|

PowerPoint presentations

in Medical Conferences in Iraq. (A Qualitative

Study)

Ali A. Kadhim

Abutiheen

Correspondence:

Dr. Ali

A. Kadhim Abutiheen, M.B, Ch.B. - F.I.B.M.S.

(Consultant Family Physician)

Assistant Professor - Chairman

Family & Community Medicine Department

Kerbala University

College of Medicine

Iraq

Email: aliabutiheen@yahoo.com,

aliabutiheen@uokerbala.edu.iq

|

Abstract

Background:

PowerPoint (PPT) presentations are

the predominant kind of presentations

used in medical lectures, seminars and

conferences in recent years. Many physicians

and scientists are unaware of the rules

and guidelines in preparing and conducting

PPT presentations including many aspects

of it.

Objectives: To evaluate the state

of PowerPoint presentations and related

matters in Medical Conferences in Iraq.

Methods: This was a mixed qualitative

study, using observational approach. A

checklist prepared by the investigator,

was used to predict certain aspects in

presentations, presenters approach as

well as conference organization. Eight

conferences were included from 4 governorates

in Iraq for the period from November 2009

to December 2011. A total of 102 PowerPoint

presentations were included in the study.

Oral approval from the head of the conference

or organizing committee of the conferences

was taken prior to doing these observations.

Results: One out of the 8 conferences

starts on time with an average 30 minutes

delay. Thirty one (30%) of presenters

are facing problems, 43 (42%) use very

small size in some of their slides, 36

(35%) had mismatched colours. Fifty (49%)

used more than 15 lines per slides and

12 (12%) used more than 20 lines per slide.

Too many slides per presentation were

noticed with 28 and 37 using extra slides

and 19 using over animation in some slides.

Laser pointers were used by 39 of the

presenters, 13 (33%) of those used it

in a non-proper way, while 15 had delays

for 5 minutes and more. Side talks, mobile

rings and mobile talk were present in

more than 40% of presentations.

Conclusions and Recommendations:

Many problems were noticed with presentations

in medical conferences. Organizers need

to give more efforts toward logistics,

delays in time, presentation duration,

and assure a quiet environment. Presenters

should give consideration to their facing,

voice, pointer use as well as preparing

their PPT slides properly.

Key words: PowerPoint, PowerPoint

Presentation, Conference, Effective presentation,

Information and Communication Technology,

Iraq

|

Educational technology and audiovisual aids

had become an integral part of teaching, training

and giving lectures or presentations all over

the world (1-3). Technology and the term Information

and Communication Technology (ICT) are widely

used, and have become an essential element of

teaching environment in universities and institutes

(4-7).

PowerPoint (PPT) presentations are the predominant

kind of presentations used in medical lectures,

seminars and conferences in recent years as

well as in other sciences. Teachers and scientists

should know how to use ICT; even the general

population should know the proper use of it

in this era (1, 8-10). PPT can help in organizing

thoughts, time management and getting attention

and attraction of the audience. In addition,

most audiences like PPT presentations as they

can follow and remember the presentation (4,

7, 9, 11-13).

As any other technique or tool, PPT has some

weak points or disadvantages. Edward Tufte and

others have criticized PPT as being an evil

and the worst invention, for being teacher centered,

decreased thinking of the audience and other

issues (14-18). Though these limitations could

be related to the person constructing the PPT

slides or the presenter themmself not the program

(6, 17, 19-21). This argument might be usual

event with any invention.

Unfortunately, many presenters use PPT improperly;

thus it becomes distracting, dissociative and

decreases the effectiveness of the presentation,

instead of being additive and focused on the

presentation content. This could be related

to the fact that many physicians, teachers and

researchers are unaware of the rules and guidelines

of preparing and conducting PPT presentations

and slides, while others have little experience

with computers and programs or are not trained

on how to make an effective presentation (7,

22, 23).

Frequently presenters rely on the PPT, reading

slides from the laptops or screen, moving slides,

and thus losing communication and eye to eye

contact with the audience. Missing a basic rule

of facing in the audience's direction, not the

slides; he\she should be the focus of attention,

not the screen. PPT should add to his\her talk,

and deal with it as a supplement or an aid (20,

24-29).

An effective presentation should be interactive.

Success and productivity of a presentation depends

on presenters' ability, experience of how to

communicate with the audience, gain their attention

and use body languages efficiently, rather than

type and quality of the visual aids used (22,

26, 30).

