|

Storage of Medicines

and Temperature Control at Community Pharmacies

in Rural District of Sindh, Pakistan: An Exploratory

Cross-Sectional Study

Nadir Suhail

(1)

Sumera Aziz Ali (2)

Waris Qidwai (3)

Savera Aziz Ali (4)

Saleem Iqbal (2)

Yousaf Memon (2)

Mohammad Masood Kadir(2)

(1) Monitoring and Evaluation consultant deliver

project USAID, Pakistan

(2) Department of Community Health Sciences

Aga Khan University, Karachi Pakistan

(3) Department of Family medicine Aga Khan University,

Karachi Pakistan

(4) School of Nursing Aga Khan University, Karachi

Pakistan

Correspondence:

Dr. Waris Qidwai

Professor and Chairman,

Family Medicine Department

Aga Khan University Karachi Pakistan

Tel: (92-21) 486-4843, 486-4814

Fax: (92-21) 493-4294, 493-2095

Email: waris.qidwai@aku.edu

|

Abstract

Background: Medicines

are the essential tools for prevention,

cure and control of diseases. If these

medicines are ineffective then their aftermath

can cause wastage of resources. Medicines

lose their required effectiveness due

to inadequate storage at required temperature.

Objective: The

objective was to estimate the proportion

of pharmacies with high temperature (>25°C)

inside pharmacy outlets in two talukas

(sub-districts) of district Thatta, Sindh

Methodology:

An exploratory cross sectional study

design was conducted from August 2013

to August 2014. All pharmacies of the

two talukas were approached by doing a

census. Descriptive analysis was done

to calculate the frequencies and proportions.

Results: All pharmacies (n=62)

had a temperature of >25?C inside the

pharmacies. Medicines were exposed to

sunlight in 39 (63%) of the pharmacies

and 39 (63%) of pharmacies had refrigerators

to keep insulin and vaccines. Median duration

of electricity shut downs was 12 hours

per day and 11% of the pharmacies had

back up power supply.

Conclusion: More than a quarter

of pharmacy owners were aware about maintaining

the required temperature of < 25?C

but none of them were maintaining required

temperature. Considering the electricity

shut down, it is important to make cost

effective and long term strategies to

maintain the efficacy of medicines. Proper

legislation needs to be enforced with

continuing training programs for pharmacy

owners. Further research is required to

explore different ways of maintaining

required temperature to ensure the adequate

efficacy of medicines.

Key words:

Pharmacy, Temperature control, Storage,

Medicines

|

Medicines including vaccines are considered

as one of the important tools in combating diseases

across the world, but these medicines may also

cause adverse events with varying severity which

usually depend upon patient as well as product

related factors(1). This issue is even more

critical in developing countries where most

medications are not stored at appropriate conditions

and can be easily purchased over the counter(1).

Medicinal products require appropriate storage

conditions in order to ensure the quality and

efficacy of medicines (2). Medicines which are

not stored on required temperature (< 25?

C) can further increase unnecessary burden on

economy of general population due to their ineffectiveness

in curing of disease (2).

Literature shows that stability of pharmaceutical

products is extremely essential to maintain

their therapeutic efficacy(3). Temperature plays

a key role to maintain the required efficacy

of medicines (4-6). It has been suggested that

more than 50% of medicines should be stored

on required temperature, which is usually less

than 25?C (6-8). Apart from high temperature

(> 25°C), direct exposure to sunlight

and improper management of medicines during

shipment can also cause damage to pharmaceutical

products like antivirals, multi-vitamins, acetaminophens,

antibiotics, diuretics, hydrocortisone, eye

drops, analgesics, anti-depressants and latex

products such as male condoms (9, 10). Light

can change the properties of different materials

and products. This change in properties can

be due to steadily increasing exposure of medicines

to high temperature during storage or dispensing

the medicines at the pharmacies through different

mechanisms(11, 12).

Almost every country in the world has some

mechanism of providing drugs to people residing

in communities, either through proper prescription

or without prescription of medications. These

countries have retail and wholesale pharmacies

working regularly to serve their community (1).

likewise other countries, there are an estimated

45 000 to 50 000 wholesale and retail drug outlets

in Pakistan (1). Although there is a network

of health services in Pakistan's public sector,

and overabundance of private sector initiatives,

45% of the population still lacks access to

health services (13). Thus, in order to meet

health needs and to reduce out of pocket payment,

people rely on alternative health care systems

such as traditional medicine practitioners,

chemists, faith healers, and homeopaths(1).

Self-medication has been consistently increasing

due to large gaps in the formal health sector

of the country (1).

