Sodium

Stibogluconate treatment for cutaneous leishmaniasis:

A clinical study of 43 cases from the north of

Jordan

Mamoun

Mohammad Al-Athamneh

Hiathem Qasem Abu Al-haija

Ra'ed Smadi

Ayman S. Qaqaa

Heba Ajlouni

Correspondence:

Dr. Mamoun Al-Athamneh

Amman, Jordan

Mobile: 0962 777 903852

Email:

mamounathamnehh@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Objective:

to study the efficacy of Sodium Stibogluconate

intramuscular injections in the treatment

of cutaneous leishmaniasis, safety and

side effects.

Method: A total 43 patients were

seen over a period of 12 months, from

January 2009 to December 2010. All cases

were seen at Prince Rashed Military Hospital

in the north of Jordan. The diagnosis

of localized cutaneous leishmania was

made on clinical grounds proved by leishmania

smear or skin biopsy. The distribution

of patients according to gender, age groups,

time of the year, was made. The criteria

for sodium stibogluconate injection were:

the severity of symptoms, site of lesion

on face (ear, nose and cheek), and multiplicity

of lesions.

The dose of sodium stibogluconate given

was 10 mg\kg given as intramuscular injections

daily for total two weeks followed by

complete blood count, liver function test,

electrocardiogram as base line.

Results: 23 patients were males

and 20 were females (16 of them were 14

years and below). The age group ranged

from 2-72 years. One patient (2.3%) had

resistant infection to sodium stibogluconate;

and an admission was for one patient (2,

3%) for a few days because of a picture

of Hepatotoxicity. 42 patients showed

improvement of the lesion (98%); improvement

is defined when the lesion flattens and

ulceration disappears.

One patient (2.3%) demonstrated increase

in liver enzymes after one week of treatment'

upon stopping treatment for one week the

patient then resumes treatment with no

complications and with complete remission.

Conclusion:

Many cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis are

seen in Jordan causing cosmetic problems.

Early introduction of systemic anti-leishmania

agent is recommended. Sodium stibogluconate

is an effective way to decrease scarring

and dispigmentation, with minimum side effects.

Key words: cutaneous leishmania,

sodium stibogluconate, scar |

Leishmaniasis is a widely distributed disease

with both visceral and cutaneous manifestations.

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common form

of this disease. It has an annual incidence of

1 to 1.5 million cases. 90% of cases are reported

in just six countries, Afghanistan, Brazil, Iran,

Peru, Saudi Arabia and Syria (1).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis causes three distinct

clinical entities: localized cutaneous leishmaniasis

(a few lesions), diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis

(large number of lesions), muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis

(involving mucus membrane like nose, mouth,

larynx). Other leishmania species may attack

viscera causing visceral leishmaniasis or kala-azar

(1,2).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is divided into: the

Old World and new world leishmaniasis (3). Old

world leishmaniasis is due to L. major (zoonotic

cutaneous leishmaniasis which tends to heal

within 2-4 months), L. tropica (anthroponotic

tends to heal 6-15 months), L. aethiopica and

to L. infantum, which is responsible for all

the cutaneous disease in the northern Mediterranean

region and for some of the disease in North

Africa.

In the New World, localized cutaneous leishmaniasis

is caused mainly by L. peruviana, L. guyanensis,

L. braziliensis or L. mexicana species. Diffuse

cutaneous leishmaniasis is an infection caused

by L. aethiopica in Africa, and L. amazonensis

in South America. However, diffuse cutaneous

leishmaniasis is also observed in immunosuppressed

patients infected with species isolated commonly

in localized forms. Mucosal dissemination is

described in South America. It is caused by

L. braziliensis, and, less frequently by L.

panamensis or L. guyanensis(4).

Leishmania is highly contagious with at least

ninety percent attack rate among susceptible

individuals (5). Affecting children mainly,

usually lesions are at site of sandfly bites

on exposed areas like face (7).

