|

|

|

Review Paper

........................................................

Education and Training

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| November 2014

- Volume 12 Issue 9 |

|

Comparison

of the medical students' self-assessment and simulated

patients evaluation of students' communication

skills in Family Medicine Objective Structured

Clinical Examination (OSCE).

Firdous

Jahan

(1)

Muhammed Moazzam (2)

Mark Norrish

(3)

Shaikh

Mohammed Naeem (4)

(1) Dr Firdous Jahan, Associate Professor,

Department of Family Medicine, Oman Medical

College

(2) Dr Muhammed Moazzam, Department of Family

Medicine, Oman Medical College

(3) Dr Mark Norrish, Academic coordinator, Academic

Partnerships Unit, Coventry University.

(4) Dr Shaikh Mohammed Naeem . Department of

Family Medicine, Oman Medical College

Correspondence:

Dr Firdous Jahan, Associate Professor, Department

of Family Medicine,

Oman Medical College, Oman

Email:

firdous@omc.edu.om

|

Abstract

Objective:

Comparison of the medical students' self-assessment

and the evaluation of students by simulated

patients regarding students' communication

skills in Family Medicine OSCE.

Introduction: Communication

is the act of conveying a message to another

person, and it is an essential skill for

establishing physician-patient relationships

and effective functioning among health

care professionals. Effective communication

can positively influence patient satisfaction

and outcomes. Health professional communication

skills do not necessarily improve over

time but can improve with formal communication

skills training.

Method:

A cross sectional study done at Oman Medical

College. All of the medical students who

signed up for an Objective Structured

Clinical Examination (OSCE) in Family

Medicine were included. As a part of the

OSCE, the student performance was evaluated

by a simulated patient. After the examination,

the students were asked to assess their

communication skills. The Calgary Cambridge

Observation Guide formed the basis for

the outcome measures used in the questionnaires.

A total of 12 items were rated on a Likert

scale from 1-5 (strongly disagree to strongly

agree).

Results: 68

students participated in the examination,

88% (60/68) of whom responded to the questionnaire.

The response rate for the simulated patients

was 100%. Over all comparison showed that

students marginally over estimated in

few areas as compared to simulated patients.

Measures of reliability show that it is

a reliable measure with Cronbach's Alpha

from the 12 items being 0.89. When comparing

between the experience and new simulators

only one item (q12) showed a statistically

significant difference, with t(16)=3.08,

p<0.05, with experienced simulators

giving a higher score 4.55, when compared

with the new simulators 3.86.

Conclusion: Students'

and simulated patients' assessment has

some agreements. Self-assessment is guiding

the future learning, providing reassurance,

and promoting reflection which helps them

to perform appropriately.

Key Words: Self-assessment,

communication skills, Calgary Cambridge

observation guide; Communication skills

training, under graduate medical student

|

Communication skills' training is an essential

component of medical education. Communication

is a process by which meaning is conveyed to create

shared understanding[1]. It is a skill that can

be taught and learnt; students learn this competency

in an effective learning environment. It is an

essential skill for safe, effective, and compassionate

health care to improve better outcomes in health

care system and good communication skills are

more likely to make patients satisfied with the

care they receive[2]. Learners are expected to

be actively involved and coached in communication

by their teachers specially the features of clinical

competence like empathy, compassion, counseling,

and showing support to patients[3-4]. The most

difficult aspect of the doctor-patient relationship

is ability to convey distressing news to the patients

and their relatives. Breaking bad news is an inevitable

part of medical practice[5-7]. The development

of effective communication skills is an important

part of becoming a good doctor; with appropriate

teaching, these skills can be both acquired and

retained[8]. Integrating communication with other

clinical skills- with history taking, physical

examination, and medical problem solving, help

them in real-life practice[9-10].

Interviewing real patients in real practice has

been shown to be valuable for learning communication

skills and understanding patient illnesses. The

UK's General Medical Council (GMC) emphasizes

effective communication as fundamental to good

medical practice[11].