Furthermore, people usually rely on the nearby

accessible medical stores or small community

pharmacies to purchase medicines for different

diseases (14, 15). In many countries, community

pharmacies are places where people may obtain

health advice and assistance to manage their

disease states with required medications (16).

Moreover, these pharmacies are often the first

point of contact for patients seeking health

care as they are usually more accessible and

less socially distant than other providers including

medical doctors (1). Community pharmacies have

been considered as a key interface between the

health care system and the general public (14,

15). It is common that many workers at community

pharmacies are involved in providing health

advice on most of the health problems prevailing

in community (14, 15). Even most of the times,

community pharmacy workers prescribe medicines,

which are sometimes safe and effective when

used correctly, however these can become dangerous

in case of emergencies (17, 18). Community pharmacies

are perceived as an easy and convenient source

of advice, referral to nearby facility and source

of required information by the patients and

their families in developing world, including

Pakistan (19, 20).

Community pharmacy owners can be considered

as one of the important influential stakeholders

in health care system who can affect the drug

usage owing to their scale of operations and

placement in the healthcare delivery system

(21). Looking at importance of community pharmacies

and their outreach services, many developing

countries have used their potential to promote

safe and effective treatments (17). This has

been done by enhancing their dispensing practices

and management of medicines inside pharmacy

outlets and in stores, which are easily acceptable

to community pharmacy workers and their owners

(17).

In Pakistan unfortunately the area of community

pharmacy has been ignored by policymakers to

make collaboration of community pharmacy workers

and owners with other stake holders in health

sector of country for the betterment of population.

Therefore it is essential to work in team by

including community pharmacy workers for betterment

of general population (22)

Thus it is essential to know the importance

of community pharmacies in the context of temperature

management during hot weather and particularly

in rural areas of Pakistan (23).

Click here for

Figure 1: Storage Practices in retail Pharmacies

at District Level: A conceptual Framework

Furthermore, in Pakistan there is an issue of

increased electricity shut downs in rural areas

even for more than 12 hours which prevents storing

medicines at required temperature in community

pharmacies of rural areas of Pakistan. Community

pharmacies are one of the important sources

of dispensing medicines to the Pakistani population.

Knowledge about proper storage of medicines

at required temperature in community pharmacies

is not available. In country like Pakistan many

other issues also arise in hot weather and it

is a challenge to store the medicines appropriately

on required temperature due to electricity shut

downs and lack of backup power supply (23).

Thus, it is important to know that whether the

medicines are stored on required temperature

or not, particularly in community pharmacies

of rural areas.

This study had assessed the practices regarding

storage of medicines in rural area of Sindh,

Pakistan. This study was aimed to estimate the

proportion of pharmacies with high temperature

(> 25 °C) inside the pharmacy outlets

in Sindh Pakistan and to estimate the proportion

of pharmacies selling vaccines, insulin and

have refrigerators with and without backup power

supply. This information will contribute to

improve policies for managing and storing medicines

appropriately especially in remote areas of

Sindh.

Exploratory cross sectional study design was

used to conduct this study form August 2013

to August 2014. This study was conducted in

two areas of the Thatta district. These areas

included two talukas (sub-districts), Sujawal

and Jati. Thatta is a rural district in the

southernmost part of Sindh province in Pakistan,

bordering Karachi (24). The estimated population

of district is around 1513194 (25) with literacy

rate of 22.1% (26). There are five public sector

hospitals in Thatta, as well as 8 rural health

centers (RHCs) and 51 basic health units (BHUs).

Those community pharmacies which were selling

at least allopathic medicines in the two talukas

(sub-districts) of district Thatta (Sujawal

and Jati) and whose pharmacy owners gave the

written informed consent were included in this

study. While those pharmacies, which were located

in the hospital premises or where a medical

doctor was practicing were excluded from this

study.

We did a census for all pharmacies of two talukas

(sub-districts) to get the list of eligible

pharmacies. The census covered a total of 70

pharmacies and all 70 pharmacies and their pharmacy

owners or drug sellers were approached but 8

pharmacies refused to give the informed consent

thus could not be included in the study. Thus

62 pharmacies were included through consecutive

non-probability sampling.

Pharmacy owners were interviewed through a structured

and pretested questionnaire. A checklist was

also used to assess the storage conditions in

the community pharmacies during month of June

and July 2014. Room thermometer was used to

measure the temperature in all the selected

pharmacies. Three digital thermometers and three

mercury maximum/minimum thermometers were purchased

and checked by comparing these thermometers

with standard thermometer in biomedical department

of Aga Khan University for 20 hours. The biomedical

department engineers agreed within standard

deviation of 0.2°C. Two digital thermometers

along with mercury thermometers were placed

in every community pharmacy for half an hour.

