|

|

|

Review Paper

........................................................

Education and Training

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| November 2014

- Volume 12 Issue 9 |

|

Review:

Ebola haemorrhagic fever

Lesley

Pocock (1)

Mohsen Rezaeian

(2)

(1) Publisher, Middle East Journal of Family

Medicine,

Queensland, Australia

(2) PhD, Epidemiologist, Social Medicine Department

Occupational Environmental Research Center

Rafsanjan Medical School

Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences

Rafsanjan-Iran

Correspondence:

Lesley Pocock

Publisher,

Middle East Journal of Family medicine,

Queensland, Australia

Email: lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

|

Abstract

This

is a review paper, on the spread of Ebola

haemorrhagic fever (Ebola) on the African

continent and beyond, and provides guidelines

for its prevention, diagnosis and treatment,

for family doctors.

Key words: Ebola,

prevention, diagnosis, treatment

|

Ebola haemorrhagic fever (Ebola) was first

documented in Zaire (Democratic Republic of

the Congo) in 1976. The reported number of human

cases at the time was 318. Of those, 88% died.

The disease was spread by close personal contact

and by use of contaminated needles and syringes

in hospitals/clinics.

In the same year there were 284 cases in South

Sudan, where the disease was recorded as Sudan

fever. The disease was spread mainly through

close personal contact within hospitals. Many

medical care personnel were infected.

With few cases in the ensuing years it emerged

again in 1979, in South Sudan with 34 cases.

65% of the infected died.

1994 saw a major re-emergence in Gabon (52 cases,

31 deaths) and in 1995 there were 315 cases

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly

Zaire).

There was 1 death in Russia in 1996, the first

case out of Africa, and a further death in Russia

in 2004. 6 asymptomatic cases were found in

the Philippines in 2008.

2000-2001 saw a major outbreak in Uganda with

425 cases with a 53% death rate. Major outbreaks

also occurred in Gabon and the Republic of Congo

in the same year.

Varying levels of outbreaks have occurred since

that time.

2014 has seen major outbreaks in Guinea, Liberia,

and Sierra Leone, with local transmission of

Ebola in Spain, (2 cases) and the USA (2 cases).

Senegal has had cases of travel-associated transmission.

Currently there are 10,000 expected new cases

of Ebola in West Africa, every week. Unfortunately

the major outbreaks are in developing nations

with limited resources, with minimal foreign

aid or assistance to these countries being generated,

Ebola now threatens the global population. (1,4)

