|

Medical Education and

the Practice of Medicine in the Muslim countries

of the Middle East

Lesley Pocock

Mohsen Rezaeian

Correspondence:

Lesley Pocock

Publisher - medi+WORLD International

Australia

Email: lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

|

Abstract

and Overview

Recorded history shows the ancient countries

and populations of the Middle East were

among the first in the world to teach

and practice the science of medicine,

and from the region, it spread to the

rest of the known world.

This paper provides

firstly a history of the regional development

of the science of medicine followed by

a brief snapshot of current regional medical

education and research, to see if it is

matching the needs of the people of the

region, and reaching and setting the same

high standards as it did centuries ago.

|

The Middle East region was not just the cradle

of civilisation, the place where humans stopped

their nomadic hunting and gathering, and started

to form towns and cities and complex cultures,

it was also where some of the more complex sciences

and arts were first practised and recorded.

Historical records show that the practice of

medicine occurred in the early history of Egypt,

Persia, Mesopotamia, China, India, Greece and

the city of Rome, before the third century AD

(1).

In the history of the Middle East the practice

of medicine was first recorded in Persia (Iran).

The Vendidad, a surviving collection of texts,

devotes many chapters to the practice of medicine.

One of these texts describes three kinds of

medicine: medicine by the knife (surgery), medicine

by herbs (pharmacology), and medicine by divine

words (counselling or placebo) (1, 2).

An encyclopaedia of medicine in Pahlavi literature

listed 4,333 diseases (1, 2).

The city of Gondi-Shapur in Persia (226 to

652 AD) had the first institution we would recognise

as a modern day hospital and academic centre

of learning. These institutions were called

bimarestan, a Persian word for ‘a place

for the sick,’ and as well as providing

medical services they also retained patients’

medical records (1-6).

The academy of Gondi-Shapur was established

between 309 to 379 AD and consisted of a university,

a library and a teaching hospital. Similar to

modern academic medicine the bimarestan of Gondi-Shapur

were a place where medical students worked in

the hospital under the supervision of a medical

faculty. There is evidence that the graduates

had to then pass an examination in order to

practice as accredited physicians (1).

After the Arabs conquered Persia in 638 AD,

Gondi-Shapur became the Arabian School of Medicine.

The entire system was gradually transferred

to Baghdad, where it became known as the ‘Golden

Age of Islamic Medicine’ (1).

The philosophy behind this Golden Age of universal

healthcare was the Islamic belief in the Qur’an

and Hadiths, which stated that Muslims had a

duty to care for the sick (3-6). In the Islamic

Age such hospitals were paid for through charitable

donations. They were founded as early as the

8th Century and eventually were set up across

the entire Islamic world (3-6). The hospitals

also provided free medical services to the poor

and sent physicians and midwives into rural

areas. Some hospitals provided early ‘specialist

services’ such as midwifery and care for

lepers and the disabled (3-6).

Al-Razi, (850 - 923), of Persia, was an early

medical researcher. He produced over 200 books

about medicine and philosophy, including a book

where he compiled all known medical knowledge

in the Islamic world. This book was translated

into Latin and was the basis of the early western

medical education system (4).

Al-Razi, also initiated scientific methods

promoting experimentation and observation. He

wrote on the relationship between doctor and

patient, believed in a holistic approach to

medicine and was instrumental in early ‘history

taking,’ not just of the medical background

of the patient but also the patients’ family

members. He advanced medical diagnosis through

looking for the cause of the symptoms (4-6)

and described human physiology and understood

how the brain and nervous system worked (4-6).

In 14th century Persia, the book Tashrih al-badan

(Anatomy of the body), was written by Mansur

ibn Ilyas (c. 1390), and contained an early

Atlas of Anatomy with diagrams of the body’s

structural, nervous and circulatory systems

(4-6).

Human

history

has

seen

the

rise

and

fall

of

many

Empires,

Kingdoms

and

regions.

The

entropy

that

pervades

matter

on

the

micro

scale

seems

to

also

work

on

the

macro

scale

and

while

we

will

not

look

at

the

philosophical

or

psychosocial

reasons

for

these

cycles

in

this

article,

the

glorious

past

of

the

Middle

East

region

is

now

undergoing

some

needed

revival

in

these

scholarly

disciplines.