Cutaneous leishmaniasis is a disfiguring disease

that normally resolves within 3 to 18 months

of initial infection. Treatment aims to cure

as well as prevent the development of more complex

manifestations like Muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis

and disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis (10).

This study was conducted to examine cutaneous

leishmania cases seen over a 12-month period,

taking into consideration patients' ages, the

time of occurrence during the year, the symptoms

and signs at presentation, the treatments given

and the complications encountered in affected

patients.

Forty three patients clinically diagnosed to have

cutaneous leishmaniasis were seen at Prince Rashid

Hospital over a period of 12 months (between January

2009 to December 2010). The distribution of patients

as regards the time of disease occurrence during

the year, sex and age group, were documented.

The diagnosis of cutaneous leishmania was established

on clinical grounds. Nodulo-ulcerative skin lesion,

with erythematous, violaceous, edematous edge

were the most common presenting features. Laboratory

investigations were carried out for all patients

and included leishmania smear to demonstrate Donovan

bodies, skin biopsy was done only if the lesion

was clinically suggestive but smear negative,

followed by routine and biochemical blood tests

including liver function test, ECG as base line.

All patients were given systemic sodium stibogluconate

intramuscular injections, 10 mg/kg per dose daily

for two weeks. The 1st injection was given in

the clinic with the availability of resuscitation

facilities to observe and interfere if anaphylactic

reaction developed, then patient completed the

course of injections at the nearest clinic. Patients

received instructions in regard to the nature

of disease and treatment options and to apply

topical antibiotics. All patients were re-examined

at follow up visit after two weeks to ensure complete

cure of the lesion.

Simple non-parametric statistical analysis was

made when necessary.

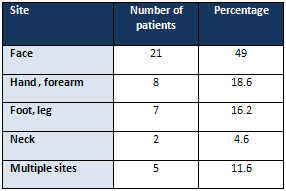

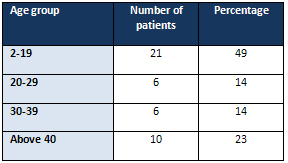

Twenty three patients (53.5%) were males and 20

patients were females (46.5%). The age ranged

from 2-72 years. The site of involvement in our

patients is shown in Table 1. The distribution

of patients according to age groups is shown in

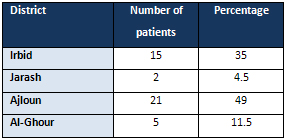

Table 2. The patients were from four districts,

Table 3. The face was commonly involved (49%)

: cheeks (39.2%), nose (18%), forehead (14.3%),

pinna (14.3%), lip (10.7), eyelid (3.5%).

Table 1: Site of involvements and their percentages

Table 2: The distribution of patients according

to age group

Table 3. The demographic distribution

One patient (2.3%) who was hospitalized, was 6

years old with three skin lesions on hand, neck

and ear and received 2 ml sodium stibogluconate

IM injections for one week and came to hospital

with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain. Liver function

test showed raised liver enzyme SGOT 1838, SGPT

1306 Alkaline phosphatase 316, the 2nd day after

cessation of therapy SGOT and SGPT dropped to

1314,741 respectively. WBC, PCV, PLATELET were

normal. PT, PTT, INR normal, abdominal U/S normal,

HBSAG, HC antibodies were negative. After 6 days

SGOT and SGPT dropped to 180 and 175 respectively;

lesions at these time showed 70% improvement.

One patient (2.3%) who had ulcerative nodule at

the lower lip, clinically consistent with Cutaneous

leishmania. Leishmania smear was negative but

biopsy confirmative, and patient received sodium

stibogluconate injection for one week and developed

a slight rise in liver enzyme, Patient was stopped

for one week and returned to normal resumption

of injections with no complications with complete

healing but with atrophic scar.

One patient (2.3%) received sodium stibogluconate

injections for two weeks but did not show clinical

improvement after completion of the course of

injections, and was given alternative treatment.

