansson

A.

2008.

Patients

consulting

with

students

in

general

practice:

Survey

of

patients'

satisfaction

and

their

role

in

teaching.

Med

Teach

30:

622-629.

7.

Cooke

F,

Galasko

G,

Ramrakha

V,

Richards

D,

Rose

A,

Watkins

J.

1996.

Medical

students

in

general

practice:

How

do

patients

feel?

Br

J

Gen

Pract

46:361-

362.

8.

Devera-Sales

A,

Paden

C,

Vinson

DC.

1999.

What

do

family

medicine

patients

think

about

medical

students'

participation

in

their

health

care?

Acad

Med

74(5):550-552.

9.

Choudhury

TR,

Moosa

A,

Cushing

A,

Bestwick

J.

2006.

Patients'

attitudes

towards

the

presence

of

medical

students

during

consultations.

Med

Teach

28:198-203.

10.

Bentham

J,

Burke

J,

Clark

J,

Svoboda

C,

Vallance

G,

Yeow

M.

1999.

Students

conducting

consultations

in

general

practice

and

the

acceptability

to

patients.

Med

Educ

33:686-687.

11.

Chipp

E,

Stoneley

S,

Cooper

K.

2004.

Clinical

placements

for

medical

students:

Factors

affecting

patients'

involvement

in

medical

education.

Med

Teach

26:114-119.

12.

Passaperuma

K,

Higgins

J,

Power

S,

Taylor

T.

Do

patients'

comfort

levels

and

attitudes

regarding

medical

student

involvement

vary

across

specialties?

Med

Teach

2008;30(1):48-54.

13.

Benson

J,

Quince

T,

Hibble

A,

Fanshawe

T,

Emery

J.

Impact

on

patients

of

expanded,

general

practice

based,

student

teaching:

observational

and

qualitative

study.

BMJ

2005;331:89

14.

Mol

SSL,

Peelen

JH,

Kuyvenhoven

MM.

Patients'

views

on

student

participation

in

general

practice

consultations:

A

comprehensive

review.

Medical

Teacher

2011:33;e397-e

400.

15.

Monnickendam

SM,

Vinker

S,

Zalewski

S,

Cohen

O,

Kitai

E.

Patients'

attitudes

towards

the

presence

of

medical

students

in

family

practice

consultations.

Isr

Med

Assoc

J.

2001;3(12):903-6.

16.

Sweeney

K,

Magin

PJ,

Pond

D.

Patient

attitudes

Training

students

in

general

practice.

Australian

family

physician

2010;39:9:676-682

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|