This

cross-sectional

study

has

been

approved

by

Hamad

Medical

Research

Centre

under

research

No.

10014/10.

There

are

22

primary

health

care

(PHC)

centres

in

Qatar.

Of

these

centres,

16

centres

have

diabetic

clinics

providing

specialized

diabetic

services

where

a

qualified

family

physician

and

a

senior

nurse

who

have

been

trained

and

certified

as

diabetic

educators

help

in

providing

health

education

and

document

all

the

diabetes

related

data

in

a

diabetes

follow-up

sheet

which

is

supervised

and

signed

by

the

attending

physician;

so

this

study

was

targeting

Arab

Diabetic

patients

attending

primary

health

care

diabetic

clinics.

We

have

used

a

two

stage

random

sampling

where

we

have

selected

8

health

centres

out

of

16

(4

in

Doha,

the

capital

cities

and

another

4

from

other

towns).

Then

459

Diabetic

patients

of

18

years

of

age

or

older

,

with

type

1

or

type

2

diabetes

who

were

Qataris

or

any

other

Arab

nationals

have

been

recruited

through

random

sampling

by

selecting

three

days

of

the

week

and

selecting

all

diabetic

patients

attending

the

clinics.

We

have

excluded

all

women

with

gestational

diabetes,

and

those

without

a

medical

record

in

the

health

centre.

An

informed

consent

form

has

been

taken

from

each

patient

who

accepted

to

be

recruited

in

this

study.

The

primary

outcome

was

PM

which

can

be

defined

as

depression,

anxiety

and

their

related

symptoms

of

social

dysfunction

and

loss

of

confidence(10),

and

was

measured

using

the

GHQ-12

where

a

score

of

11

and

above

out

of

the

total

36

score,

is

considered

as

a

positive

case.(11)

Personal

data

were

collected

using

a

self-administered

questionnaire

that

included

the

socio-demographic

characteristics,

family

history

of

psychiatric

illness,

smoking

status,

their

willingness

to

receive

psychological

therapy

and

their

perception

about

their

glycemic

control.

Other

clinical

data

were

collected

using

a

data

extraction

sheet

from

the

patients

file

and

that

included

the

diabetes

characteristics,

presence

of

complication

and

presence

of

comorbidities.

The

participants

were

informed

about

the

nature

of

the

study,

its

purpose

and

assured

that

data

will

be

kept

anonymous

and

confidential.

Statistical

analysis:

Frequency

tables

were

used

to

describe

qualitative

data

and

mean

and

standard

deviations

were

used

to

describe

quantitative

data

while

Chi-square

test

was

used

to

compare

proportions

between

categorical

variables.

Logistic

regression

was

used

to

identify

the

most

significant

predictors

associated

with

psychological

morbidity

among

Arab

diabetic

patients.

Dichotomous

independent

variables

and

the

main

outcome

were

entered

into

the

binary

logistic

regression

model

of

the

Statistical

Package

for

the

Social

Sciences

(SPSS)

program

and

odds

ratio

(OR)

was

used

to

estimate

the

strength

of

the

relationship

between

psychological

morbidity

and

the

most

significant

predictors

associated

with

psychological

morbidity

among

Arab

diabetic

patients

using

the

backward

stepwise

(Wald)

method

in

the

logistic

regression

analysis.

A

total

of

459

Arab

diabetic

patients

were

approached

of

which

422

agreed

to

participate

giving

us

a

response

rate

of

91.9

%.

Seven

of

them

were

excluded

from

the

study

due

to

missing

data

in

their

questionnaire,

so

a

total

of

415

subjects

are

included

in

the

analysis

of

the

study.

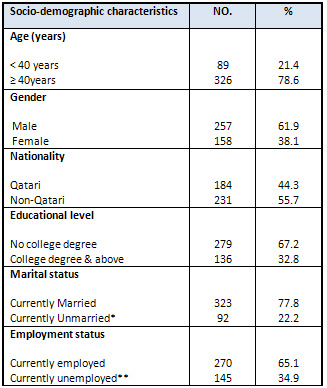

Their

socio-demographic

characteristics

are

summarised

in

Table

1,

and

their

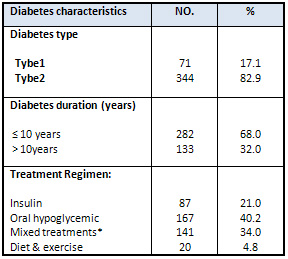

diabetes

characteristics

are

summarised

in

Table

2.