The

Islamic

religion

fostered

early

the

view

of

medicine

as

a

science

to

be

learned

and

understood,

as

well

as

the

concept

of

parity

of

healthcare

for

all

members

of

society,

(universal

healthcare)

irrespective

of

the

patient’s

ability

to

afford

it.

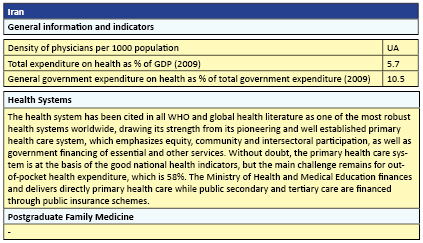

This

spirit

lives

on

in

the

universal

health

systems

most

Middle

Eastern

countries

have

adopted,

particularly

in

Iran,

which

the

WHO

describes

as

one

of

the

most

robust

health

systems

worldwide,

drawing

its

strength

from

its

pioneering

and

well

established

primary

health

care

system,

which

emphasizes

equity,

community

and

intersectoral

participation,

as

well

as

government

financing

of

essential

and

other

services

(7).

As

well

as

University

based

medical

schools

most

regional

countries

now

have

postgraduate

colleges

to

focus

on

standards

and

ongoing

medical

education

to

support

and

address

the

needs

of

practising

doctors

and

specialists.

The

region

hosts

many

international

medical

conferences

and

quite

a

few

overseas

universities

have

set

up

campuses

in

the

region.

Some

Universities

that

have

recently

re-appraised

their

focus

and

customs

are

high

in

the

list

of

the

top

universities

in

the

world,

(e.g.

Aga

Khan

University

and

Hospital

in

Karachi,

Lahore

University

of

Management

Sciences,

and

Sharif

University

in

Iran)

(2).

Many

countries

have

ongoing

medical

education

programs,

in

the

form

of

Continuing

Medical

Education

(CME)

and

Continuing

Professional

Development

(CPD)

e.g.

UAE,

Jordan,

Turkey

and

Lebanon.

Generally

however,

and

additional

to

the

march

of

time

from

the

glorious

days

of

the

past,

a

multitude

of

factors

has

led

to

various

problems

in

most

countries

of

the

region.

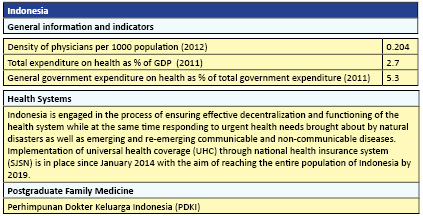

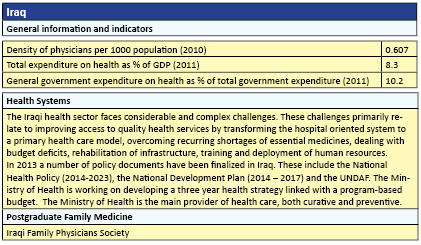

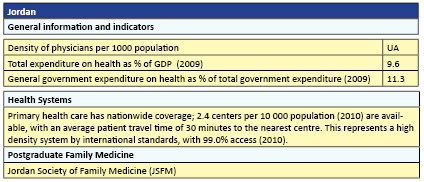

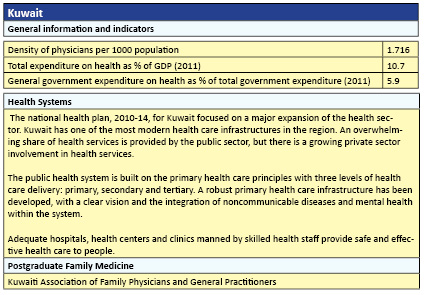

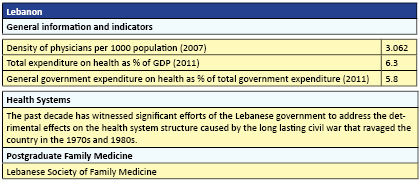

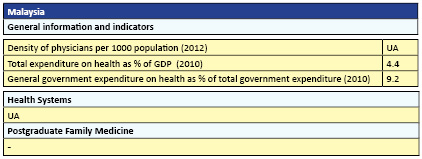

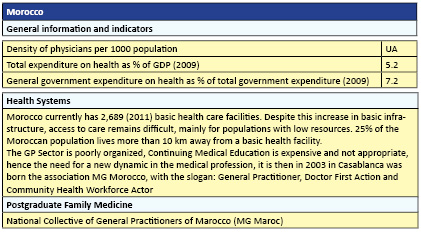

Before

discussing

these

factors,

the

following

provides

a

snapshot

of

the

main

features

of

the

health

and

medical

education

status

of

each

major

Middle

East

country

compared

with

some

non-regional

Muslim

countries,

Malaysia

and

Indonesia.