To implement a more comprehensive approach, Calgary-Cambridge

guides is an effective tool used to teach medical

students' communication skills and practice in

a comprehensive clinical method[12]. Educators

can adopt the methods for teaching communication

that are more effective to help learners cultivate

the skills required as well as help learners set

realistic goals, and teachers should know when

and how to provide feedback to the learners in

a way that allows a deepening of skills and a

promotion of self-awareness[13-14]. Standardized

or simulated patients are used for role playing

specific communication skills or solving certain

patient problems. Simulations are good for improving

certain communication skills, and are effective

in teaching and assessing communication skills.

Teaching and Learning communication skills

at Oman Medical College:

Oman Medical College (OMC) is the only private

medical college in Oman, and offers a seven-year

curriculum, leading to the degree of Doctor of

Medicine (MD). In the 4th year (first preclinical

year) they learn Physical Diagnosis and Clinical

Integration (PDCI) clinical skills. History taking

and physical examination is conducted in the skills

lab on simulated patients(16 sessions). At the

end of the course, 2 theory exams and 1 clinical

exam are done on simulated patients(SP). In the

5th Year of PDCI they learn clinical history taking

and examination on real patients in the hospital

(32 sessions). At the end of the course Theory

Exam and Practical exam of clinical skills is

done on real patients in Sohar Hospital. Communication

skills teaching and assessment is an integral

part of clinical teaching in clinical years 6

and 7 at OMC. The Family Medicine department organizes

special communication skills sessions to help

the students communicate with their patients.

They learn knowledge of basic communication concepts,

communication models, types and functions of non-verbal

communication, ability to elicit accurate, comprehensive

and focused medical histories as well as communication

in different difficult and special situations.

Although communication skills are the integral

part of every patient encounter there are few

specialized skills they learn during Family Medicine

rotation like breaking bad news, smoking cessation

counseling, confidentiality, how to handle a difficult

patient, counseling for chronic diseases (Diabetes,

Hypertension, Obesity), Palliative and Geriatric

care.

Self-assessment is used to assess the outcome

of continuous professional development using questionnaires

and checklists focusing on skills, such as performance

skills and general clinical skills. Calgary Cambridge

Observation Guide is used as a basis for the self-efficacy

and objective assessment scores; the evaluation

tools closely match the communication skills taught.

Their communication skills are assessed during

the real consultation in the clinic as well as

mid rotation and end of rotation in Objective

Structured Clinical examination (OSCE). In the

OSCE setting simulated, standardized patients

are used for role playing different scenario.

Simulators training are done by faculty of family

medicine department maintaining a bank for simulators.

At the end of each OSCE there is a feedback session

with simulators regarding students' approach towards

patient and communication skills. OMC maintains

a SP bank managed by faculty of family medicine.

The criteria to choose SP are; minimum education

high school graduate, good English communication,

volunteers and actors, living within the city.

General training program is to give them orientation

about OMC and students, OSCE and its conduct.

Special training sessions are done twice, 4 weeks

before OSCE on a specific scenario carefully written

and reviewed by family medicine faculty. The scenario

is than discussed and role play with the SP.

In final MD OSCE 10 live stations were placed

including: A young female with lymphocytic leukemia

diagnosis as breaking bad news, a male with ureteric

colic and hematuria, a young female with Irritable

Bowel Syndrome, father of one year old child develops

febrile fit, middle aged male with community acquired

pneumonia, a middle aged male hypertensive with

recurrent Transient Ischemic Attack, an elderly

male with diabetes mellitus as follow up, a middle

aged women with menorrhagia (Dysfunctional uterine

bleeding), young boy with acute hepatitis for

abdominal examination and a young male with right

knee injury for examination of knee joints.

All stations had trained SP and all stations had

built in communication skills during consultation.

The overall objective was how the students approach

to the patient identifies the problem and manages

it. Total duration for each station was 7 minutes.

This study aimed at the comparison of students'

self-assessment and simulated patients' assessment

on students' communication skills at the end of

Family Medicine final MD OSCE.

A

cross

sectional

study

done

on

all

of

the

medical

students

who

were

signed

up

for

an

Objective

Structured

Clinical

Examination

(OSCE)

at

the

Oman

Medical

College,

June

2013

were

included

in

this

study.