Table

1:

Distribution

of

socio-demographic

characteristics

of

the

study

subjects.(n=415)

*It

includes

the

single,

divorced

and

the

widowed.

**

It

includes

the

unemployed,

retired,

students

and

housewives.

Table

2:

Distribution

of

diabetes

characteristics

of

the

study

subjects.

(n=415)

*

This

includes

those

on

insulin

and

oral

hypoglycemics

The

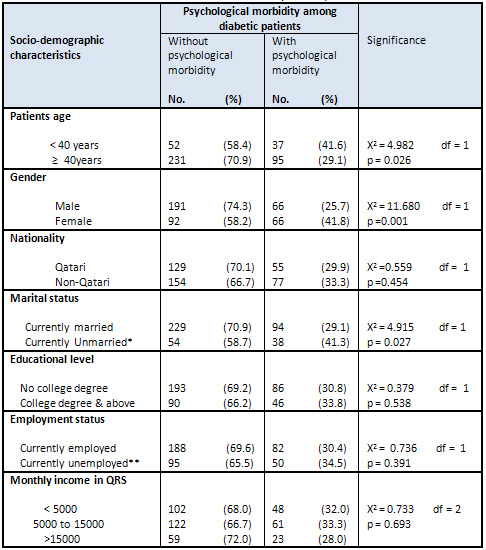

prevalence

of

psychological

morbidity

among

Arab

diabetic

patients

attending

primary

health

care

centres

in

Qatar

was

31.8%,

where

a

higher

percentage

of

those

in

the

early

adulthood

period

(<

40

years)

have

psychological

morbidity

than

those

in

the

middle

or

late

adulthood

period

(>

40years)

(41.6%

vs.

29.1%)

and

this

difference

is

statistically

significant

(p<0.05)

-

Table

3.

Concerning

gender

a

lower

proportion

of

males

suffer

from

psychological

morbidity

as

compared

to

females

(25.7%

vs.

41.8%)

and

this

difference

is

statistically

significant.

When

comparing

the

patients

in

terms

of

nationality,

the

percentage

of

patients

with

psychological

morbidity

is

slightly

higher

among

non-Qatari's

(33.3%)

than

Qatari's

(29.9%)

but

this

difference

did

not

reach

a

significant

value

(p>0.05).

Table

3:

Psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

their

socio-demographic

characteristics.

(n=415)

*

It

includes

the

single,

divorced

and

the

widowed.

*

It

includes

the

single,

divorced

and

the

widowed.

**

It

includes

the

unemployed,

retired,

students

and

the

housewives.

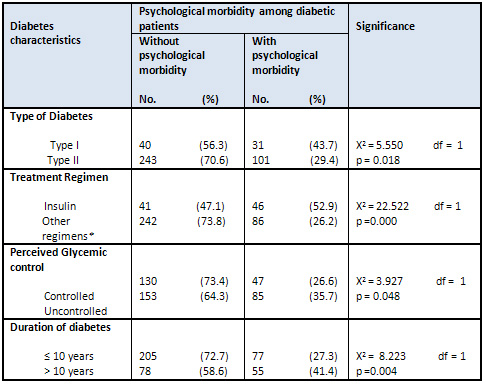

Concerning

the

patient's

diabetes

characteristics

there

is

a

significant

difference

between

them

in

terms

of

type

of

diabetes.

Higher

percentage

of

patients

with

type

I

have

psychological

morbidity

than

those

with

type

II

(43.7%

vs.29.4%),

as

shown

in

Table

4.

Conformingly

a

higher

proportion

of

patients

who

are

using

insulin

only

have

psychological

morbidity

than

those

who

are

using

other

regimens

(oral

hypoglycemic,

diet

&

exercise

or

mixed

treatments)

(52.9%

vs.

26.2%).

This

difference

is

statistically

significant.