The

practice

of

medicine

is

to

ultimately

address

the

current

health

needs

of

a

population,

through

medical

education

and

training,

research

and

public

health

policies,

along

with

affordable

healthcare.

The

people

of

the

Middle

East

now

face

much

the

same

disease

states

as

the

rest

of

the

developed

world

and

medical

education

and

health

policy

must

now

meet

these

changing

needs.

The

change

of

lifestyles

in

the

Middle

East

and

elsewhere

has

introduced

a

new

range

of

disease

states,

particularly

those

of

a

cardiovascular

nature

(e.g.

diabetes

and

heart

disease).

This

in

turn

has

necessitated

a

change

of

both

health

priorities

and

educational

focus.

In

the

Middle

East

and

North

Africa

region,

incidence

of

non-communicable

diseases

such

as

heart

disease

are

up

by

44%,

stroke

up

by

35%,

and

diabetes

up

87%

since

1990

and

these

diseases

are

causing

more

premature

death

and

disability

than

they

did

in

the

past

(9).

The

region

has

succeeded

in

reducing

disease

burden

from

many

communicable,

newborn,

nutritional,

and

maternal

conditions.

However,

lower

respiratory

infections,

remain

the

second

leading

cause

of

healthy

years

lost

in

the

region

(9).

Aging

populations

and

longevity

add

another

dimension

to

economic

burden,

and

new

diagnostic

equipment,

techniques

and

therapeutics

have

created

higher

expectations

of

successful

medical

outcomes

in

patient

populations.

At

the

same

time

these

innovations

have

greatly

increased

the

cost

of

both

medical

education

and

delivery

of

universal

health

care.

This

also

applies

to

the

cost

of

medicines,

particularly

highly

priced

pharmaceutical

products,

with

many

nations

of

the

world

now

having

to

subsidise

their

high

costs

to

make

them

available

to

their

patient

populations.

At

the

same

time,

poorer

countries

in

the

region,

including

Yemen,

Djibouti,

and

Iraq,

continue

to

struggle

with

a

high

burden

from

infectious

diseases

(9).

Among

the

Muslim

countries

in

the

region,

the

leading

causes

of

disease

burden

range

from

preterm

birth

complications

in

Algeria

and

Palestine,

depression

in

Jordan,

and

ischemic

heart

disease,

or

coronary

artery

disease,

in

Egypt,

Iran

and

Lebanon

(9).

When

comparing

rates

of

diseases

and

injuries

across

countries

in

the

Middle

East

and

North

Africa

and

taking

into

account

differences

in

population

growth

and

ages,

Lebanon,

Syria,

and

Tunisia

performed

best

relative

to

other

countries

in

the

region

while

Iraq,

Yemen,

and

Djibouti

performed

the

worst

(9).

In

places

such

as

Palestine

(and

currently

Syria,

Iraq,

and

Libya)

even

greater

burdens

of

war

are

placed

on

health

systems

that

are

being

destroyed

and

made

ineffective.

It

seems

it

may

even

now

be

policy

to

deliberately

target

doctors

and

hospitals

to

demoralise

such

communities.

Climate

change

and

environmental

problems,

often

exacerbated

by

war

or

government

dysfunction,

(e.g.

no

collecting

of

waste,

scarcity

and

quality

of

clean

drinking

water,

air

pollution)

contribute

to

the

picture

as

does

an

upsurge

in

road

accidents.

There

is

need

for

specific

public

health

promotion

to

limit

lifestyle

disease

and

poor

health

habits

such

as

cigarette

smoking

and

drug

taking

as

well

as

addressing

mental

health

issues

such

as

the

rising

incidence

or

diagnosis

of

depression.