One thermometer was kept in outer half of the

community pharmacy where first drug was placed

and one in inner half of the community pharmacy

along where last drug was placed. Over the same

period of time maximum ambient air temperature

of Karachi was also noted from website of Pakistan

meteorological department, whose results displayed

on different web pages. Three readings of the

temperature were taken at three different timings

of the day. The maximum temperature in the day

was recorded at 1500 hours of each day. After

taking the three readings, an average value

of all readings was taken to overcome the intra

rater bias.

Data was analyzed through SPSS version 19. Frequencies

and proportions were generated for all the variables.

Estimated prevalence of pharmacies with high

temperature (>25 °C) was calculated.

Descriptive statistics were computed for both

continuous and categorical variables. This study

was conducted only after ethical approval by

Ethical Review Committee (ERC) of the Aga Khan

University.

From

a

total

of

70

pharmacies,

62

pharmacy

owners

expressed

their

willingness

to

participate

in

the

study,

making

the

interview

response

rate

as

95%.

Median

duration

of

service

provision

by

pharmacy

owners

in

the

community

was

8

years

with

interquartile

range

(IQR)

of

6-10

years

(Table

1).

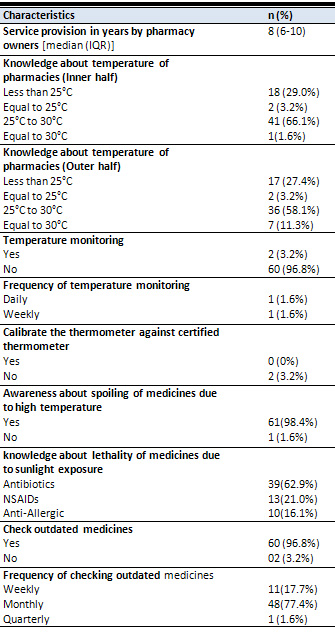

Table

1:

Knowledge

of

pharmacy

owners

about

temperature

and

storage

practices

(n=62)

With

respect

to

knowledge

about

temperature

of

pharmacies,

18

(29%)

of

the

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

temperature

of

inner

half

of

pharmacy

should

be

below

25

°C,

41

(66%)

reported

that

temperature

of

inner

half

of

pharmacy

should

be

between

25

°C

and

30

°C,

2

(3%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

temperature

should

be

equal

to

25°C,

and

1

(2%)

reported

that

temperature

should

be

equal

to

30°C.

With

respect

to

the

temperature

of

outer

half

of

pharmacy,

17

(27%)

of

the

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

temperature

should

be

less

than

25°C,

36

(58%)

pharmacy

owners

said

that

it

should

be

between

25°C

and

30°C,

7

(11%)

owners

reported

that

temperature

should

be

equal

to

30°C,

while

2

(3%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

temperature

should

be

equal

to

25°C.

Regarding

temperature

monitoring,

2

(3%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

they

used

to

monitor

the

temperature

of

main

pharmacy

with

a

room

thermometer

but

none

of

them

used

to

maintain

the

temperature

of

storage

area

up

to

required

level.

Out

of

these

2

pharmacies,

1

(2%)

pharmacy

owner

reported

to

monitor

the

temperature

on

a

daily

basis

while

1(2%)

reported

to

monitor

the

temperature

on

a

weekly

basis.

None

of

them

used

to

calibrate

the

thermometer

against

the

certified

thermometer

(Table

1).

Regarding

the

knowledge

about

toxic

effects

of

medicines

due

to

sunlight

exposure,

39

(63%)

of

the

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

antibiotics

can

become

ineffective

if

exposed

to

sunlight,

followed

by

13

(21%)

owners

indicating

NSAIDS

become

ineffective

upon

sunlight

exposure

(Table

1).

Out

of

62

pharmacies,

30

(48%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

selling

of

insulin;

all

of

them

used

to

keep

the

insulin

in

refrigerators.

Sixteen

(26%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

selling

of

vaccines

and

keeping

them

in

refrigerators.

Regarding

electricity

shut

down,

all

owners

reported

that

they

face

this

problem

in

their

respective

talukas;

its

median

duration

being

12

hours

per

day

(IQR:

12-14hrs)

but

only

7

(11%)

pharmacies

had

a

backup

supply

of

power

(Table

2).