The

percentage

of

patients

with

perceived

uncontrolled

diabetes

who

have

psychological

morbidity

are

higher

than

those

who

perceive

a

good

control

of

their

diabetes

(35.7%

vs.

26.6%).

This

difference

is

statistically

significant.

Furthermore

41.1%

of

patients

with

diabetes

duration

longer

than

10

years

suffer

from

psychological

morbidity

as

compared

to

27.3%

among

those

with

a

diabetes

duration

less

than

or

equal

to

10

years.

This

difference

is

statistically

significant.

Table

4:

Psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

their

diabetes

characteristics.(n=415)

*

This

includes

those

on

oral

hypoglycemic,

diet

&

exercise

or

mixed

treatments.

*

This

includes

those

on

oral

hypoglycemic,

diet

&

exercise

or

mixed

treatments.

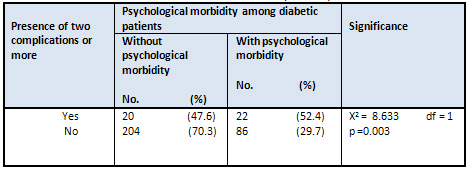

When

comparing

the

distribution

of

psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

the

existence

of

more

than

one

complication

in

the

same

individual,

higher

proportions

of

patients

with

two

or

more

complications

have

psychological

morbidity

than

those

with

no

documented

complications

(52.4%

vs.

29.7%),

Table

5.

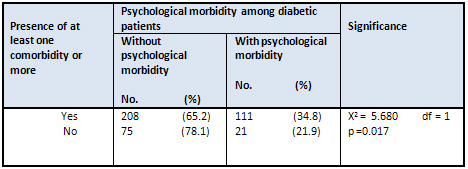

Moreover

those

who

have

at

least

one

or

more

comorbidities,

regardless

of

the

type

of

comorbidity,

have

a

higher

percentage

of

psychological

morbidity

than

those

with

no

existing

comorbid

disease

(34.8%

vs.

21.9%).

This

difference

is

statistically

significant,

as

demonstrated

in

Table

6.

Table

5:

Psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

the

presence

of

two

complications

or

more.

(n=332)

Table

6:

Psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

presence

of

at

least

one

comorbidity

or

more.

(n=415)

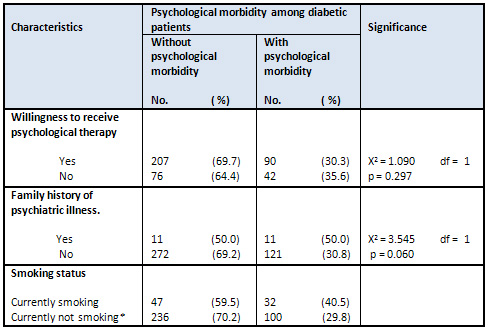

There

is

no

statistically

significant

difference

between

patients

with

psychological

morbidity

according

to

their

willingness

to

receive

psychological

therapy,

family

history

of

psychiatric

illness

and

smoking

status

(p>0.05),

as

illustrated

in

Table

7.

Table

7:

Psychological

morbidity

among

diabetic

patients

according

to

their

willingness

to

receive

psychological

therapy,

family

history

of

psychiatric

illness

and

smoking

status.

(n=415)

*This

includes

the

ex-smoker

and

those

who

never

smoked

| PREDICTORS

OF

PSYCHOLOGICAL

MORBIDITY

AMONG

ARAB

DIABETIC

PATIENTS |

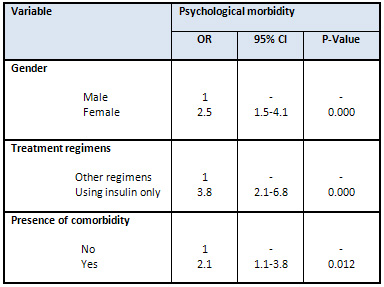

The

determinants

that

have

been

found

to

be

significantly

associated

with

psychological

morbidity

using

the

Pearson's

chi-square

test

are

re-analyzed

again

using

the

multivariate

binary

logistic

regression

to

adjust

for

the

confounding

effect

between

independent

variables

(determinants

of

psychological

morbidity)

and

the

dependent

variable

(psychological

morbidity).

Results

were

presented

in

Table

8.