Refugees

within

the

region

bring

their

own

set

of

problems

–

not

just

in

additional

healthcare

needs

but

sequelae

of

war:

malnutrition,

injuries,

mental

health

issues,

overcrowded

conditions

and

disease

risk.

Current

regional

Medical

Education

does

not

always

match

or

meet

the

high

principle

of

universal

healthcare.

Varying

standards

of

education

within

the

region

often

result

in

new

regional

graduates

unable

to

find

employment,

or

even

qualify

for

employment

in

the

region.

At

the

same

time

well

educated

doctors

are

often

poached

by

overseas

employers

who

can

offer

greater

financial

returns.

Conversely

some

Middle

East

countries

preferentially

hire

overseas

doctors

and

nurses

to

meet

their

own

internal

needs

putting

a

greater

burden

on

health

systems.

The

opportunities

for

higher

levels

of

research

and

publication

can

also

be

lacking

in

the

region.

Most

countries

of

the

Middle

East,

and

Muslim

countries

generally

do

now

endeavour

to

provide

universal

healthcare

but

with

varying

success.

It

must

be

said

that

most

countries

of

the

world

have

now

also

adopted

the

principle

of

universal

healthcare

but

with

some

notable

exceptions,

even

among

developed

countries.

The

reasons

why

the

Universities

are

not

providing

adequately

trained

doctors

to

meet

the

needs

of

the

regions’

medical

hiring

organisations

are

complex

and

may

differ

from

country

to

country.

Governments,

academics

and

administrators

of

regional

universities

will

need

to

address

any

deficiencies

in

their

curricula

and

postgraduate

institutions.

The

Organisation

of

Islamic

Cooperation

(OIC)

in

its

Report

of

29

October

2015

recommended

that

governments

must

give

universities

more

autonomy.

Professors

need

to

be

free

to

teach

topics

that

are

not

tightly

regulated

by

ministries

(2).

Universities

need

to

also

be

free

from

political

or

religious

opinion

or

influence.

There

is

precedent.

In

Pakistan,

two

private

universities

established

in

the

1980s,

the

Aga

Khan

University

and

Hospital

in

Karachi

and

Lahore

University

of

Management

Sciences,

revolutionized

medical

and

business

education

within

a

decade

of

their

creation.

Students

elsewhere

began

demanding

the

standard

set

by

these

educational

pioneers

(2).

The

OIC

report

found

that

the

Muslim

countries

on

average

invest

less

than

0.5%

of

their

gross

domestic

product

(GDP)

on

research

and

development

(R&D).

Students

in

the

Muslim

world

who

participate

in

standardized

international

science

tests

perform

below

the

standards

of

their

peers

worldwide,

and

the

situation

seems

to

be

worsening

(2).

An

obvious

reason

for

this

however

may

be

a

non-standardised

curriculum.

The

OIC

recommend

that

Universities

in

OIC

nations

need

to

be

granted

more

autonomy

to

transform

themselves

(2).

University

science

programmes

are

often

found

to

be

using

restricted

content

and

outdated

teaching

methods.

The

OIC

report

also

stated

scientific

research

must

be

relevant

and

responsive

to

society’s

intellectual

and

practical

needs

and

students

must

receive

a

broad,

liberal

education.

Some

basic

scientific

facts

are

still

seen

as

controversial,

and

marginalized

e.g.

evolution

(2).

Another

problem

is

that

faculty

members

rarely

receive

any

training

or

evaluation

in

pedagogy.

In

many

OIC

universities,

didactic

teaching

methods

persist

(2).

In

many

universities,

curriculum

changes,

faculty

appointments

and

promotions

are

dictated

by

governments

Ministries

of

Health

and

other

agents.

The

57

countries

of

the

Muslim

world

that

are

a

part

of

the

Organisation

of

Islamic

Cooperation

(OIC)

are

inhabited

by

nearly

25%

of

the

world’s

people.

But

as

of

2012,

they

had

contributed

only

1.6%

of

the

world’s

patents,

6%

of

its

academic

publications,

and

2.4%

of

the

global

research

expenditure

(2).

The

number

of

scientific

papers

they

produce

remains

below

the

average

of

countries

with

similar

GDP

per

capita.

A

few

institutions

attempt

to

relate

their

students’

learning

to

their

cultural

backgrounds

and

contemporary

knowledge.