There

were

2

sessions

for

simulators

training

for

the

exam

and

survey

questionnaire

by

faculty.

Questionnaires

The

Calgary-Cambridge

Observation

Guide

Checklist

formed

the

basis

for

the

outcome

measures

used

in

the

questionnaires

to

the

students

[12],

the

simulated

patients.

Twelve

items

were

chosen,

covering

domains

of

the

checklist

(initiating

the

session,

gathering

information,

building

relationship,

giving

information,

explaining

and

planning,

and

closing

the

session).The

students

were

asked

to

assess

how

confident

they

felt

being

able

to

successfully

manage

each

of

the

12

different

communication

skills

rated

on

a

Likert

scale

in

categories

1-5

(strongly

disagree

to

strongly

agree).

The

simulated

patients

were

asked

to

assess

how

the

students

succeeded

in

managing

the

12

skills

rated

on

a

similar

Likert

scale.

Validation

of

the

questionnaires

was

done.

A

pilot

test

was

performed

to

assess

the

feasibility

of

answering

the

questionnaires

for

the

standardized

patients

and

students

during

a

similar

OSCE

examination

6

months

prior

to

the

study.

Sixty eight students

participated in OSCE

of whom 60 responded

to the questionnaire,

of these -52 were women,

8 men. The response

rate for the simulated

patients was 100%.

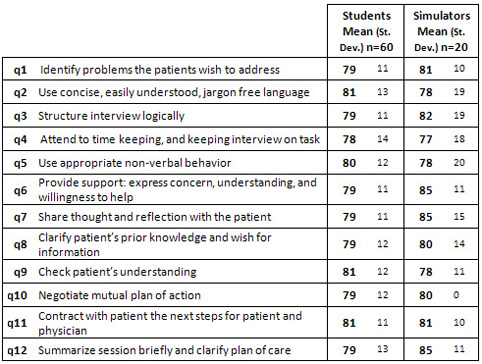

Comparison of student

self-assessment and

simulated patient evaluation

scores,when including

all 12 items evaluated.

Overall comparison showed

that students marginally

over estimated in Q

2,4,5 and 9, while remaining

items showed under estimation

(Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage

scores for each Item.

Likert scores for each

item (from 1-5) are

presented here as percentages

Measures of reliability

show that it is a reliable

measure with Cronbach's

Alpha from the 12 items

being 0.89. There is

one item (q10) where

the simulators show

an unusual pattern of

responses.

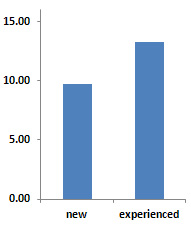

When comparing between

the experience and new

simulators only one

item (q12) showed a

statistically significant

difference, with t(16)=3.08,

p<0.05, with experienced

simulators giving a

higher score 4.55, when

compared with the new

simulators 3.86.

Good and appropriate

communication skills

are essential for medical

students to become an

efficient member of

a health care team in

future. Self-assessment

is guiding future learning,

providing reassurance,

and promoting reflection

which helps them to

perform appropriately

in examination[15-16].

They can reinforce students'

intrinsic motivation

to learn and inspire

them to set higher standards

for themselves[17].

In our study medical

students in the self-assessment

of communication skills,

do not overestimate

their skills. Students

have shown appropriate

self-assessment in one

of the history taking

stations; the literature

also support student's

self-assessment is good

for history taking attributes

in an OSCE[18]. Some

differences are also

shown, as they have

only marginally overestimated

their communication

skills in questions

2, 4, , 5 and 9. As

reported in literature

that communication skills

assessment measures

broader aspects of attitudes

towards learning communication

skills this may turn

out to be helpful for

monitoring the effect

of different teaching

strategies on students'

attitudes during medical

school.[19]. Another

study has shown that

students scored their

communication skills

lower compared to observers

or simulated patients.

The differences were

driven by only 2 of

12 items[20]. The results

in this study indicate

that self-efficacy based

on the Calgary Cambridge

Observation guide seems

to be a reliable tool

that can be used for

formative assessment

of health professionals

[21].