Regarding

gender;

being

a

female

nearly

doubles

the

chance

of

having

psychological

morbidity

as

they

are

2.5

times

more

likely

to

have

psychological

morbidity

than

males

(OR=2.5,

95%

CI=1.5-4.1),

on

the

other

hand

patients

using

insulin

only

are

3.8

times

more

likely

to

have

psychological

morbidity

than

those

using

other

regimens

(OR=3.8,

95%

CI=2.1-6.8).

Similarly

those

patients

who

had

coexisting

morbidities

are

about

two

times

more

likely

to

have

psychological

morbidity

(OR=2.4,

95%

CI=1.1-3.8)

than

those

who

did

not.

Table

8:

The

most

significant

predictors

associated

with

psychological

morbidity

among

Arab

diabetic

patients

using

the

binary

logistic

regression

analysis

This

cross

sectional

study

explored

the

prevalence

of

psychological

morbidity

among

Arab

diabetic

patients

attending

primary

health

care

centres

in

Qatar

in

order

to

draw

the

attention

to

the

health

care

provided

to

patients

with

a

highly

prevalent

disease

in

the

country

which

is

diabetes

as

an

effort

to

improve

the

quality

of

care

provided

to

them

and

help

in

reducing

the

burden

of

this

prevalent

disease.

This

study

used

a

simple,

inexpensive,

screening

instrument,

which

has

been

used

in

different

studies

with

similar

primary

health

care

settings.

The

response

rate

in

this

study

was

91.9%

which

is

relatively

high

especially

when

we

are

addressing

psychological

morbidity

that

might

be

considered

as

a

stigma

in

the

Arab

world.

However,

the

entire

participants

were

given

a

full

explanation

of

the

nature

of

the

study

and

assurance

that

all

the

data

will

be

kept

anonymous.

Moreover

the

questionnaire

was

distributed

by

the

same

individuals

providing

the

service

i.e.

the

diabetic

educators,

making

it

more

acceptable

to

the

participants.

This

study

found

that

almost

one

third

of

the

Arab

diabetic

patients

in

Qatar

had

psychological

morbidity

(31.8%)

and

this

comes

in

agreement

with

many

international

studies

conducted

among

diabetic

patients

as

in

the

Australian

study,

which

found

that

the

prevalence

of

depression

was

30%

while

anxiety

was

35%(12)

and

similar

finding

were

reported

in

a

Greek(13)

study

and

in

a

Bangladesh

study(14).

On

the

other

hand

some

other

studies

reported

a

much

lower

prevalence

as

two

American

studies(3,

15)

reported

a

prevalence

of

10.1%

for

anxiety

and

8%

for

depression,

but

in

both

of

these

studies

a

telephone

survey

approach

was

used

and

this

might

explain

the

lower

prevalence

of

psychological

morbidities

reported

in

both

of

these

studies

as

it

might

have

excluded

people

who

do

not

have

land-line

phones

in

their

household,

the

homeless,

and

institutionalized

populations,

i.e.

the

low

social

class

people

who

might

have

a

higher

prevalence

of

psychological

morbidity.

Beside

that

people

having

psychological

morbidity

might

be

reluctant

to

answer

the

call

and

participate

in

such

a

survey.

Other

studies

found

a

much

higher

prevalence,

like

the

Iranian

study

which

reported

a

prevalence

of

depression

to

reach

as

high

as

71.8%,

but

this

study

was

conducted

in

a

hospital

setting

which

might

be

different

from

the

setting

used

in

the

present

study

in

terms

of

the

severity

of

diabetes

and

presence

of

more

severe

complications

and

or

other

comorbidities(5).

Although

studies

conducted

in

the

GCC

region

reported

a

more

or

less

similar

rates

as

the

present

study,

like

the

study

conducted

in

Bahrain(6)

and

the

UAE(7),

another

study

conducted

in

Bahrain

found

a

higher

prevalence(16)

than

the

present

study

and

this

again

might

be

explained

by

the

fact

that,

the

investigator

used

a

mixture

of

primary,

secondary

as

well

as

tertiary

level

care

as

a

setting

for

their

study,

as

this

population

might

include

cases

with

more

debilitating

complications.