Presenters' voices should be clear and audible

to all attendants while a soft monotonous voice

will negatively affect the presentation. Presenters

should speak at a suitable pace, not being fast

and should finish on time. To achieve that,

rehearsing and practicing will help, as well

as other issues related to presentation and

its effectiveness (8, 22, 26, 27, 30-33). Another

helpful rule in time management is "the

lesser number of slides in a presentation the

better" and do not use over two slides

per minute (34, 35). So for a 15 minutes presentation

your slides should not to exceed 30 while 20-25

slides, or even less, will be most suitable.

Designing of PPT slides is a major factor related

to the effectiveness of the presentation, and

the basic rules in preparing slides are:

- Keep simple design first and use a clear font.

- Use same design, fonts and colours for all

slides.

- Keep slides margins clear.

- Use small letters, it is easier to read and

writing in capital letters should be restricted

to titles or keywords.

- The lesser the words in a slide the better.

- Bigger size of font is better; size for titles

should be bigger than text.

- Suitable size for text is 30-36, and do not

use text size less than 24, even in small halls,

and many writers recommend larger size. (11,

19, 20, 25, 33, 35-41).

A common pitfall in preparing slides is putting

too many words in a slide. To overcome this

issue the rule of six or (6*6) should be followed.

This means that each slide should not contain

over six lines and each line should not contain

over six words. Some researchers refer to the

rule of seven, others recommend five lines,

but the majority agree that it should not exceed

eight lines per slide. Others advise a maximum

of twenty words per slide (8, 12, 20, 31, 35-37,

42).

Colour use in designing slides is liked by presenter

and audience, but too many colours are distracting.

Not more than 4 colours per slide is advised.

Select text colours to match with background

colour, and contrast with it. So use dark colours

on light background and light colours on dark

backgrounds. Avoid combination of colours as

it is difficult to read (35-37, 40).

I prefer a light background (light not shiny)

and dark text as it less affected by lighting

of the halls. Lighting of the hall is often

needed and asked for by media and photographers

covering conferences. Also keeping a little

lighting is better for communication as the

presenter can see the audience and it is advisable

to decrease sleepiness and eye fatigue (41).

Sleeping in conferences or lectures is not uncommon.

Special effects in PPT design such as animation

and sound effects could add to presentation

a touch of life or action. But overuse of them

are distracting and annoying (4, 8, 9, 17, 33,

35, 36, 38, 40, 43, 44). The same is true with

a laser pointer, which is frequently used by

many presenters, if its use is non proper or

unnecessary (22, 26).

Images are easier to understand and stay in

the mind of audience, but too many or nonrelated

images may distract the audience. However, avoid

using images as a background. Also graphs and

charts will be much easier to read than tables.

Tables are more suitable for publication than

presentation. Try to replace tables by graphs

whenever possible in PPT, but graphs should

be easy for visualization and understood. Use

of videos or any multimedia in presentation

can add and stay in the mind longer, as long

as it is it's related to the topic, and time

allocated is enough. (17, 19, 21, 25, 33, 40,

42, 45, 46).

After all remember that audiences are sitting

in the hall to watch and listen to your talk,

research notes, updates, thoughts and your experience

in the medical or other field, not to your experience

in PPT program techniques, animation, and use

of colours, or to see unrelated pictures or

shapes. And as you use technology and PPT you

should know how to deal with it, or at least

the ABC of that. Always be ready for alternative

ways to give the presentation if technology

fails you, or electricity goes off.

However, if circumstances forced you to give

a presentation, or for any reason you want the

audience not to understand your talk or open

discussion, you can use the opposite of above

mentioned PPT rules.

Many pitfalls and problems have been noted with

preparing PPT slides, audiovisuals use, giving

presentations, and in organization of the conferences

in Iraq. Issues that presenters or organization

committees miss or underestimate, may have negative

effects on attendants, outcomes of presentations

and the conference. So the objective of this

study was to evaluate the state of PPT presentations

and some related issues in medical conferences'

organization in Iraq.

This was a mixed qualitative research study,

using observational approach. The study included

8 medical conferences or symposia held in 4

different provinces in Iraq for the period from

November 2009 to December 2011; the organizers

of the conferences were different parties: Ministry

of Health, Ministry of Higher Education and

Scientific Research, Medical Societies and some

were cooperations between them. Selection of

the presentation was random, depending on sequences

of the presentation in the conference and the

availability of the investigator.

A special checklist was prepared by the investigator,

in order to predict certain aspects in PPT presentation,

the presenters' approach as well as conference

organizations while attending conferences, such

as: starting time of conference with schedule,

starting of sessions, time allocated for presentation,

the introduction of the presenters by chairs

of session (whether adequate or non-adequate

or not observed).