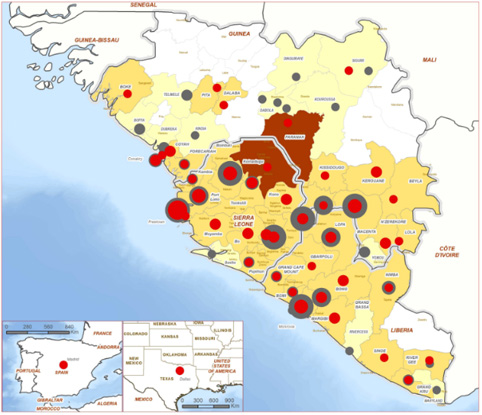

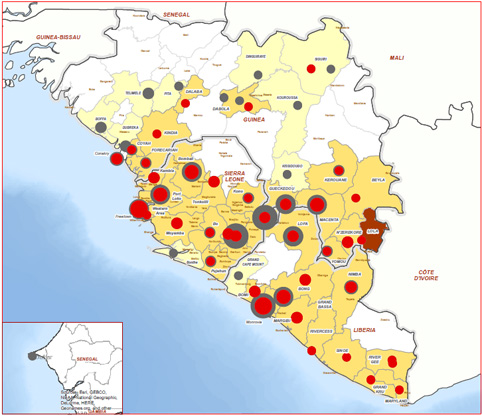

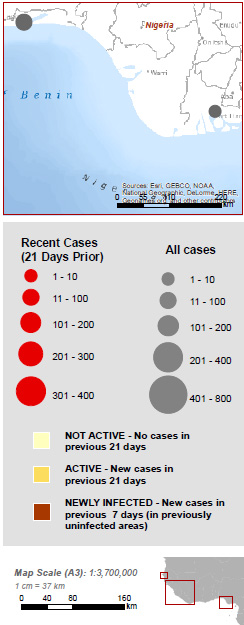

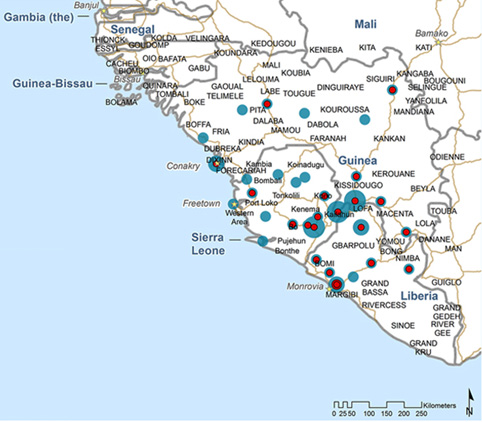

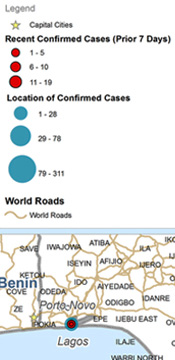

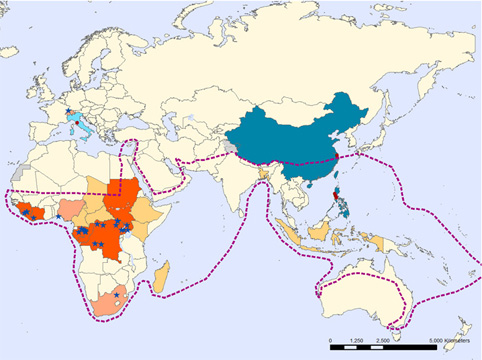

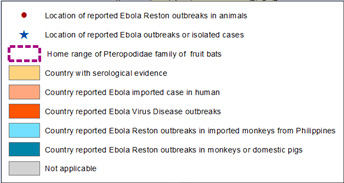

Ebola Outbreak Response Maps

WHO 2014

(Reproduced with permission from:

http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/maps/en/

)

Map 1: Regional confirmed and probable cases

- 20 October 2014

Map 2: Regional confirmed and probable cases

- 3 October 2014

Map 3- Confirmed cases of Ebola – 7

August 2014

Map 4- Geographic distribution of Ebola

virus disease outbreaks in humans and animals

- 2014

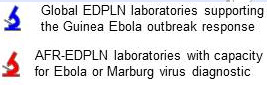

Map 5 - Laboratories for Ebola virus diagnostic

- 10 April 2014

Ebola virus is one of

a group of zoonotic viruses

that can cause severe

disease in humans. Other

viruses that cause viral

haemorrhagic fever include

Lassa virus, Crimean-Congo

haemorrhagic fever virus,

Marburg virus, and emerging

viruses such as Lujo virus.

In previous outbreaks

2,387 cases have been

reported, with a case

fatality risk of 66.7%.(2)

Of the five species of

Ebola virus, three (Zaire,

Sudan and Bundibugyo)

have been associated with

significant human to human

transmission, with the

other two (Tai Forest

and Reston) associated

with limited or no human

disease.

The current outbreak has

been caused by a new emergence

of the Zaire species.(2)

Data from previous outbreaks

suggest Ebola is moderately

transmissible in the absence

of infection control,

even in resource limited

settings. Studies have

estimated the basic reproductive

ratio (R0) at 1.3 to 2.7

in different outbreaks

(2.3) meaning that in

a completely susceptible

population with no interventions

to reduce spread, each

infected case resulted

in secondary transmission

to an average of fewer

than three people.

Symptoms of Ebola include

• Fever

• Severe headache

• Muscle pain

• Weakness

• Diarrhoea

• Vomiting

• Abdominal (stomach)

pain

• Unexplained hemorrhage

(bleeding or bruising)

Symptoms may appear

from 2 to 21 days after

exposure to Ebola, but

the average is 8 to

10 days.

Recovery from Ebola

depends on good supportive

clinical care and the

patient's immune response.

People who recover from

Ebola infection develop

antibodies that last

for at least 10 years.

(1, 4)

Because

the

natural

reservoir

host

of

Ebola

viruses

has

not

yet

been

identified,

the

way

in

which

the

virus

first

appears

in

a

human

at

the

start

of

an

outbreak

is

unknown.

Scientists

believe

that

the

first

patient

becomes

infected

through

contact

with

an

infected

animal,

such

as

a

fruit

bat

or

primate.

Person-to-person

transmission

follows

and

can

lead

to

large

numbers

of

affected

people.

Ebola

is

spread

through

direct

contact

(through

broken

skin

or

mucous

membranes

in,

for

example,

the

eyes,

nose,

or

mouth)

with

"

blood

or

body

fluids

(including

but

not

limited

to

urine,

saliva,

sweat,

faeces,

vomit,

breast

milk,

and

semen)

of

a

person

who

is

sick

with

Ebola"

objects

(like

needles

and

syringes)

that

have

been

contaminated

with

the

virus"

infected

fruit

bats

or

primates

.

(1,2,4)

Healthcare

providers

caring

for

Ebola

patients

and

the

family

and

friends

in

close

contact

with

Ebola

patients

are

at

the

highest

risk

of

transmission

because

they

may

come

in

contact

with

infected

blood

or

body

fluids

of

sick

patients.

Diagnosing Ebola in a

person who has been infected

for only a few days is

difficult, because the

early symptoms, such as

fever, are nonspecific

to Ebola infection and

are often seen in patients

with more commonly occurring

diseases, such as malaria

and typhoid fever.