In

general

the

variation

in

the

prevalence

of

PM

among

diabetic

patients

might

partly

be

explained

by

the

use

of

multiple

tools

to

assess

psychological

morbidities

such

as

the

GHQ,

PHQ,

BDI

and

the

HADS

as

well

as

whether

or

not

the

tool

used

has

been

validated

to

be

used

among

diabetic

patients

or

not.

Among

other

factors

that

might

contribute

to

this

variations

are

the

geographical

location

(urban

vs.

rural),

ethnicity

of

the

subjects

and

the

setting

of

the

study

(primary

care,

community

based,

or

hospital

based).

Gender

was

among

the

most

significant

predictors

of

PM

in

this

study

as

it

has

been

found

that

females

were

more

likely

to

have

PM

than

males

and

this

comes

in

agreement

with

many

studies(13)

and

the

fact

that

women

are

more

susceptible

to

PM

especially

depression

may

be

explained

by

the

theory

that

the

biological

and

physical

make

up

of

women

automatically

puts

them

more

at

risk

of

developing

psychological

morbidity(17)

as

from

puberty

onwards,

fluctuating

hormone

levels

affects

their

body

both

physically

and

emotionally.

Similarly,

during

and

after

pregnancy

women

may

be

particularly

vulnerable

to

depressive

disorders

such

as

postpartum

depression

and

postpartum

psychosis.

In

addition

to

biological

factors,

they

also

tend

to

be

more

affected

by

the

environment

around

them,

and

strive

for

perfection

both

physically

and

otherwise.

This

predefined

social

role,

both

increases

the

pressure,

which

they

place

on

themselves.

This

study

as

well

as

many

other

studies

reported

that

insulin

use

increases

the

likelihood

of

developing

psychological

morbidity(18,19);

this

might

be

explained

by

the

fact

that

these

patients

have

injection

related

anxiety

especially

when

the

insulin

is

self

injected,(20)

as

insulin

self-management

can

be

burdensome,

especially

when

patients

must

deal

with

their

diabetes

all

day

and

every

day,

by

self-monitoring

of

the

blood

glucose,

taking

insulin

and

making

sometimes

complex

decisions

about

insulin

dosage

in

relation

to

physical

activity

and

diet.

Other

factors,

such

as

worries

about

hypoglycemia,

gaining

weight,

the

impact

of

insulin

therapy

on

the

social

environment

and

feeling

of

failure

as

insulin

therapy

signifies

that

one

has

failed

to

manage

diabetes

with

diet/tablets(21).

Many

physicians

also

threaten

their

patients

with

insulin

as

a

final

solution

for

controlling

diabetes,

creating

a

great

feeling

of

anxiety

once

insulin

is

initiated.

Patients

also

want

to

avoid

injections

because

they

see

insulin

injections

as

a

social

stigma

that

labels

them

as

diabetic.

In

addition

those

who

are

using

insulin

only

to

control

their

diabetes,

as

in

the

present

study,

are

prone

to

more

daily

insulin

injection,

as

well

as

since

their

failure

is

intensified

as

they

think

that

no

other

treatment

could

possibly

be

effective

with

their

diabetes

and

their

one

and

only

chance

is

insulin

to

have

a

better

control.

It

is

well

known

that

most

diabetes

patients

have

a

number

of

comorbidities(22)

such

as

hypertension,

hyperlipidemia

and

the

present

study

showed

that

there

is

a

significant

relationship

between

the

presence

of

comorbidity

and

PM

by

both

univariate

and

multivariate

analysis.

This

finding

agrees

with

studies

that

explore

this

relationship

such

as

Ali

et

al.(23,24).

However,

when

comparing

each

comorbid

disease

separately

such

as

hypertension

and

hyperlipidemia,

the

study

analysis

failed

to

find

a

significant

difference,

and

this

might

be

attributed

to

the

fact

that

the

study

addressed

very

prevalent

comorbidities

in

Qatar

as

most

patients

have

them

whether

they

have

psychological

morbidity

or

not

and

maybe

the

study

did

not

have

enough

power

in

some

of

these

comorbidities

to

detect

a

significant

difference

such

as

in

asthma.