Issues related to the presenter included the

following: facing (good, accepted, non- accepted);

voice (good, accepted, non-accepted); font type

(clear, accepted, non-clear); Font size ( large

= read easily, small = difficult to read, very

small = very difficult or could not be read);

colours used (good = matched, accepted, non-

accepted = mismatched); too many colours (more

than 5/slides); number of lines per slide (?10,

11-15, 16-19, ? 20); use of pictures; tables

and graphs (not used, good, accepted, non-accepted=

very difficult or could not be recognized, not

observed); use of laser pointer in presentation,

any method of usage of it (good, accepted, misuse

or overuse "when its use is distracting

or over-moved in annoying way".

Also number of slides per presentation (good,

accepted, too many); extra-slides presence "slides

that were not presented or discussed and just

passed on by presenters"; Animation (good

or accepted, overuse, not observed); the pace

or speed of presenter (good, accepted, fast);

commitment with time (finish on time or before,

delay 2-3 minutes, delay for 5 minutes or more);

time notification (notified on time or not);

response to notification (did not respond, responded

positively, not good response).

Other issues checked include: presence of side

talks, mobile ringing, mobile talk, quality

and arrangement of audiovisuals, disruption

or interruption of the presentations, and discussion

time as well any specific related issues.

To conduct these observations an oral approval

from the head of conference or head of organizing

committee of the conferences was taken prior

to doing these observations. Also names of conferences

were kept hidden only for the researcher, and

even names of presenters and their background

not recorded. Observations were translated to

frequencies and percentages and data expressed

as tables or figures.

A

total

of

102

PPT

presentations

were

included

in

the

study

from

8

conferences

conducted

in

four

different

Iraqi

governorates.

Only

one

conference

(12.5%)

started

on

time

of

schedule

with

average

30

minutes

delay

and

one

started

after

2

hours,

while

nearly

one

third

of

presentations

had

some

problems

in

audiovisuals

or

lighting

of

the

conference

hall.

Ninety

seven

(95.1%)

presenters

were

introduced

in

a

good

to

accepted

way

by

the

chairs

of

sessions.

And

94

(92.2%)

of

them

greeted

or

thanked

the

chair

or

audience

before

starting

their

presentation.

However

6

(5.9%)

had

a

weak

or

monotonous

voice

as

shown

in

Table

1.

Also

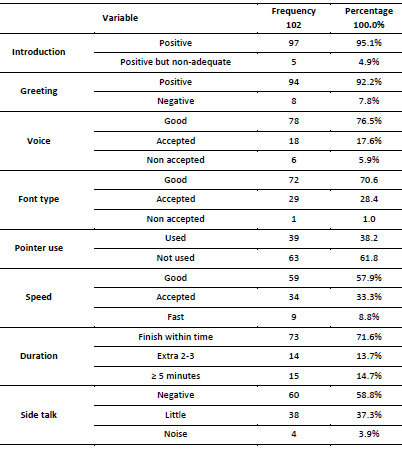

facing

and

eye

contact

problems

with

attendants

were

noticed

with

31

(30.4%)

of

the

presenters

(Figure

1).

There

was

little

problem

with

type

of

font

used,

most

of

them

were

clear

and

readable,

and

only

1

(1%)

used

non-accepted

font.

While

92

(90.2%)

used

small

size

font

and

43

(42.2%)

used

very

small

size

in

some

of

the

slides

they

used.

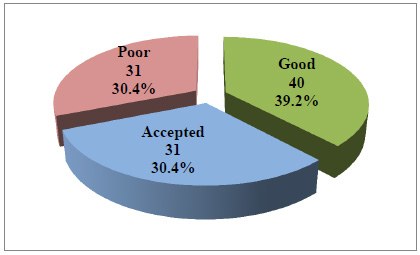

Fifty

(49.2%)

used

more

than

15

lines

per

slide,

while

12

(11.8%)

used

more

than

20

lines

per

slide

in

some

of

their

slides

(Figure

2).

Too

many

slides

per

presentation

were

noted

with

28

(27.5%),

and

37

(36.3%)

used

extra

slides.

Regarding

colours,

36

(35.3%)

had

mismatched

colours

in

their

slides

while

10

(9.8%)

used

too

many

colours

in

some

slides,

and

30

(30%)

used

some

graphs

or

tables

that

were

difficult

to

be

seen

or

understood

(Figure

3)

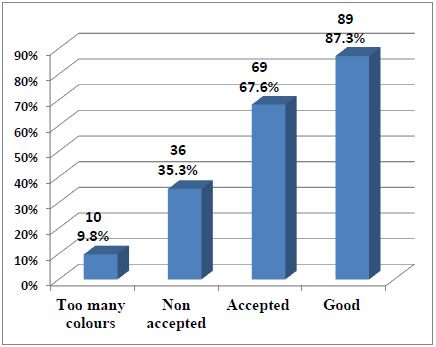

Over

animation

was

noted

with

19

(18.6%)

of

presenters

while

laser

pointers

were

used

by

39

(38.2%)

of

presenters;

of

those

13

(33.3%)

used

it

in

a

non-proper

way

or

unnecessarily

(Figure

4).