Leishmaniasis are a group of chronic

infections affecting human and other animal

species, belonging to flagellated protozoans

of the order kinetoplastidae, and transmitted

by the bite of sandflies of the genera phlebotomus

and lutzomyia (5). It is an obligate intracellular

parasite that presents in two forms: promastigote

in the gut of sandflies where it multiplies

and migrates to the proboscis and is introduced

to the host whether human, rodent, or other

animal species and immediately phagocytosed

by host phagocytes where it changed into amastigote(7).

It is considered to be a self- limiting disease

when localized to skin but always heals with

retracted scar and dispigmentation but some

may become chronic or disseminated(2).

In endemic areas like Jordan where transmission

is stable, children are especially affected.

Un our study children were affected in 37% of

the cases, as shown in Table 7, and the cumulative

rate of infection as determined by the presence

of scars and positive leishmanin tests may approach

100%.

The treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis depends

on the species of leishmania but identification

of the species by culture and isoenzyme is time

consuming. Also new techniques of DNA amplification

by polymerase chain reaction are not widely

available which makes treatment depend on the

geographical area and the epidemiology of the

disease; the main cause of cutaneous leishmania

in our area is leishmania tropica (5).

Cutaneous leshmaniasis is the primary infection

with one of the leishmania species starting

as a papule then increasing in size resulting

in a nodulo-ulcerative lesion, usually on exposed

areas at the site of sandfly bite (5). In our

study, there are 21 cases (49%) involving the

face, 8 cases (18.6%) involving the hand and

forearm, 7 cases (16.2%) involving the foot

and leg, 2 cases (4.6%) involving the neck,

5 cases (11.6%) involving multiple sites of

those mentioned above with no single case involving

a non-exposed area.

Ajloun district had the highest number of patients

simply because towns of Ajloun are geographically

appropriate for sandflies living and reproduction

regarding temperature and humidity.

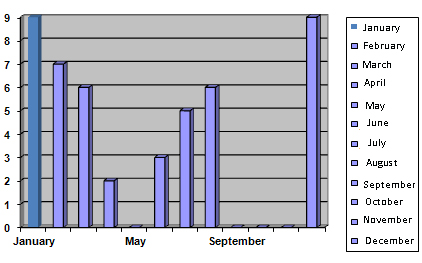

Our study shows the highest number of patients

in January and December then March (Figure 1),

and this may be due to rainy season in winter

with the formation of swamps which allow reproduction

and growth of sand flies which facilitate vector

transmission .

Figure 1: The distribution of patients according

to the time of year

Pentavalent antimonials are the mainstay treatment

for both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis

(8). Two forms are currently available: meglumine

antimoniate and sodium stibogluconate. The mechanism

for their effectiveness is not well understood,

but may involve inhibition of adenosine triphosphate

synthesis(9).

The face is affected in 49% of the cases; it

results in scarring and dispigmentation which

is disfiguring on the face.

It is generally recommended that anyone with

cutaneous leishmaniasis is to be treated with

systemic sodium stibogluconate (especially children

and when face is involved) because scar and

dispigmentation will be inevitable and disastrous.

Systemic antimonial decrease the size of the

lesion, there is no progression to ulceration

and results in less scarring, and rapid healing.

Therefore, we started all patients on sodium

stibogluconate injection for two weeks; 98%

showed complete cure of the lesion upon follow

up 2-3 months after completion of the course.

One of the most important side effects of sodium

stibogluconate is prolongation of QT interval

predisposing to arrhythmias, which are uncommon

when used in doses less than 20mg/kg and within

a period of less than 2 weeks (6). In our study

base line ECG was done excluding patients with

abnormal Electrocardiogram from the study; follow

up Electrocardiogram was done with no change.

Hepatotoxicity is another side effect of sodium

stibogluconate injection which is reversible

withen 6 weeks of cessation of treatment (6).

Base line liver function tests were done to

exclude any patient with liver disease from

the study; two patients developed increases

in liver enzyme which returned to normal within

two weeks of cessation of treatment.