The

relationship

between

psychological

morbidity

and

age

must

be

interpreted

with

caution

as

some

studies

showed

that

psychological

morbidity

has

been

shown

to

be

common

among

younger

people

(25,26).

This

might

be

explained

by

many

factors

as

older

people

have

fewer

economic

hardships

and

fewer

experiences

of

negative

interpersonal

exchanges,

beside

younger

adults

may

be

more

reactive

to

life

stressors,

and

they

may

cope

less

effectively

with

these

conditions

than

older

adults(26).

On

the

other

hand

different

studies

showed

contradicting

results,(27)

with

depression

being

more

common

among

older

people

although

older

patients

are

less

likely

to

report

depressive

symptoms

and

they

might

have

suboptimal

cognitive

functions,

which

makes

it

difficult

to

diagnose

psychological

morbidity

among

them(28).

Diabetes

duration

has

been

addressed

in

many

studies

as

a

determinant

of

psychological

morbidity,

where

some

studies

found

that

those

with

longer

duration

of

diabetes

are

more

likely

to

have

PM

than

those

with

a

shorter

duration(13,29).

This

might

be

attributed

to

the

fact

that

living

longer

with

such

a

demanding

disease

exposes

the

individual

to

a

longer

duration

of

stress

that

might

exhaust

his

coping

resources.

Also

it

should

be

noted

that

studies

reported

that

after

ten

years,

the

likelihood

of

developing

diabetes

complications

increases

in

both

types

of

diabetes

as

reported

by

Ammari

(30)

and

Basit

et

al(31).

In

addition

this

study

did

not

show

a

significant

relationship

between

currently

smoking

and

psychological

morbidity

and

this

is

in

agreement

with

Nasser

et

al(6)

while

there

are

other

studies

that

found

a

significant

relationship

between

smoking

and

psychological

morbidity(32).

This

finding

should

be

interpreted

with

caution,

as

smoking

is

not

defined

in

the

same

way

in

many

of

the

studies

addressing

smoking.

Nevertheless,

it

should

be

worth

noting

that

the

majority

of

patients

reported

their

willingness

to

receive

psychological

therapy

when

needed

(71.6%).

This

should

encourage

the

decision

makers

in

the

country

to

consider

incorporating

preventive

psychological

interventions

into

primary

care

services

directed

towards

diabetic

patients

to

enhance

adaptation

to

diabetes

and

reduce

related

stress.

Strengths

and

limitations:

As

in

any

mental

health

screening

using

a

questionnaire,

one

cannot

rule

out

the

social

desirability

bias

or

mental

health

bias;

also

the

clinical

characteristics

in

the

study

are

based

on

the

existing

data

in

the

patient's

file,

as

the

PHC

department

are

still

in

the

process

of

developing

guidelines

which

will

help

in

standardizing

the

services

provided

in

all

PHC

centers

in

Qatar.

However,

this

study

has

its

strength,

as

although

it

is

targeting

a

sensitive

issue

in

the

Arab

world

it

manages

to

achieve

a

high

response

rate

(91.9%),

and

the

investigator

used

a

simple

inexpensive

validated

tool,

which

can

be

used

for

future

screening

of

diabetic

patients

for

psychological

morbidity.

In

addition

this

study

can

act

as

a

baseline

for

the

planning

of

preventive

mental

health

services

for

diabetics

in

Qatar.

Almost

one

third

of

Arab

diabetic

patients

attending

primary

health

care

centres

in

Qatar

have

psychological

morbidity

where

female

gender,

insulin

use

and

presence

of

multiple

comorbidities

are

the

most

significant

predictors

of

psychological

morbidity

among

them.

More

studies

need

to

be

done

in

this

field

in

order

to

identify

the

risk

factors

for

psychological

morbidity

among

people

with

chronic

disease

especially

diabetes,

and

to

improve

the

mental

health

services

that

are

offered

to

these

people

as

in

this

study

about

two

thirds

of

Arab

diabetic

patients

showed

their

interest

in

receiving

psychological

therapy

if

they

need

it.

1.

WHO.

The

Constitution

of

the

World

Health

Organization.

Official

Records

of

the

World

Health

Organization,

No.

2,

P.

100.

New

York

1948.

2.

Moussavi

S,

Chatterji

S,

Verdes

E,

Tandon

A,

Patel

V,

Ustun

B.