Nine

(8.8%)

of

presenters

were

fast

in

their

presentations

and

73

(71.6%)

finished

on

time

while

15

(14.7%)

delayed

for

5

minutes

and

more.

Forty

(39.2%)

presenters

were

notified

on

time,

and

7

(6.9%)

notified

for

more

than

one

time

after

time

was

exceeded.

However

the

response

for

notification

was

weak

in

13

(32.5%)

while

4

(10%)

ignored

time

notification.

Side

talks,

mobile

rings

and

mobile

talk

was

present

during

42

(41.2%)

presentations,

and

about

12

(11.8%)

presentations

were

interrupted,

and

in

most

cases

by

power

off

or

audiovisual

problems.

Table

1:

Frequency

and

Percentage

of

certain

attitudes

observed

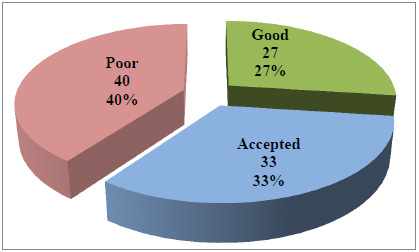

Figure

1:

Condition

of

Presenters

facing

the

audience

Figure

2:

Number

of

lines/slide

showed

by

presenters

in

some

of

their

slides

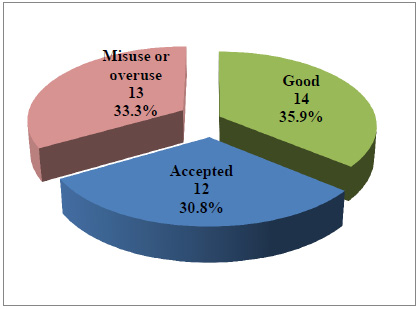

Figure

3:

Distribution

of

colours

used

in

slides

Figure

4:

Status

of

tables

and

graphs

presented.*(2

presentations

didn't

include

tables)

Figure

5:

Laser

pointer

usage

status.

PowerPoint

presentations

use

in

teaching,

learning

and

scientific

conferences

are

increasing

day

after

day.

Microsoft

in

2001

estimated

there

were

over

30

million

PPT

presentation

per

day,

so

imagine

the

number

nowadays(1,

28,

29).

Consider

Ian

Parker's

words

"appearing

in

meeting

nowadays

without

a

PPT

is

just

like

wearing

no

shoes"

(47).

So

researchers,

teachers,

scientists

should

have

competent

skills

on

how

to

prepare

a

PPT,

using

technology

fairly

and

giving

an

effective

presentation.

Each

of

these

areas

may

lead

to

bad

or

non-effective

presentations.

Also

they

can

be

boring

and

have

a

negative

impact

on

learning,

content,

attendance

and

retention

of

knowledge

(14,

17,

21,

28,

42,

48-50).

Delay

of

conferences

opening

was

quite

common

for

different

reasons.

But

a

common

reason

was

waiting

for

attendance

of

main

guests

such

as

ministers,

university

chancellor,

etc.,

who

usually

had

an

opening

speech.

Also

the

delay

was

present

in

most

lectures

sessions

openings.

However,

non-respect

to

time

could

be

a

social

problem

in

Iraq.

As

most

meetings

and

conferences

were

delayed

in

Iraq

up

to

the

highest

political

or

governmental

meetings

or

even

writing

the

Iraqi

Constitution.

Poor

preparedness

of

the

main

hall,

audiovisuals

and

computers

were

noted,

and

these

issues

had

negative

effects

on

presenters

and

materials.

Also

many

times

the

PPT

was

on

flash

ram

or

CD

and

not

on

main

computer,

and

had

not

been

tested.

Some

organizers

set

low

sited

datashows

that

were

affected

by

passing

of

guests

or

organizing

staff

in

front

of

the

screen.

Poor

facing

to

audience

was

present

in

nearly

one

third

of

presenters.

This

may

reflect

that

many

presenters

were

not

aware

or

had

not

considered

this

issue.

Though

sometimes

it

was

the

conference

organizers'

fault

who

did

not

put

a

laptop

or

screen

in

front

of

presenter.