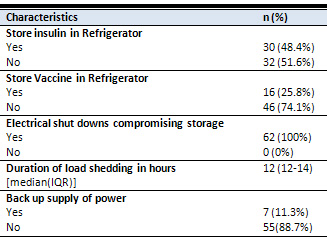

Table

2:

Storage

practices

of

the

medicines

required

to

be

stored

in

cool

place

(n=62)

Furthermore,

35

(56%)

pharmacies

were

found

to

have

items,

grouped

in

amounts

that

are

easy

to

count.

With

respect

to

expired

medicines,

all

62

pharmacy

owners

used

to

keep

the

items

with

short

expiry

dates

in

front,

while

those

medicines

which

had

long

expiry

date

were

placed

at

the

back

("first

expired

first

out"

principle).

9

(15%)

pharmacies

were

maintaining

the

record

for

the

removal

of

items

including

date,

time,

witness

and

manner

of

removal

(Table

3).

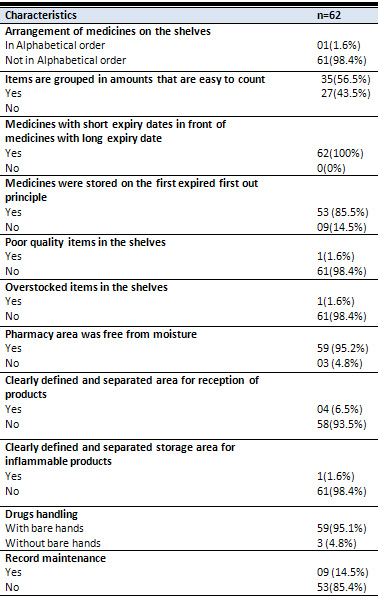

Table

3:

Findings

regarding

storage

of

medicines

in

main

pharmacy

Approximately

1.6%

of

the

pharmacies

were

found

to

have

the

poor

quality

items

in

the

shelves

and

similar

proportion

had

any

overstocked

items

in

the

shelves

(Table

3).

Moreover,

the

floors,

walls,

sinks,

benches,

shelves,

containers

and

dispensing

bottles

were

found

to

be

clean

in

about

59

(95%)

pharmacies.

Only

4

(6%)

pharmacies

had

a

clearly

defined

area

for

reception

of

products,

and

3

(5%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

drugs

are

not

handled

with

bare

hands

(Table

3).

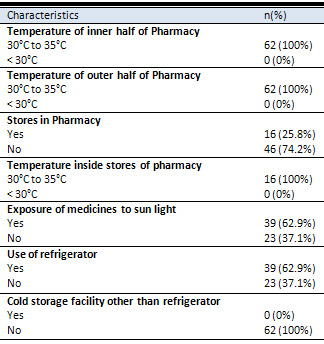

All

of

the

62

pharmacies

(100%)

had

a

temperature

of

>25°C

(Table

4).

In

39

(63%)

pharmacies,

sunlight

exposure

to

medicines

was

evident.

Among

the

medicines

exposed

to

sunlight,

NSAIDs

comprised

the

major

proportion

(51.2%),

followed

by

antibiotics

(38.4%)

and

multivitamins

(20.5%).

Similarly,

39

(63%)

pharmacies

had

refrigerators

to

keep

the

important

medicines

in

cool

environment

but

only

2

(3%)

pharmacies

had

temperature-monitoring

devices

(Table

4).

None

of

the

pharmacies

had

a

cold

storage

facility

other

than

the

refrigerator.

Table

4:

Findings

regarding

the

temperature

of

community

pharmacies

(Objective

assessment)

(n=62)

Out

of

62

pharmacy

owners,

16

(26%)

had

a

separate

storage

area

within

the

main

pharmacy

and

in

these

areas

the

temperature

was

found

to

be

more

than

25

°C.

Approximately

8

(13%)

pharmacy

owners

reported

that

the

store

is

large

enough

to

keep

all

the

supplies.

Around

11

(18%)

pharmacies

had

a

storage

room

which

was

reserved

only

for

pharmacy

related

functions,

and

7

(11%)

had

adequate

storage

capacity

in

the

warehouse

for

medicines

and

medical

supplies.

Moreover,

in

6

(10%)

pharmacies,

the

stores

were

in

good

condition.

One

(2%)

pharmacy

was

found

to

have

a

store

with

cracks,

holes

and

signs

of

water

leakage.

In

9

(15%)

pharmacies,

the

stores

had

a

ceiling

in

from

which

5

(8%)

were

not

in

good

condition.

In

2

(3%)

pharmacies,

the

stores

were

properly

ventilated

with

appropriate

air

entry.