However, if a person has

the early symptoms (http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/symptoms/index.html)

of Ebola and has had contact

with the blood or body

fluids of a person sick

with Ebola, contact with

objects that have been

contaminated with the

blood or body fluids of

a person sick with Ebola,

or contact with infected

animals, they should be

isolated and public health

professionals notified.

Samples from the patient

can then be collected

and tested to confirm

infection.

The following basic interventions,

when used early, can significantly

improve the chances of

survival:

• Providing intravenous

fluids (IV)and balancing

electrolytes (body salts)

• Maintaining oxygen

status and blood pressure

• Treating other

infections if they occur

Experimental vaccines

and treatments for Ebola

are under development,

but they have not yet

been fully tested for

safety or effectiveness.

•

Practice

careful

hygiene.

•

Do

not

handle

items

that

may

have

come

in

contact

with

an

infected

person's

blood

or

body

fluids

(such

as

clothes,

bedding,

needles,

and

medical

equipment).

•

Avoid

funeral

or

burial

rituals

that

require

handling

the

body

of

someone

who

has

died

from

Ebola.

•

Avoid

contact

with

bats

and

non-human

primates

or

blood,

fluids,

and

raw

meat

prepared

from

these

animals.

•

Avoid

hospitals

in

West

Africa

where

Ebola

patients

are

being

treated.

Healthcare

workers

exposed

to

people

with

Ebola

should

:

•

Wear

protective

clothing,

including

masks,

gloves,

gowns,

and

eye

protection.

•

Practice

proper

infection

control

and

sterilization

measures.

For

more

information,

see

"Infection

Control

for

Viral

Hemorrhagic

Fevers

in

the

African

Health

Care

Setting".

•

Isolate

patients

with

Ebola

from

other

patients.

•

Avoid

direct

contact

with

the

bodies

of

people

who

have

died

from

Ebola.

•

Notify

health

officials

if

direct

contact

has

been

made

with

the

blood

or

body

fluids,

such

as

but

not

limited

to,

feces,

saliva,

urine,

vomit,

and

semen

of

a

person

who

is

sick

with

Ebola.

The

virus

can

enter

the

body

through

broken

skin

or

unprotected

mucous

membranes

in,

for

example,

the

eyes,

nose,

or

mouth

•

Laboratory

workers

are

also

at

risk.

Samples

taken

from

humans

and

animals

for

investigation

of

Ebola

infection

should

be

handled

by

trained

staff

and

processed

in

suitably

equipped

laboratories.

Good

outbreak

control

also

relies

on

applying

a

package

of

interventions,

namely

case

management,

surveillance

and

contact

tracing,

a

good

laboratory

service,

safe

burials

and

social

mobilisation.

Community

engagement

is

key

to

successfully

controlling

outbreaks.

Raising

awareness

of

risk

factors

for

Ebola

infection

and

protective

measures

that

individuals

can

take

is

an

effective

way

to

reduce

human

transmission.

National

risk

reduction

messages

should

focus

on

several

factors:

•

Reducing

the

risk

of

wildlife-to-human

transmission

from

contact

with

infected

fruit

bats

or

monkeys/apes

and

the

consumption

of

their

raw

meat.

Animals

should

be

handled

with

gloves

and

other

appropriate

protective

clothing.

Animal

products

(blood

and

meat)

should

be

thoroughly

cooked

before

consumption.

•

Reducing

the

risk

of

human-to-human

transmission

from

direct

or

close

contact

with

people

with

Ebola

symptoms,

particularly

with

their

bodily

fluids.

Gloves

and

appropriate

personal

protective

equipment

should

be

worn

when

taking

care

of

ill

patients

at

home.

Regular

hand

washing

is

required

after

visiting

patients

in

hospital,

as

well

as

after

taking

care

of

patients

at

home.

•

Outbreak

containment

measures

including

prompt

and

safe

burial

of

the

dead,

identifying

people

who

may

have

been

in

contact

with

someone

infected

with

Ebola,

monitoring

the

health

of

contacts

for

21

days,

the

importance

of

separating

the

healthy

from

the

sick

to

prevent

further

spread,

the

importance

of

good

hygiene

and

maintaining

a

clean

environment.

1.

World

Health

Organization.

http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/maps/en/

2.

Allen

C.

Cheng,

Heath

Kelly.

Are

we

prepared

for

Ebola

and

other

viral

haemorrhagic

fevers?

Australian

and

New

Zealand

Journal

of

Public

Health.

doi:

10.1111/1753-6405.12303

3.

World

Health

Organization.

WHO

Statement

on

the

Meeting

of

the

International

Health

Regulations

Emergency

Committee

Regarding

the

2014

Ebola

Outbreak

in

West

Africa

[Internet].

Geneva

(CHE):

WHO;

2014

[cited

2014

Aug

15].

Available

from:

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-20140808/en/.

4.

CDC.

http://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/outbreaks/2014-west-africa/distribution-map.html

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|