Wide use of sodium stibogluconate in the treatment

of cutaneous leishmaniasis can result in the

emergence of a resistant strain(9). In our study

one patient did not show improvement clinically

after completion of the course of injections

(still the lesion was wet and increasing in

size). The mechanism for the development of

resistance is not well understood. It could

be an intrinsic difference in the species sensitivity

to these medications; another mechanism is the

efflux of a drug or its active derivative(9).

Studies showed that the addition of allopurinol

to the treatment regimen gave better results

regarding decrease of the size of the lesion

and clearance (4). In our resistant case just

when it showed no healing, a change to rifampicin

300mg daily for 2 weeks allowed healing of the

lesion.

In addition, there are several alternative treatment

options available; local infiltration with sodium

stibgluonate of the whole lesion intradermally

with 2-3ml every week until 4 weeks (4). Also

Oral zinc sulphate (5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks)

showed promising results in a recent Indian

trial (8).

Cryotherapy using liquid nitrogen is a well

known option for treatment in the middle east

including Jordan where 2-3 sessions for 20-30

seconds freezing (one month interval) resulted

in healing of most of the lesion but with a

different degree of atrophic scar and dispigmentation.

But when multiple lesions, large lesions, over

the joint, are on the face, the cosmetic unit

usually tries to avoid cryotherapy.

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis is cosmetically disfiguring

and slowly growing skin lesions are not fatal

but occasionally can result in significant morbidity

especially when present on the face.

Early treatment with systemic antimonial agent

is essential in the adults and children to prevent

or decrease the risks of complication like: scarring

and dispigmentation.

We believe that it is highly recommended to give

systemic sodium stibogluconate injection to all

patients with Cutaneous leishmaniasis, especially

when certain areas like ear, eyelid, lip, cheek,

nose, and multiple lesions are present.

1. World health organization

(WHO). Leishmaniasis:

background information

. A brief history of disease

.WHO. 2009. available

from: www.WHO.int\leishmaniasis.

2. Omar Lupi. Protozoa

and worms. In: bolongia

dermatology 2nd Ed.2008.p.1263-1265.

3. Blum J, Desjeux P,

Schwartz E, Beck B, Hatz

C. Treatment of cutaneous

leishmaniasis among travellers.

J Antimicrob Chemother

2004; 53:158-66.

4. Philippe Minodiera,

Philippe Parolab. Cutaneous

leishmaniasis treatment.

Travel Medicine and Infectious

Disease (2007) 5, 150-158(review

article free online).

5. Barbara L. Herwaldt.

Leishmaniasis. In: Kasper

DL (Editor-In-Chief).

Harrison's principles

of internal medicine.

16th Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill

Companies, Inc. 2005.

p. 1233-1236.

6. Wise ES, Armstrong

MS, Watson J, Lockwood

DN. Monitoring Toxicity

Associated with Parenteral

Sodium Stibogluconate

in the Day-Case

Management of Returned

Travellers with New World

Cutaneous Leishmaniasis.

PLoS Negl Trop Dis 6(6):

e1688. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd2012

(free online).

7. Wolff, Klaus; Goldsmith,

Lowell A. Leishmaniasis

and other protozoan infections.

In: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology

in General Medicine, 7th

Edition. McGraw-Hill,

Inc. 2008. ch. 206

8. J.A.A. Hunter, J.A.

Savin, M.V. Dahl. Leishmaniasis.

In: Clinical dermatology.

3rd Ed.2003.p.201-202.

9. Arun Kumar Haldar,

Pradip Sen, and Syamal

Roy .Use of Antimony in

the treatment of Leishmaniasis:

Current Status and Future

Directions. Review Article.

Molecular Biology International

at: http://dx.doi.org/10.4061/2011/571242.2011.

10. Tracy Garnier &

Simon L Croft. Topical

treatment for cutaneous

leishmaniasis.

Department of Infectious

and Tropical Diseases,

London School of Hygiene

& Tropical Medicine.

Email: simon.croft@lshtm.ac.uk

,Current Opinion in Investigational

Drugs 2002 3(4):

|