Stores

of

7

(11%)

pharmacies

were

tidy

with

clean

shelves,

walls

and

did

not

have

signs

of

any

infestation.

Furthermore,

15%

of

the

stores

did

not

have

any

expired

items

in

their

storage

area

(Table

5).

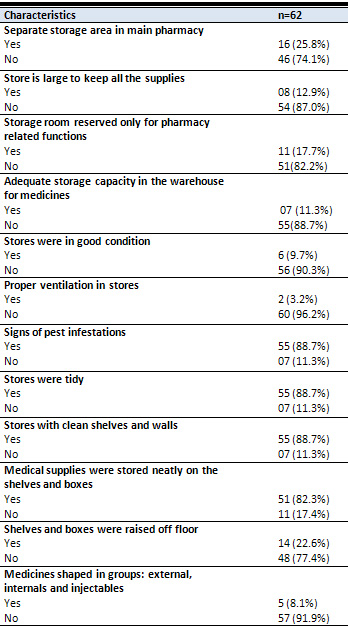

Table

5:

Findings

regarding

storage

of

medicines

in

separate

storage

area

of

main

Pharmacy

Medical

supplies

were

stored

neatly

on

the

shelves

and

boxes

in

82%

of

the

pharmacies

but

shelves

and

boxes

were

raised

off

the

floor

in

only

23%

of

the

pharmacies.

In

5

(8%)

pharmacies,

the

supplies

were

categorized

in

various

groups.

None

of

the

pharmacy

owners

had

practice

of

storing

the

controlled

substances

in

double

locked

storage

space

(Table

5).

Exposure

of

medicines

to

high

temperature

in

storage

or

in

transport

could

reduce

their

efficacy

of

drugs

including

vaccines(11).

The

major

factors

which

contribute

to

decreased

efficacy

of

medicines

after

quality

manufacturing

are

improper

storage

of

medicines

at

undesirable

temperature

(22).

The

journey

of

medicines

begins

at

the

site

of

manufacturer

and

passes

through

warehouses,

pharmacies

and

sometimes

other

environments

before

reaching

the

end

user

(20).

Temperature

conditions

in

earlier

stages

have

received

attention,

but

little

work

has

been

done

in

primary

care

settings

and

community

pharmacy

settings,

both

in

developed

and

developing

countries

(20).

The

findings

of

present

study

suggest

that

majority

of

pharmacy

owners

had

knowledge

about

correct

temperature

for

storing

medicines

at

that

temperature

(<25?C)

but

almost

100%

of

the

community

pharmacies

were

having

temperature

(>25?C)

degree

centigrade,

which

is

more

than

the

required

temperature

for

storing

medicines

safely.

In

both

environments

i.e.

outer

and

inner

half

of

pharmacies,

medicines

were

exposed

to

temperature

greater

than

(>25?C).

These

findings

suggest

that

there

is

huge

gap

between

knowledge

of

pharmacy

owners

and

their

practices

because

on

one

hand

they

highlighted

that

high

temperature

(>25?C)

can

affect

quality

of

medicines

and

on

other

hand

temperature

control

at

required

level

(<25?C)

is

not

ensured

in

community

pharmacies

of

these

rural

areas.

Moreover,

these

findings

are

supported

by

the

fact

that

medicines

were

directly

exposed

to

sunlight

in

63%

of

the

community

pharmacies.

These

findings

are

consistent

with

other

studies

around

the

world

(20).

Our

study

also

examined

storage

practices

in

the

community

pharmacies.

Although,

63%

of

the

pharmacies

had

a

refrigerator

to

keep

the

medicines

in

a

cool

environment

but

due

to

incessant

electricity

shut

downs

(estimated

to

be

approximately

12

hours

per

day),

and

limited

backup

power

supply,

may

render

these

medicines

ineffective.

Our

study

reveals

that

3%

of

the

pharmacies

were

having

a

temperature

monitoring

facility

or

device.

With

a

dearth

of

temperature

monitoring

devices,

excessive

electric

cut-offs

and

limited

alternative

power

supply

for

refrigeration,

and

may

potentiate

doubt

on

the

efficacy

of

medicines.

These

findings

were

consistent

with

that

reported

from

Banglore,

India

(27).

These

findings

of

having

refrigerator

and

temperature

monitoring

facility

were

slightly

different

from

the

study

findings

conducted

by

Zahid

A

Bhutt

et

al

in

Urban

Rawalpindi

in

2005,

where

majority

(76%)

of

the

pharmacy

owners

had

refrigerator

and

10%

of

these

pharmacies

had

temperature

monitoring

devices

as

well(28).