In Q10 of our study

there is no variance

in the simulators responses;

that is all simulators

chose "agree".

This lack of variance

is likely to indicate

that for this question

the simulators did not

feel confident to 'stray'

away from a default

answer. They may not

have understood the

question or may not

have felt confident

to assess it. Since

numbers are quite small

this is difficult to

ascertain. Question

number 11 seems to have

full agreement.

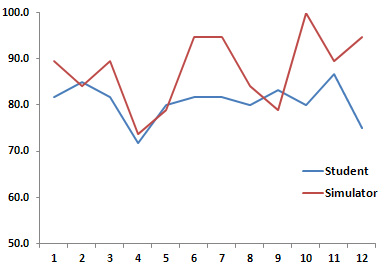

There is difference

seen when we have done

regression respondents

who agreed and strongly

agreed(Figure 2). Another

interesting finding

was seen in the extreme

end of Likert scale

which is strongly agree(Figure

3). While the students

seem very consistent

in the item ratings,

with the average for

all items being between

10 and 20% for "strongly

agree", the simulators

usage of "strongly

agree" is much

more variable, with

average score ranging

from 0% to nearly 40%.

Figure 2: The percentage

of respondents (students

and simulators) who

"agreed" or

"strongly agreed"

with the items

Figure 3: The percentage

of respondents (students

and simulators) who

used the extreme end

of the Likert scale

("strongly agree")

While the students

seem very consistent

in the item ratings,

with the average for

all items being between

10 and 20% for "strongly

agree", the simulators

usage of "strongly

agree" is much

more variable, with

average score ranging

from 0% to nearly 40%.

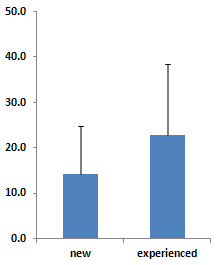

It appears that on average

the experienced simulators

are more likely to use

the extreme end of the

rating scale(Figure

4). One study has reported

that simulators' training

compared with pre workshop

standardized patient

encounters, post workshop

encounters showed significant

improvement in communication

skills [22].

Figure 4: The percentage

of simulators who used

the extreme end of the

Likert scale ("strongly

agree"), with comparison

between the new simulators

and the experienced

simulators

It appears that on

average the experienced

simulators are more

likely to use the extreme

end of the rating scale.

Standardized or simulated

patients or use of well-trained

actors is an alternative

way of role playing

specific communication

skills or solving certain

patient problems. Simulations

can mirror reality quite

closely and are good

for improving certain

communication skills,

such as counseling and

breaking bad news. Standardized

patient simulations

are effective in teaching

and assessing communication

skills[23]. In our study

the experienced simulators

have a higher intra-variance,

and thus they are more

willing to use a wider

range of scores in their

assessments, while the

'new' simulators, might

be a little more cautious

so are therefore using

a more narrow and restricted

range of scores in their

assessments (Figure

5). One study has shown

detailed constructive

feedback to students

from SPs is a feature

of SP contribution to

student learning[24].

Eva has reported that

, self-assessment serves

several potential functions

learning communication

and clinical skills,

becomes a part of the

training of healthcare

professionals and it

appears to be evident

and generally accepted

that communication skills

are core competencies

essential for good patient

care[25-26]. During

the training period

students are exposed

to real as well as simulated

patients. They can practice

this attribute under

supervision. Preliminary

research does indicate

that self-assessment

of clinical skills in

medical schools improves

the ability to self-assess

in clinical practice

[27]. Literature has

proven that introduction

and integration of structured

communication skills

teaching in early years

contributes greatly

in the development of

students' strengths.

The interactive examination

may be a convenient

tool for providing deeper

insight into students'

ability to prioritize,

self-assess and steer

their own learning [28].

Figure 5: This figure

shows the intra-rater

variance for the new

and experienced simulators

Limitation: Our

study is done on final

year medical students

at exit level exam who

may have some undue

pressure on them.