This

mandated

the

presenter

to

read

from

the

screen

and

put

his/her

back

to

the

audience.

Some

presenters

were

smart

enough

to

try

to

overcome

this

situation

every

now

and

then

by

talking

to

audience,

while

others

kept

talking

without

any

consideration.

Another

problem

noticed,

was

that

the

slides

movement

was

not

done

by

the

presenters.

So

that

handicapped

the

presenter

and

required

them

to

tell

a

person

in

charge

to

move

slides

(next,

next..).

This

was

more

problematic

if

the

slides

were

not

organized,

if

they

wanted

to

go

back

to

a

certain

slide

and

if

there

were

extra

slides.

On

the

other

hand

some

presenters

had

very

little

experience

with

computers

or

PPT

programs

and

were

be

keen

for

someone

to

move

their

slides.

In

one

conference

there

was

a

laptop

in

front

of

presenters

but

the

show

was

from

another

computer

that

was

connected

to

a

datashow.

Though

they

offered

some

help,

it

was

confusing

for

presenter

as

well

as

audience.

As

in

most

conferences,

the

presenter

should

stand

in

an

almost

fixed,

static

area

that

gives

no

or

very

little

space

for

movement.

So

organizers

should

arrange

a

laptop

or

screen

in

front

of

them,

and

he\she

should

be

responsible

for

slides

transition,

and

presenters

should

know

how

to

do

it.

However,

an

important

issue

is

that

presenters

should

be

aware

and

care

about

facing

the

audience

as

well

as

using

effective

body

language.

The

use

of

remote

devices

in

presenters'

hands

would

be

very

helpful

supposing

that

presenters

are

familiar

with

the

use

of

them.

This

can

give

more

freedom

to

move

and

use

body

language.

Minor

problems

appeared

with

introduction

of

presenters

to

audience,

but

occasionally

it

wasn't

fair

enough.

Also

the

thanks

and

greetings

from

presenters

to

audience

and

chairmen

was

good.

Voice

problems

were

not

that

common

and

many

times

related

to

audio

devices

and

microphones.

But

more

voice

problems

were

noticed

in

discussion

sessions,

where

portable

microphones

were

poorly

functioning.

A

majority

use

small

size

font,

and

42%

used

very

small

size

font

that

was

difficult

to

be

read.

However

this

issue

is

directly

related

to

number

of

lines

used

per

slide,

as

49%

and

12%

had

used

slides

with

15-19

and

more

than

20

lines/

slide

respectively.

This

reflects

a

major

problem

that

is

very

awful

to

read,

if

one

can

read

it

in

the

first

place.

This

was

greatly

associated

with

tables

presented,

as

only

14%

of

tables

were

good.

So

presenters

should

reconsider

the

use

of

tables

in

their

presentation

or

use

suitable

graphs

instead

if

applicable.

Misuse

of

laser

pointer

was

noticed

with

one

third

of

its

users.

However

if

the

slides

were

prepared

according

to

PPT

slides

preparation

rules,

there

would

be

less

or

even

no

need

for

the

use

of

laser

pointer.

Instead

one

can

use

the

cursors

present

on

computer

keyboards

and

as

Jannette

Collins

explain

in

her

useful

article(26).

Big

numbers

of

slides

were

noticed

in

28%

of

presentations,

and

38%

included

some

extra

slides

or

unnecessary

slides,

that

not

been

shown

or

discussed.

Some

included

tens

of

these

slides.

This

reflects

poor

preparation,

poor

time

management,

no

consideration

for

time

allocation

for

each

slide

and

even

no

review

of

PPT,

or

rehearsal.

Good

colour

match

was

the

predominant

feature,

however

non-accepted

or

poorly

matched

colours

appeared

in

nearly

one

third

of

presentations.

On

other

hand

10%

of

presenters

used

too

many

colours

in

one

slide

or

more.

This

could

be

related

to

unawareness

of

colours

matching

issue,

or

they

thought

that

shining

and

frequent

colours

added

to

PPT,

while

the

reverse

could

happen.

Similar

explanations

could

account

for

use

of

over

animation

that

was

present

in

nearly

one

fifth

of

presentations.

We

believe

that

10

minute

presentations,

that

were

the

most

prevalent

duration

given,

is

not

a

fair

time

to

give

for

a

research

presentation

or

an

update.

Duration

of

15-20

minutes

is

more

suitable,

or

should

be

the

minimum

time

to

be

given.

Moreover,

when

being

beyond

time

for

any

reason,

the

chairperson

tends

to,

or

been

asked

to

reduce

time

allocated

on

the

schedule

for

even

less

than

10

minutes.