The

difference

in

findings

of

having

refrigerator

in

current

study

might

be

due

to

setting

of

the

study

in

the

rural

district

of

Sindh

where

worth

of

purchasing

refrigerator

might

not

be

considered

as

compared

to

urban

areas.

Moreover,

due

to

frequent

electricity

cut-

offs,

pharmacy

owners

might

not

prefer

to

invest

in

purchasing

the

refrigerator

or

they

might

not

have

the

knowledge

of

keeping

the

required

medicines

in

the

refrigerator.

Around

25%

of

the

pharmacies

were

selling

vaccines

and

all

of

these

pharmacies

were

storing

the

vaccines

in

refrigerator,

despite

limitations

of

maintaining

the

desired

temperature.

These

findings

were

different

from

the

studies

conducted

in

Karachi

and

Rawalpindi,

where

more

than

half

of

the

pharmacy

owners

were

selling

vaccines

irrespective

of

appropriate

storage

practices(28,

29).

This

difference

might

be

due

to

difference

in

demand

and

supply

of

rural

and

urban

areas.

In

urban

areas,

community

people

might

be

aware

about

and

might

give

high

importance

of

preventive

aspect

of

the

health

therefore

there

would

be

more

demand

for

vaccines,

which

might

be

satisfied

by

equal

supply

by

community

pharmacies

in

urban

areas.

Furthermore,

our

study

also

found

that

commonly

used

medicines

like

NSAIDs,

multivitamins

and

antibiotics

were

exposed

to

direct

sunlight

and

studies

have

also

shown

that

such

medicines

show

significant

reductions

in

activity

when

stored

at

temperature

more

than

25oC

(20).

Furthermore,

studies

have

also

shown

that

dissolution

rate

of

diclofenac

sodium

(NSAIDs)

tablets

significantly

reduces

in

as

little

as

three

months

following

exposure

to

high

ambient

temperature(20).

Although

the

community

pharmacy

owners

had

knowledge

about

the

adverse

effects

of

high

temperature

on

medicines

but

they

could

not

modify

the

temperature

of

community

pharmacies

alone

due

to

multiple

barriers

like

lack

of

air

conditioning

system,

load

shedding

problems

and

lack

of

backup

power

supply

in

community

pharmacies.

Moreover,

there

might

be

other

barriers

or

factors

which

might

have

stopped

community

pharmacy

owners

or

drug

sellers

to

maintain

the

required

temperature

in

their

respective

pharmacies

and

there

is

strong

need

to

explore

such

barriers

in

future

studies.

Since

pharmacies

are

often

the

first

point

of

interaction

for

patients

looking

for

health

care

as

they

are

usually

more

reachable

and

less

socially

distant

than

other

health

care

providers,

including

general

physicians

and

consultants.

Therefore,

if

drugs

or

vaccines

are

compromised

by

quality

issues

such

as

improper

storage

of

medicines

at

undesirable

temperature

then

community

people

may

end

up

with

products

or

instructions

that

are

useless

and

even

dangerous

for

the

community

as

a

whole(28).

In

fact,

it

has

been

said

that

if

a

physician's

medical

error

could

terminate

a

life,

then

a

singular

error

from

the

drug

manufacturer

or

dealer

can

most

certainly

lead

to

the

loss

of

many

lives(30).

| STRENGTHS

AND

LIMITATIONS

OF

THE

STUDY

|

There

is

a

scarcity

of

literature

regarding

the

storage

practices

of

medicines

in

community

pharmacies,

particularly

in

rural

areas

of

Pakistan.

Therefore,

to

the

best

of

our

knowledge

this

was

the

first

study

of

its

kind

that

has

assessed

the

temperature

and

storage

practices

of

medicines

in

community

pharmacies

in

rural

district

of

Sindh,

Pakistan.

Temperature

was

measured

objectively

with

the

standard

procedure

to

avoid

the

measurement

bias.

In

addition

to

this,

study

findings

can

be

generalized

to

rural

areas

of

developing

countries.

The

scope

of

this

study

was

limited

to

pharmacy

owners

and

drug

inspectors

but

perceptions

of

owners

of

pharmaceutical

companies,

other

government

authorities,

community

stakeholders

and

policy

makers

could

not

be

assessed.

The

collection

of

data

was

limited

to

only

two

talukas.

Interviewer

bias

might

be

there

due

to

nature

of

questions

being

asked

from

pharmacy

owners.