Depression,

chronic

diseases,

and

decrements

in

health:

results

from

the

World

Health

Surveys.

Lancet

2007;370:852-8.

3.

C.

Li,

E.S.

Ford,

T.W.

Strine,

A.H.

Mokdad,

Prevalence

of

depression

among

U.S.

adults

with

diabetes:

findings

from

the

2006

behavioral

risk

factor

surveillance

system,

Diabetes

Care

2008;31(1):105-107.

4.

Pouwer

F,

Beekman

AT,

Nijpels

G,

Dekker

JM,

Snoek

FJ,

Kostense

PJ

et

al.

Rates

and

risks

for

co-morbid

depression

in

patients

with

type

2

diabetes

mellitus:

results

from

a

community-based

study.

Diabetologia

2003;

46:

892-898.

5.

Khamseh

ME,

Baradaran

HR,

Rajabali

H.

Depression

and

diabetes

in

Iranian

patients:

a

comparative

study,

Int.

J.

Psychiatry

Med.2007;

37(1):81-86.

6.

Nasser

J,

Habib

F,

Hasan

M,

Khalil

N.

Prevalence

of

Depression

among

People

with

Diabetes

Attending

Diabetes

Clinics

at

Primary

Health

Settings.

Bahrain

Medical

Bulletin

2009;31(3):1-12.

7.

El-rufaie

OE,

Bener

A,

Ali

TA,

Abuzeid

MS.

Psychiatric

morbidity

among

type

II

diabetic

patients:

a

controlled

primary

care

survey.

Primary

Care

Psych

1997;3:189-194.

8.

Goldney

RD,

Phillips

PJ,

Fisher

LJ,

Wilson

DH.

Diabetes,

depression,

and

quality

of

life:

a

population

study.

Diabetes

Care

2004

;27(5):1066-70.

9.

McVeigh

K

H,

Mostashari

F,

Thorpe

L

E.

Serious

Psychological

Distress

Among

Persons

With

Diabetes-New

York

City,

2003.JAMA

2005;

293(4):419-420.

10.

Gao

F,

Luo

N,

Thumboo

J,

Fones

C,

Li

S

and

Cheung

Y.

Does

the

12-item

General

Health

Questionnaire

contain

multiple

factors

and

do

we

need

them?.

Health

and

Quality

of

Life

Outcomes

2004;2:63.

11.

El-Rufaie

O

E,

Bener

A,

Abuzied

M

S,

Ali

T

A.

Psychiatric

screening

among

Type

II

diabetic

patients

:Validity

of

the

General

Health

Questionnaire-12.

Saudi

medical

journal.1999;20(3):

246-250.

12.

Graco

M,

Berlowitz

DJ,

Fourlanos

S,

Sundram

S.

Depression

is

greater

in

non-English

speaking

hospital

outpatients

with

type

2

diabetes.

Diabetes

Res

Clin

Pract.

2009;83(2):e51-3.

13.

Sotiropoulos

A,

Papazafiropoulou

A,

Apostolou

O,

Kokolaki

A,

Gikas

A,

Pappas

S.

Prevalence

of

depressive

symptoms

among

non

insulin

treated

Greek

type

2

diabetic

subjects,

BMC

Res.

Notes

2008;1:101.

14.

Asghar

S,

Hussain

A,

Ali

SM,

Khan

AK,

Magnusson

A.

Prevalence

of

depression

and

diabetes:

a

population-based

study

from

rural

Bangladesh.

Diabet.

Med.

2007;24(8):872-

877.

15.

Fisher

L,

Skaff

M

M,

Mullan

T

J,

Arean

P.

A

longitudinal

study

of

affective

and

anxiety

disorders,

depressive

affect

and

diabetes

distress

in

adults

with

Type

2

diabetes.

Diabet

Med.2008;25(9):1096-1101.

16.

Almawi

W,

Tamim

H,

Al-Sayed

N,

Arekat

MR,

Al-Khateeb

GM,

et

al.

Association

of

comorbid

depression,

anxiety,

and

stress

disorders

with

Type

2

diabetes

in

Bahrain,

a

country

with

a

very

high

prevalence

of

Type

2

diabetes.