Short

duration

increased

the

act

of

giving

fast

presentation

that

is

a

non

preferred

event,

even

if

it

appeared

only

in

9%

of

presentations.

Going

fast

was

also

affected

by

bulk

of

data

presented,

big

number

of

slides,

and

running

out

of

time.

Short

duration

given

could

give

a

hint

as

to

why

some

presenters

exceeded

time

given

for

them.

But

definitely

it

was

not

the

only

excuse

as

15%

exceeded

5

minute

delays,

while

others

took

more

than

double

the

time

and

ignored

the

recurrent

notifications

on

time.

Side

talks

and

mobile

rings

lead

to

distraction

and

non-calm

or

noisy

environment

and

it

was

present

in

more

than

40%

of

presentations.

Mobile

rings

were

heard

not

only

from

audience,

but

sometimes

from

the

presenters

themselves

and

even

from

the

chair

committee

who

sometimes

had

side

talks.

Furthermore

some

chairpersons,

were

not

monitoring

time,

leaving

presenters

to

exceed

time

allocated

for

them;

that

is

a

major

responsibility

for

a

chair

person.

Interruption

of

presentation

was

another

unpleasant

event

and

unfortunately

it

was

present

in

nearly

10%

of

presentations

though

electricity

going

off,

which

is

a

common

event

in

Iraq

was

the

main

cause.

Sometimes

the

cause

was

related

to

audio-visuals

malfunction

and

weak

preparedness

of

the

organizing

committee.

The

fact

that

only

one

person

evaluated

the

presentations,

is

one

of

the

limitation

of

this

study.

But

it

could

be

a

strength

also,

as

multiple

observers

would

have

different

standards

and

ranking.

After

all

the

study

aims

to

highlight

the

issue,

to

try

to

raise

standards

of

PPT

presentation

design,

conference

organization,

and

effective

lecturing.

Another

limitation

was

the

general

difficulty

of

recording

observations

while

attending

an

event,

as

we

are

humans

and

we

cannot

record

all

observations.

Presenters

in

these

conferences

were

from

all

over

Iraq,

and

many

of

them

were

not

physicians.

So

what

appeared

in

these

medical

conferences

can

be

applied

to

scientific

conferences

in

other

fields,

and

actually

same

issues

noticed

in

them

out

of

this

study.

In

conclusion,

there

are

many

pitfalls

with

presentations

in

medical

conferences

in

Iraq.

Medical

colleges,

conferences'

organizers

and

medical

personnel

need

to

give

more

efforts

for

PPT

slides

preparation

based

on

specific

rules.

Also

they

need

to

consider

time

delay,

duration

given

for

presenters,

logistics,

conference

hall

preparation,

selection

and

role

of

chair

persons

and

to

assure

a

quiet

environment.

Presenters

should

give

consideration

to

their

facing,

voice,

pointer

use

as

well

as

their

slide

preparation

as

well

as

skills

in

giving

an

effective

presentation.

Further

studies

on

this

area

and

issues

are

recommended.

1.

Savoy

A,

Proctor

RW,

Salvendy

G.

Information

retention

from

PowerPoint

and

traditional

lectures.

Computers

&

Education.

2009;52:858-67.

2.

Shu'aibu

B,

Bappah

AS,

Saud

MSB.

Modelling

ICT

Integration

in

Teaching

and

Learning

of

Technical

Education.

Journal

of

Social

Sciences.

2013;9(2):81-8.

3.

Littlefield

MB,

Rubinstein

K,

Pittman

ME.

Beyond

PowerPoint™:

Using

Learning

Objects

to

Enhance

Social

Work

Courses.

Journal

of

Technology

in

Human

Services.

2015;33(2):172-90.

4.

Can

AV,

Karaca

N,

Akyel

N,

Demirci

SD.

Evaluating

the

Fitness

of

Lecturing

with

Powerpoint

Presentations

for

Accounting

Education-

Research

at

Sakarya

University-.

Procedia

-

Social

and

Behavioral

Sciences.

2012;55:128

-

37.

5.

Raman

R,

Pramod

D,

Bharathi

V.

Information

and

Communication

Technology

Based

Model

for

Dematerialization

of

Academic

Certificates

for

Indian

Educational

System.

American

Journal

of

Applied

Sciences.

2014;11(1):85-8.

6.

Kosslyn

SM,

Kievit

RA,

Russell

AG,

Shephard

JM.

PowerPoint

Presentation

Flaws

and

Failures:

A

Psychological

Analysis.

Frontiers

in

Psychology.

2012;3:230.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC3398435.

7.

Liu

X,

Xu

Y,

Pange

J.