The

Times

Higher

Education

world

university

rankings

named

Sharif

University

as

the

top

Iranian

university

and

number

eight

in

the

OIC

(10).

Habib

University,

in

Pakistan,

also

follows

the

same

model.

Textbooks

are

often

imported

from

outside

the

region.

Although

of

a

high

standard,

they

assume

a

Western

undergraduate

experience

and

are

written

in

English

or

French

(2).

Having

English

as

the

standard

international

medical

and

scientific

language

disadvantages

students

from

all

countries

that

are

not

native

English

speakers.

The

heavy

requirements

on

academics

to

publish

whether

there

is

research

of

any

importance

or

repute

occurring

in

their

institution

or

if

there

is

anything

of

significant

merit

to

report

or

not,

can

also

cause

problems.

There

should

be

less

emphasis

on

meeting

quotas,

and

more

on

quality

and

the

merit

of

publishing

particular

research

or

study

(11).

This

also

applies

worldwide.

While

it

is

necessary

to

acknowledge

the

workload

and

academic

pressure

during

medical

training

there

should

also

be

time

and

budgets

allocated

for

meaningful

research

and

publication

(10,

11).

Quality

academics

themselves

need

to

be

properly

salaried

and

remunerated.

Regional

medical

journals

are

assisting

young

researchers

and

academics

(10,

11)

A

healthy

national

medical

education

consists

of

both

tertiary

and

postgraduate

medical

education

institutions.

It

is

well

recognised

these

days,

especially

in

times

of

great

change,

that

education

does

not

stop

once

the

graduate

goes

into

practice

(lifelong

learning).

Not

only

are

there

new

developments

and

techniques,

new

therapeutics

and

new

diagnostic

equipment

at

the

primary

care

population

level,

we

have

seen

the

emergence

of

quite

a

few

new

diseases

(e.g.

Ebola)

and

mutations

of

existing

diseases

(e.g.

Zika).

There

is

also

place

and

requirement

for

the

practising

doctor

to

contribute

to

ongoing

knowledge

regarding

emergence

and

epidemiology

of

emerging

and

mutating

viral

diseases

(15).

Socio-economic

and

psychosocial

issues

affecting

the

practice

and

delivery

of

medicine

can

and

do

vary

from

nation

to

nation.

It

is

no

longer

good

enough

to

‘keep

your

eye’

on

the

medical

journals;

doctors

need

a

consistent

approach

to

ongoing

medical

education.

Many

postgraduate

medical

colleges

have

brought

in

firstly,

Continuing

Medical

Education

(CME),

then

Continuing

Professional

Development

(CPD),

with

the

latter

a

step

ahead

in

that

it

is

no

longer

good

enough

to

know

‘what’s

new’,

doctors

need

to

evaluate

new

information

and

know

if,

when

and

why

they

should

introduce

it

into

practice.

It

is

not

acceptable

to

put

patients

on

a

new

therapy

unless

doctors

are

sure

it

works

in

all

patients

and

all

situations

and

if

its

trials

have

been

sufficient

in

time,

enrolled

numbers

and

efficacy

and

with

no

longterm

adverse

effects

on

patients.

QA&CPD

(Quality

Assurance

and

Continuing

Professional

Development)

was

brought

in

to

provide

a

level

of

science

(and

mathematics)

to

CME/CPD.

Postgraduate

Education

Providers

need

to

know

and

be

able

to

show

that

the

doctor-student

has

indeed

learned

something

(accurate)

from

their

post

graduate

education

and

that

the

education

they

provide

to

the

doctors

has

done

its

job

at

the

level

of

patient

care.

There

also

needs

to

be

someone

to

ensure

the

quality

of

postgraduate

continuing

education

and

this

is

usually

done

by

the

Postgraduate

College

or

Academy

testing

and

training

and

evaluating

postgraduate

education

providers,

be

they

tertiary

colleges,

universities,

a

medical

society,

or

independent

providers.

Finally

Quality

Improvement

(QI)

has

become

the

current

norm.

The

doctor

undergoing

postgraduate

CME/CPD

has

to

now

show

that

the

postgraduate

education

has

brought

Quality

Improvement

into

their

practice.

There

are

many

ways

to

go

about

this

–

even

though

they

require

a

bit

of

subjective

evaluation

on

the

part

of

the

practising

doctor.