Medical

students

in

the

self-assessment

of

communication

skills,

do

not

overestimate

their

skills;

students

seem

very

consistent

in

the

item

ratings

.Students

and

simulated

patients'

assessment

has

some

agreements.

Self-assessment

is

guiding

the

future

learning,

providing

reassurance,

and

promoting

reflection

which

helps

them

to

perform

appropriately.

Acknowledgement:

The

author

would

like

to

acknowledge

Dr.

Thomas

A.

Heming,

(Vice

Dean

for

Academic

Affairs

Professor

and

Head,

Department

of

Physiology

and

Biochemistry,

Oman

medical

college)

and

Dr

Saleh

Al

Khusaiby

(Dean

Oman

medical

college)

Click

here

for

Survey

Questionnaire

for

Simulated

Patients

and

Survey

Questionnaire

for

Students

1.

Maguire

P,

Pitceathly

C.

Key

communication

skills

and

how

to

acquire

them.

British

Medical

Journal.

2002;325(7366):697-700.

2.

Aspegren

K,

Lønberg-Madsen

P.

Which

basic

communication

skills

in

medicine

are

learnt

spontaneously

and

which

need

to

be

taught

and

trained?

Med

Teacher.

2005;27(6):539-543.

3.

Sargeant

J,

MacLeod

T,

Murray

A.

An

inter

professional

approach

to

teaching

communication

skills.

Journal

Continuing

Education

in

Health

Professions.

2011

Fall;31(4):265-7.

doi:

10.1002/chp.20139.

4.

Brown

RF,

Bylund

CL.

Communication

skills

training:

describing

a

new

conceptual

model.

Academic

Medicine.

2008;83(1):37-44

5.

Deveugel,

M.,

Derese,

A.,

De

Maesschalck,

S.

Willems,

S,

Van

Driel,

M,De

Maeseneer,

J

.

Teaching

communication

skills

to

medical

students,

a

challenge

in

the

curriculum?

Patient

Education

Counseling.

2005,

58,

265-270.

6.

Back

AL,

Arnold

RM:

Discussing

prognosis:

How

much

do

you

want

to

know?''

talking

to

patients

who

are

prepared

for

explicit

information.

J

Clin

Oncol

2006;24:4209-4213.

7.

Back

AL,

Arnold

RM,

Baile

WF,

Tulsky

JA,

Barley

GE,

Pea

RD,

Fryer-Edwards

KA:

Faculty

development

to

change

the

paradigm

of

communication

skills

teaching

in

oncology.

J

Clin

Oncol

2009;27:1137-1141.

8.

Ammentorp

J,

Sabroe

S,

Kofoed

P-E,

Mainz

J.

The

effect

of

training

in

communication

skills

on

medical

doctors'

and

nurses'

self-efficacy:

a

randomized

controlled

trial.

Patient

Educ

Couns.

2007;66(3):270-277.

9.

Jørgen

Nystrup,

Jan-Helge

Larsen,

and

Ole

Risør.

Developing

Communication

Skills

for

the

General

Practice

Consultation

Process.

Sultan

Qaboos

University

Medical

Journal.

2010

December;

10(3):

318-325.

10.

Kurtz

S,

Silverman

J,

Draper

J:

Teaching

and

learning

communication

skills

in

medicine.

2nd

edition.

Oxon:

Radcliffe

publishing;

2005:58-62.

11.

General

Medical

Council.

Tomorrow's

Doctors:

Recommendations

on

Undergraduate

Medical

Education.

London:

GMC,

1993.

12.

Silverman

J,

Kurtz

S,

Draper

J:

Skills

for

Communicating

with

Patients.

Oxon:

Radcliffe

Medical

Press

Ltd;

1998.(Questionnaire)

13.

Abdulaziz

Al

Odhayani.

Teaching

communication

skills.

Canadian

Family

Physician.

2011

October;

57(10):

1216-1218.

14.

Suter

E,

Arndt

J,

Arthur

N,

Parboosingh

J,

Taylor

E,

Deutschlander

S.

Role

understanding

and

effective

communication

as

core

competencies

for

collaborative

practice.

Journal

of

Inter

professional

Care.

Jan

2009;23(1):41-51.

15.