Teachers'

use

of

PowerPoint

in

kindergarten:

An

empirical

investigation

in

China.

Education

and

Information

Technologies.

2016;21(2):425-41.

8.

Hashemi

M,

Azizinezhad

M,

Farokhi

M.

Power

Point

as

an

innovative

tool

for

teaching

and

learning

in

modern

classes.

Procedia

-

Social

and

Behavioral

Sciences.

2012;31:559

-

63.

9.

Kahraman

S,

Çevik

C,

Kodan

H.

Investigation

of

university

students'

attitude

toward

the

use

of

powerpoint

according

to

some

variables.

Procedia

Computer

Science.

2011;3:1341-7.

10.

MOKHTAR

AE,

ELMUSTAFA

SDA.

Evaluation

of

Power

Point

Presentation

Reflection

Among

Students

of

Applied

Medical

Sciences

College,

Najran

University.

The

FASEB

Journal.

2016;30(1

Supplement):785.20.

11.

Uz

Ç,

Orhan

F,

Bilgiç

G.

Prospective

teachers'

opinions

on

the

value

of

PowerPoint

presentations

in

lecturing.

Procedia

Social

and

Behavioral

Sciences.

2010;2:2051-9.

12.

Wecker

C.

Slide

presentations

as

speech

suppressors:

When

and

why

learners

miss

oral

information.

Computers

&

Education.

2012;59:260-73.

13.

Akhlaghi

M,

Zareian

G.

The

Effect

of

PowerPoint

Presentation

on

Grammar

and

Vocabulary

Learning

of

Iranian

Pre-University

EFL

Learners.

Academic

Research

International.

2015;6(1):160.

14.

Tufte

ER.

The

cognitive

style

of

PowerPoint:

Graphics

Press

Cheshire,

CT;

2003.

15.

Tufte

ER.

PowerPoint

is

Evil.

PowerPoint

Corrupts.

PowerPoint

Corrupts

Absolutely.

Wired

Magazine.

2003;11(9):118-9.

16.

Taylor

D.

Death

by

PowerPoint.

Developmental

Medicine

&

Child

Neurology.

2007;49(5):395-.

18.

Thompson

C.

PowerPoint

makes

you

dumb.

New

York

Times,

December.

2003;14.

19.

Barnes

J,

Patterson

B.

A

Necessary

Evil:

Edward

Tufte

and

Making

the

Best

of

PowerPoint.

American

Society

of

Trial

Consultants,

The

Jury

Expert.

2011;23(6).

20.

Holmes

N.

The

Profession:

In

Defense

of

PowerPoint.

Computer.

2004:89-100.

21.

Penciner

R.

Does

PowerPoint

enhance

learning?

CJEM.

2013;15(2):109-12.

22.

Hawker

CJ.

Editorial:

Effective

Presentations-A

Must.

Angewandte

Chemie

International

Edition.

2013;52(14):3780-1.

23.

Kollar

J,

Babusa

B,

Stauder

A,

Pilling

J,

Cserepes

R,

Czeglédi

E.

Improving

teaching

efficiency

on

Medical

Universities

-

A

comparative

study

of

Hungarian

and

foreign

medical

university

students'

feedbacks

regarding

learning

by

KOLLAR

method.

J

Contemp

Med

Edu.

2016;4(1):1-7.

24.

Stein

K.

The

Dos

and

Don'ts

of

PowerPoint

Presentations.

Journal

of

the

American

Dietetic

Association.

2006:1745.

25.

Roos

D,

Toothman

J.

10

Tips

for

More

Effective

PowerPoint

Presentations

2008.

Available

from:

http://money.howstuffworks.com/business-communications/effective-powerpoint-presentations.htm.

26.

Collins

J.

Education

Techniques

for

Lifelong

Learning\

Giving

a

PowerPoint

Presentation:

The

Art

of

Communicating

Effectively.

RadioGraphics.

2004;24(4):1185-92.

27.

Bourne

PE.

Ten

Simple

Rules

for

Making

Good

Oral

Presentations.

PLoS

Computational

Biology.

2007;3(4):0593-4.

28.

Pros

RC,

Tarrida

AC,

Martin

MdMB,

Amores

MdCC.

Effects

of

the

PowerPoint

methodology

on

content

learning.

Intangible

Capital.

2013;9(1):184-98.

29.

Craig

RJ,

Amernic

JH.

PowerPoint

Presentation

Technology

and

the

Dynamics

of

Teaching.

Innov

High

Educ.

2006;31:147-60.

30.

Pourfarhad

M,

Azmey

FLA,

Hassani

L.

Perceptions

of

International

Students

on

Academic

Literacy

Focusing

on

Speaking

and

Listening

Skills

in

Malaysia.