The

study

found

more

than

a

quarter

of

pharmacy

owners

had

knowledge

about

maintaining

the

required

temperature

of

<

25°C

but

none

of

the

pharmacies

in

the

catchment

area

were

maintaining

required

temperature

of

<

25°C.

We

also

concluded

that

storage

practices

in

community

pharmacies

/

medicine

stores

were

found

to

be

poor

and

very

few

pharmacy

owners

were

monitoring

temperature

in

their

pharmacies.

Although

there

were

some

observed

insignificant

cases

of

satisfactory

storage

practices

amongst

community

pharmacies/

medicine

stores,

nevertheless

the

evidently

generally

poor

storage

practices

weighed

higher

because

of

their

potential

untoward

chain

effects

on

drug

consumers.

Moreover,

looking

at

the

median

duration

of

load

shedding

and

limited

backup

power

supply,

it

is

very

important

to

make

cost

effective

and

long

lasting

strategies

to

maintain

the

safety,

efficacy

of

medicines

and

to

improve

quality

of

medicines

especially

in

remote

areas.

Strict

monitoring

and

regulation

of

these

pharmacies

are

required.

Such

storage

practices

should

also

be

evaluated

at

homes

to

see

that

how

people

store

these

medicines

in

their

households.

Furthermore,

there

is

a

need

to

enforce

existing

legislation

with

ongoing

training

programs

directed

towards

pharmacy

owners

and

drug

sellers

and

to

involve

the

pharmaceutical

industry,

which

plays

an

important

role

in

influencing

pharmacy

practices

of

pharmacy

owners.

In

future,

more

research

is

required

to

explore

the

different

ways

of

maintaining

the

required

storage

conditions

of

medicines

to

ensure

the

adequate

efficacy,

safety

and

effectiveness

of

medicines.

1.

Butt

ZA

GA,

Nanan

D,

Sheikh

AL,

White

F.

Quality

of

pharmacies

in

Pakistan:

a

cross-sectional

survey.

International

Journal

for

Quality

in

Health

Care.

2005;17(4):307-13.

2.

Hafeez

A,

Kiani

AG,

Din

Su,

Muhammad

W,

Butt

K,

Shah

Z,

et

al.

Prescription

and

Dispensing

Practices

in

Public

Sector

Health

Facilities

in

Pakistan-Survey

Report.

JOURNAL-PAKISTAN

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION.

2004;54(4):187-91.

3.

Thome

J-M

PSL.

People's

Democratic

Republic:

health

financing

reform

and

challenges

in

expanding

the

current

social

protection

schemes.

Promoting

Sustainable

Strategies

to

Improve

Access

to

Health

Care

in

the

Asian

and

Pacific

Region.

2009:71-102.

4.

Du

B,

Daniels

VR,

Vaksman

Z,

Boyd

JL,

Crady

C,

Putcha

L.

Evaluation

of

physical

and

chemical

changes

in

pharmaceuticals

flown

on

space

missions.

The

AAPS

journal.13(2):299-308.

5.

Abegunde

D.

Essential

Medicines

for

Non-Communicable

Diseases

(NCDs)

and

pharmaceutical

policies

by

WHO.

2013.

6.

Butt

ZA,

Gilani

AH,

Nanan

D,

Sheikh

AL,

White

F.

Quality

of

pharmacies

in

Pakistan:

a

cross-sectional

survey.

International

Journal

for

Quality

in

Health

Care.

2005;17(4):307-13.

7.

Azhar

HUSSAIN

MIMI.

Qualification,

knowledge

and

experience

of

dispensers

working

at

community

pharmacies

in

Pakistan

Original

Research.

may

2011.

8.

Bott

RF,

Oliveira

WP.

Storage

conditions

for

stability

testing

of

pharmaceuticals

in

hot

and

humid

regions.

Drug

development

and

industrial

pharmacy.

2007;33(4):393-401.

9.

Pau

AK,

Moodley

NK,

Holland

DT,

Fomundam

H,

Matchaba

GU,

Capparelli

EV.

Instability

of

lopinavir/ritonavir

capsules

at

ambient

temperatures

in

sub-Saharan

Africa:

relevance

to

WHO

antiretroviral

guidelines.

Aids.

2005;19(11):1233.

10.

Hogerzeil

HV,

Battersby

A,

Srdanovic

V,

Stjernstrom

NE.

Stability

of

essential

drugs

during

shipment

to

the

tropics.

BMJ:

British

Medical

Journal.

1992;304(6821):210.

11.

Arshad

A,

Riasat

M,

Mahmood

MKT.