Fryer-Edwards

K,

Arnold

RM,

Baile

W,

Tulsky

JA,

Petracca

F,

Back

AL:

Reflective

teaching

practices:

An

approach

to

teaching

communication

skills

in

the

small

group

setting.

Acad

Med

2006;81:638-644.

16.

Vicki

A.

Jackson,

M.D.,

M.P.H.

Anthony

L.

Back,

M.D.

Teaching

Communication

Skills

Using

Role-Play:

An

Experience-Based

Guide

for

Educators.

JOURNAL

OF

PALLIATIVE

MEDICINE.

Volume

14,

Number

6,

2011

17.

Mavis

B.

Self-efficacy

and

OSCE

performance

among

second

year

medical

students.

Adv

Health

Sci

Educ.

2001;6(2):93-102.

18.

Firdous

J,

Naeem

S,

Mark

N,

Najam

S,

Rizwan

Q.

Comparison

of

student's

self-assessment

to

examiners

assessment

in

a

formative

Observed

Structural

Clinical

Examination

(OSCE)

and

Correlation

between

cumulative

score

and

global

rating

scale

for

students

and

examiners

evaluation.

Journal

of

Postgraduate

Medical

Institute;

Vol

27,

No

1

(2012)

19.

Tor

Anvik,

Tore

Gude,

Hilde

Grimstad,

Anders

Baerheim,

Ole

B

Fasmer,

Per

Hjortdahl,

Are

Holen,

Terje

Risberg

and

Per

Vaglum.

Assessing

medical

students

'attitudes

towards

learning

communication

skills

-

which

components

of

attitudes

do

we

measure?

BMC

Medical

Education,

2007,

7;

4.

20.

Jette

A

,Janus

L

T,

Dorte

E

J,

René

H

,Anne

L

Ø,

Poul-Erik

K.

Comparison

of

the

medical

students'

perceived

self-efficacy

and

the

evaluation

of

the

observers

and

patients.

BMC

Medical

Education

2013,

13:49

doi:10.1186/1472-6920-13-49

21.

Back

AL,

Arnold

RM,

Baile

WF,

Fryer-Edwards

KA,

Alexander

SC,

Barley

GE,

Gooley

TA,

Tulsky

JA:

Efficacy

of

communication

skills

training

for

giving

bad

news

and

discussing

transitions

to

palliative

care.

Arch

Intern

Med

2007;167:453-460.

22.

Blanch-Hartigan

D:

Medical

students'

self-assessment

of

performance:

results

from

three

meta-analyses.

Patient

Educ

Couns

2011,

84:3-9.

23.

Kaufman

DM,

Laidlaw

TA,

Langille

D,

Sargeant

J,

MacLeod

H:

Differences

in

medical

students'

attitudes

and

self-efficacy

regarding

patient-doctor

communication.

Acad

Med

2001,

76:188.

24.

Oliver

D.

Teaching

medical

learners

to

appreciate

"difficult"

patients.

Canadian

Family

Physician.

2011;57:506-8.

e148-50.

25.

Bokken

L,

Linssen

T,

Scherpbier

A,

van

der

Vleuten

C,

Rethans

JJ.

Feedback

by

simulated

patients

in

undergraduate

medical

education:

a

systematic

review

of

the

literature.

Med

Educ.

2009;43(3):202-210.

26.

Eva

KW,

Regehr

G:

Self-assessment

in

the

health

professions:

a

reformulation

and

research

agenda.

Acad

Med

2005,

80:S46-S54.

27.

Eva

KW,

Regehr

G.

Knowing

when

to

look

it

up:

A

new

conception

of

self-assessment

ability.

Academic

Medicine.

2007;

82(10

suppl):S81-S84.

28.

Chur-Hansen

A.

The

self-evaluation

of

medical

communication

skills.

Higher

Ed

Res

Devel

2001;20:

71-9.

29.

Mattheos

N,

Nattestad

A,

Falk-Nilsson

E,

Attström

R.

The

interactive

examination:

Assessing

students'

self-assessment

ability.

Medical

Education.

2004;38(4):378-389.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|