J

Endocrinol

Invest.

2008;31(11):1020-4.

17.

Kornstein

SG.

Gender

differences

in

depression:

implications

for

treatment.

J

Clin

Psychiatry

1997;

58(suppl

15):12-8.

18.

Pouwer

F,

Hermanns

N.

Insulin

therapy

and

quality

of

life.

A

review.

Diabetes

Metab

Res

Rev

2009;25

Suppl

1:S4-S10.

19.

Noh

JH,

Park

JK,

Lee

HJ,

Kwon

SK,

Lee

SH,

et

al.

Depressive

symptoms

of

type

2

diabetics

treated

with

insulin

compared

to

diabetics

taking

oral

anti-diabetic

drugs:

a

Korean

study.

Diabetes

Res

Clin

Pract

2005;69(3):243-8.

20.

Fu

AZ,

Qiu

Y,

Radican

L.

Impact

of

fear

of

insulin

or

fear

of

injection

on

treatment

outcomes

of

patients

with

diabetes.

Curr

Med

Res

Opin.

2009

;25(6):1413-20.

21.

Ahmed

U

S,

Junaidi

B,

Ali

A

W,

Akhter

O,

Salahuddin

M,

et

al.

Barriers

in

initiating

insulin

therapy

in

a

South

Asian

Muslim

community.

Diabetic

Medicine

2010;27(2):169-174.

22.

Maddigan

SL,

Feeny

DH,

Johnson

JA.

Health-related

quality

of

life

deficits

associated

with

diabetes

and

comorbidities

in

a

Canadian

National

Population

Health

Survey.

Qual

Life

Res.

2005;

14:

1311-1320.

23.

Commonwealth

of

Australia.

The

Mental

Health

of

Australians

2

Report

on

the

2007

National

Survey

of

Mental

Health

and

Wellbeing.

Commonwealth

of

Australia

.Sydney

.2009.

24.

Ali

S,

Davies

M

J,

Taub

N

A,

Stone

M

A,

Khunt

K.

Prevalence

of

diagnosed

depression

in

South

Asian

and

white

European

people

with

type

1

and

type

2

diabetes

mellitus

in

a

UK

secondary

care

population.

Postgrad

Med

J.2009;85:238-243.

25.

McCollum

M,

Ellis

SL,

Regensteiner

JG,

Zhang

W,

Sullivan

PW.

Minor

depression

and

health

status

among

US

adults

with

diabetes

mellitus.

Am

J

Manag

Care

2007;13(2):65-72.

26.

Schieman

S,

Van

Gundy

K,

Taylor

J.

The

relationship

between

age

and

depressive

symptoms:

a

test

of

competing

explanatory

suppression

influences.

J

Aging

and

Health

2002;14:260-

27.

Stekml

ML,

Vinkers

DJ,

Roos

JR,

Van

der

Mast

ATF,

Beekman

RGJ:

Natural

History

of

Depression

in

oldest

old.

Population-

Based

prospective

Study.

Brit

J

Psychiatry

2006;188:65-69.

28.

Amati

A

.

A

clinical

review

of

depression

in

elderly

people.

BMC

Geriatrics

2010,

10(Suppl

1):L28.

29.

Aikens

JE,

Perkins

DW,

Piette

JD,

Lipton

B.

Association

between

depression

and

concurrent

Type

2

diabetes

outcomes

varies

by

diabetes

regimen.

Diabet

Med

2008;25(11):1324-9.

30.

Ammari

F.

Long-term

complications

of

type

1

diabetes

mellitus

in

the

western

area

of

Saudi

Arabia.

Diabatologia

croatica

2004;33(2):59-63.

31.

Basit

A,

Hydrie

M

Z

I,

Hakeem

R,

Ahmedani

M

Y,

Masood

Q.

Frequency

of

chronic

complications

of

type

2

diabetes.

Journal

of

College

of

Physicians

and

Surgeons

Pakistan

2004;

14

(2):79-83.

32.

Haire-Joshu

D,

Heady

S,

Thomas

L,

Schechtman

K,

Fisher

EB

Jr.

Depressive

symptomatology

and

smoking

among

persons

with

diabetes.

Res

Nurs

Health

1994;17(4):273-82.