Drug

Storage

Conditions

in

Different

Hospitals

in

Lahore.

Journal

of

Pharmaceutical

Sciences

and

Technology.3(1):543-47.

12.

Crichton

B.

Keep

in

a

cool

place:

exposure

of

medicines

to

high

temperatures

in

general

practice

during

a

British

heatwave.

JRSM.

2004;97(7):328-9.

13.

Mahbub-ul-Haq.

Human

Development

in

South

Asia,Oxford

University

Press.

Karachi;

1998.

14.

Corelli

RL,

Zillich

AJ,

de

Moor

C,

Giuliano

MR,

Arnold

J,

Fenlon

CM,

et

al.

Recruitment

of

community

pharmacies

in

a

randomized

trial

to

generate

patient

referrals

to

the

tobacco

quitline.

Research

in

Social

and

Administrative

Pharmacy.9(4):396-404.

15.

Rafie

S,

Kim

GY,

Lau

LM,

Tang

C,

Brown

C,

Maderas

NM.

Assessment

of

Family

Planning

Services

at

Community

Pharmacies

in

San

Diego,

California.

Pharmacy.1(2):153-9.

16.

Farris

KB

F-LF,

Benrimoj

SIC.

Pharmaceutical

care

in

community

pharmacies:

practice

and

research

from

around

the

world.

Annals

of

Pharmacotherapy.

2005;39(9):1539-41.

17.

Adepu

R

NB.

General

practitioners\'

perceptions

about

the

extended

roles

of

the

community

pharmacists

in

the

state

of

Karnataka:

.

A

study

Ind

J

Pharma

Sci.

2006;

68:

36-40.

18.

Organization.

WH.

Role

of

Dispensers

in

Promoting

Rational

Drug

Use.

2000

19.

Qidwai

W

et

al.

Private

drug

sellers

education

in

improving

prescribing

practices.

J

Col

Physic

Surg

Pak

2006

16:

743-6.

20.

Viberg

N.

Selling

Drugs

or

Providing

Health

Care?:

The

role

of

private

pharmacies

and

drugstores,

examples

from

Zimbabwe

and

Tanzania.

Institutionen

fÃr

folkhälsovetenskap/Department

of

Public

Health

Sciences;

2009.

21.

Jacobs

S,

Hassell

K,

Ashcroft

D,

Johnson

S,

O’Connor

E.

Workplace

stress

in

community

pharmacies

in

England:

associations

with

individual,

organizational

and

job

characteristics.

Journal

of

health

services

research

&

policy.19(1):27-33.

22.

Bell

KN,

Hogue

CJR,

Manning

C,

Kendal

AP.

Risk

factors

for

improper

vaccine

storage

and

handling

in

private

provider

offices.

Pediatrics.

2001;107(6):e100-e.

23.

Patel

KT,

Chotai

NP.

Pharma

science

monitor.

Int

J

Pharm

Sci.1980-93.

24.

NoorAli

R,

Luby

S,

Rahbar

MH.

Does

use

of

a

government

service

depend

on

distance

from

the

health

facility?

Health

policy

and

planning.

1999;14(2):191-7.

25.

World

Health

O.

hepatitis

B.

2002.

26.

Enemuor

SC,

Atabo

AR,

Oguntibeju

OO.

Evaluation

of

microbiological

hazards

in

barbershops

in

a

university

setting.

Scientific

Research

and

Essays.

2012;7(9):1100-2.

27.

Sudarshan

MK

SM,

Girish

N,

Narendra

S,

Patel

NG.

An

evaluation

of

cold

chain

system

for

vaccines

in

Bangalore.

Indian

J

Pediatr.

1994;61:173-8.

28.

ZAHID

A.

BUTT

AHG,

DEBRA

NANAN,

ABDUL

L.

SHEIKH

AND

FRANK

WHITE.

Quality

of

pharmacies

in

Pakistan:

a

cross-sectional

survey.

International

Journal

for

Quality

in

Health

Care.

2005;17(4):307-13.

29.

Rabbani

F

CF,

Talati

N.

Behind

the

counter:

pharmacies

and

dispensing

patterns

of

pharmacy

attendants

in

Karachi.

Journal

of

Pakistan

Medical

Association.

2001;51:149-54.

30.

N.

C.

Obitte

AC,

D.

C.

Odimegwu

and

V.C.

Nwoke.

Survey

of

drug

storage

practice

in

homes,

hospitals

and

patent

medicine

stores

in

Nsukka,

Nigeria.

Scientific

Research

and

Essay.

November,

2009;4(11):1354-9.

|