To

enforce

Quality

Assurance

(QA)

and

Lifelong

learning

as

part

of

regular

practice,

it

has

become

a

requirement

for

maintaining

ongoing

Professional

Vocational

Registration

(VR)

in

some

countries.

The

Vocational

Registration

requirement

approach

can

however

be

punitive

to

the

patient

populations

if

there

are

not

enough

doctors

practising

(quality

assured

or

not)

-

on

the

assumption

that

those

practising

have

some

basic

skills.

In

countries

greatly

lacking

in

doctors

another

aim

of

CME

should

be

to

improve

the

skills

of

doctors

already

in

practice.

Some

of

the

first

family

medicine

programs

in

the

region

occurred

in

Turkey

in

1961,

in

Bahrain

in

1978,

in

Lebanon

in

1979,

in

Jordan

in

1981,

and

in

Kuwait

in

1983.

Family

medicine

programs

have

also

been

established

in

Qatar,

the

United

Arab

Emirates,

Libya,

and

Iraq.

In

most

programs,

family

medicine

training

occurs

mostly

in

hospitals,

even

though

few

Middle

Eastern

family

physicians

practice

in

hospitals

on

completion

of

residency

training.

Thus,

there

is

a

need

for

better

outpatient

training,

but

resistance

from

those

responsible

for

traditional

medical

education

can

make

it

difficult

to

change

the

current

model.

There

is

need

for

better

opportunities

for

professional

development

after

graduation

and

for

establishing

research

activities

in

family

medicine

(12).

Financing

the

medical

education

and

health

sector

is

an

increasing

national

burden

and

involves

major

and

obvious

considerations

–

good

coordinated

governance

across

all

sectors,

national

wealth

and

development

being

the

most

obvious.

Some

Middle

East

countries

have

a

‘patronage’

system

whereby

institutions

need

to

continually

apply

for

separate

items

of

funding

preventing

them

to

some

degree

from

being

able

to

plan

ahead

and

invest

in

necessary

infrastructure.

Overseas

universities

have

also

set

up

in

the

region

and

thus

provide

their

own

curricula

and

own

education

and

their

graduates

often

then

proceed

to

practice

overseas.

It

does

however

allow

those

employers

seeking

‘western

trained

doctors’

to

employ

graduates

from

the

region.

Regular

and

ongoing

funding

and

sufficient

levels

of

funding

are

needed

to

ensure

that

each

country

produces

sufficient

numbers

of

doctors

to

adequately

care

for

population

health.

Political

will

and

allocation

of

government

budgets

is

tied

together.

Of

course

investing

in

tertiary

education

facilities

and

professional

staffing,

needs

to

also

be

weighted

against

the

potential

student

population.

Small

populations

on

a

pro

rata

basis

require

heavier

financial

commitments.

While

the

principles

and

practice

of

‘universal

healthcare

for

all’

is

well

championed

in

the

Middle

East

region

there

seems

to

be

need

for

improvement

in

the

quality

and

availability

of

undergraduate

and

ongoing

medical

education

to

meet

the

ongoing

needs

and

expectations

of

the

populations

of

each

country.

This

may

need

a

review

of

numbers

entering

the

education

system

as

well

as

the

curriculum

in

medical

schools,

to

ensure

they

meet

all

population

health

needs.

There

is

discrepancy

between

health

planning

and

the

application

in

practice

(14).

In

most

countries

the

medical

education

system

is

not

producing

enough

primary

care

doctors,

or

to

the

standards

now

required

by

the

region

and

the

world.

The

health

care

system

still

tends

to

be

specialist

orientated.

It

is

well

accepted

globally

that

primary

care

is

the

optimum

approach

for

cost

effective

healthcare

for

all

(14).

Keeping

patients

out

of

the

hospital

system

and

the

more

expensive

specialist

system

reduces

national

health

costs

and

saves

those

services

for

the

patients

who

really

need

them.

There

needs

to

be

a

coordinated

governance

system

looking

at

all

sectors

and

making

sure

they

work

together

in

an

efficient

and

complementary

fashion.