Procedia

-

Social

and

Behavioral

Sciences.

2012;69:197-205.

31.

Blokzijl

W,

Andeweg

B,

editors.

The

Effects

of

Text

Slide

Format

and

Presentational

Quality

on

Learning

in

College

Lectures.

IEEE

International

Professional

Communication

Conference;

2005:

IEEE.

32.

Alexandrov

AV,

Hennerici

MG.

How

to

Prepare

and

Deliver

a

Scientific

Presentation.

Cerebrovascular

Diseases

2013;35(3):202-8

33.

Fathalla

MF,

editor.

A

Practical

Guide

for

Health

Researchers.

Cairo:

WHO

Regional

Publications

Eastern

Mediterranean

Series

30;

2004.

34.

Castillo

M.

Making

a

Point:

Getting

the

Most

Out

of

PowerPoint.

AJNR

Am

J

Neuroradiol.

2011

(32):217-20.

35.

O'Neil

S.

PowerPoint

Presentation

Dos

&

Don'ts:

Steve

O'Neil;

2005

[27-9-2013].

36.

Collins

J.

Education

Techniques

for

Lifelong

Learning

-

Making

a

PowerPoint

Presentation.

RadioGraphics.

2004;24(4):1177-83.

37.

Durso

FT,

Pop

VL,

Burnett

JS,

Stearman

EJ.

Evidence-Based

Human

Factors

Guidelines

for

PowerPoint

Presentations.

Ergonomics

in

Design.

2011;19(4):4-8.

38.

Brodsky

D,

Doherty

EG.

Educational

Perspectives:

Creating

an

Effective

PowerPoint

Presentation.

Neoreviews

[Internet].

2011;

12(e687).

Available

from:

http://neoreviews.aappublications.org/content/12/12/e687.

39.

Garner

JK.

Rethinking

the

Design

of

Presentation

Slides:

An

Evidence

Based

Approach

2013.

Available

from:

http://www.teachingkb.cidde.pitt.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Garner_Handout_SIDI_2013.pdf.

40.

Berk

RA.

Top

10

Evidence-Based,

Best

Practices

for

PowerPoint®

in

the

Classroom.

Transformative

Dialogues:

Teaching

&

Learning

Journal.

2012;5(3):1-7.

41.

Jones

AM.

The

use

and

abuse

of

PowerPoint

in

Teaching

and

Learning

in

the

Life

Sciences:

A

Personal

Overview.

Bioscience

Education.

2003;2(1):1-13.

42.

Cho

YH,

Lee

SE.

The

role

of

co-explanation

and

self-explanation

in

learning

from

design

examples

of

PowerPoint

presentation

slides.

Computers

&

Education.

2013;69:400-7.

43.

Berk

RA.

How

to

Create

"Thriller"

PowerPoints®

in

the

Classroom.

Innov

High

Educ.

2012;37:141-52.

44.

Singh

D,

Omar

R,

Anuar

A.

Low

Cost

Interactive

Electronic

Whiteboard

Using

Nintendo

Wii

Remote.

American

Journal

of

Applied

Sciences.

2010;7(11):1458-63.

45.

Kelleher

C,

Wagener

T.

Ten

guidelines

for

effective

data

visualization

in

scientific

publications.

Environmental

Modelling

&

Software.

2011;26:822-7.

46.

Brock

S,

Joglekar

Y.

Empowering

PowerPoint:

Slides

and

teaching

effectiveness.

Interdisciplinary

Journal

of

Information,

Knowledge,

and

Management.

2011;6(1):85-94.

47.

Parker

I.

Absolute

PowerPoint:

Can

a

software

package

edit

our

thoughts.

The

New

Yorker

28

May

2001:76-87.

48.

Dawson

V,

Forster

P,

Reid

D.

Information

Communication

Technology

(ICT)

Integration

in

a

Science

Education

Unit

for

Preservice

Science

Teachers;

Students'

Perceptions

of

Their

ICT

Skills,

Knowledge

and

Pedagogy.

International

Journal

of

Science

and

Mathematics

Education.

2006;4(2):345-63.

49.

Berk

RA.

Research

on

PowerPoint®:

From

basic

features

to

multimedia.

International

Journal

of

Technology

in

Teaching

and

Learning.

2011;7(1):24-35.

50.

Chopra

J,

Rani

A,

Rani

A,

Deewan

R,

Srivastava

A,

Sharma

P.

Students'

Reflections

on

Teaching

Methodology

in

Anatomy.

Asian

Journal

of

Medical

Sciences.

2013;5(1):47-51

|