Medical

schools

should

meet

three

criteria,

i.e.

educating

medical

students

in

sufficient

numbers

to

quality

international

standards

to

meet

national

requirements

and

needs,

conducting

research,

and

being

a

community

advocate

for

national

and

regional

health

and

medical

issues

and

ensuring

curriculum

meets

these,

and

thirdly,

providing,

via

suitably

educated

graduates,

health

and

medical

care

to

all

members

of

society

based

on

ethical

guidelines.

Medical

schools

should

consider

the

needs

of

the

communities

which

they

serve

and

deliver

their

services

based

on

socially

and

culturally

acceptable

criteria

(13).

It

is

incumbent

on

governments

to

make

the

necessary

financial

allocations

to

the

education

sector

and

to

secure

ongoing

budgets

to

allow

them

to

plan

for

the

future.

The

more

money

spent

on

ensuring

a

fit

and

proper

medical

education

and

health

delivery

system,

the

less

money

spent

later

on

public

health

needs.

In

turn,

universities

and

medical

schools

must

seek

to

contain

the

costs

of

education

and

educate

students

on

cost

effective

treatment

and

processes

of

care.

A

socially

accountable

medical

school

provides

its

services

based

on

the

criteria

of

cost-effectiveness,

relevance,

equity

and

high

quality

(13).

One

process

however

may

not

necessarily

meet

the

specific

needs

of

all

communities

or

nations,

and

it

is

incumbent

on,

firstly,

governments

and

health

administrators

to

plan

national

needs

and

then

have

the

education

systems

capable

of

producing

the

trained

medical

professionals

to

meet

those

needs.

Universities

and

medical

schools

need

to

meet

these

challenges

with

the

appropriate

curriculum

and

processes

if

they

are

to

remain

viable

and

relevant

to

community

needs.

1.

Journal

of

Perinatology

(2011)

31,

236–239.

2011

Nature

America,

Inc.

0743-8346/11

2.

Nidhal

Guessoum,

Athar

Osama.

Revive

universities

of

the

Muslim

world.

Nature,

Vol.

5

2

6,

2

9

October

2

0

1

5

3.

Medicine

in

the

medieval

Islamic

world

-

Wikipedia,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medicine_in_the_medieval_Islamic_world

4.

Islamic

Medicine

-

History

of

Medicine

-

Explorable.com.

https://explorable.com/islamic-medicine

5.

Royal

Society.

A

New

Golden

Age?

The

Prospects

for

Science

and

Innovation

in

the

Islamic

World

(Royal

Society,

2010).

6.

Royal

Society.

The

Atlas

of

Islamic

World

Science

and

Innovation

(Royal

Society,

2014).

7.

WHO

Country

Profiles.

http://www.who.int/countries/en/)

8.

Global

Family

Doctor

-

WONCA

Online;

www.globalfamilydoctor.com/

9.

The

World

Bank

/

IHME:

In

Middle

East

and

North

Africa,

Health

Challenges

are

Becoming

Similar

to

Those

in

Western

Countries.

2013

10.

Research

participation

among

medical

trainees

in

the

Middle

East

and

North

Africa

Ahmed

Salem,

Sameh

Hashem,

Layth

Y.I.

Mula-Hussain,

Ala’a

Nour,

Imad

Jaradat,

Jamal

Khader,

Abdelatif

Almousa

11.

Rezaeian

M,

Pocock,

L.

Plagiarism

and

Self

plagiarism

from

the

perspective

of

academic

authors.

MEJFM

May

2016

-

Volume

14,

Issue

4

12.

Abyad

A1,

Al-Baho

AK,

Unluoglu

I,

Tarawneh

M,

Al

Hilfy

TK.

Development

of

family

medicine

in

the

middle

East.Fam

Med.

2007

Nov-Dec;39(10):736-41.

13.

Rezaeian,

M.

Pocock,

L.

Social

accountability

-

a

challenge

for

global

medical

schools.

World

Family

Med

J.

2011;

9

:15-19.

14.

Cayley

Jr

WE,

Pocock

L,

Inem

V,

Rezaeian,

M.

Global

Competencies

in

Family

Medicine.

World

Family

Med

J.

2010;

8

:19-32.

15.

Pocock

L,

Rezaeian

M.

Virology

vigilance

-

an

update

on

MERS

and

viral

mutation

and

epidemiology

for

family

doctors.

Middle

East

J

Family

Med.

2015;

13(5)

:52-59.

|