|

Left renal atrophy in

sickle cell diseases

Mehmet Rami

Helvaci (1)

Ramazan Davran (2)

Mursel Davarci (3)

Orhan Ekrem Muftuoglu (4)

Lesley Pocock (5)

(1) Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

Antakya, Professor of Internal Medicine, M.D.

(2) Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

Antakya, Assistant Professor of Radiology, M.D.

(3) Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

Antakya, Associated Professor of Urology, M.D.

(4) Medical Faculty of the Dicle University,

Diyarbakir, Professor of Internal Medicine,

M.D.

(5) Lesley Pocock, medi+WORLD International,

Australia

Correspondence:

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, M.D.

Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

31100, Serinyol, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey

Phone: 00-90-326-2291000 (Internal 3399) Fax:

00-90-326-2455654

Email: mramihelvaci@hotmail.com

|

Abstract

Background: We

tried to understand whether or not there

is a difference in occurrence of renal

atrophy between the left and right sides

in sickle cell diseases (SCDs).

Methods: All

patients with SCDs were enrolled into

the study.

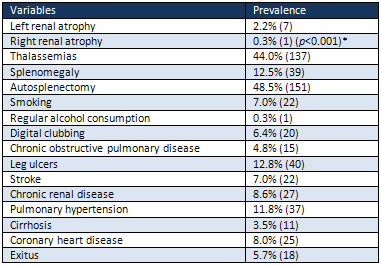

Results: The

study included 311 patients (153 females).

There were seven cases (2.2%) with left

renal atrophy against one case (0.3%)

with right renal atrophy (p<0.001).

Associated thalassemias were detected

in 44.0% and splenomegaly in 12.5% of

the patients. There was digital clubbing

in 6.4%, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease in 4.8%, leg ulcers in 12.8%,

stroke in 7.0%, chronic renal disease

in 8.6%, pulmonary hypertension in 11.8%,

cirrhosis in 3.5%, coronary heart disease

in 8.0%, and exitus in 5.7% of the patients.

Conclusion:

Renal atrophy is significantly higher

on the left side in SCDs. Splenomegaly

induced flow disorders in left renal vessels,

structural anomalies of the left renal

vein including nutcracker syndrome and

passage behind the aorta, and possibly

the higher arterial pressure of left kidney

due to the shorter distance to heart as

an underlying cause of endothelial damage

induced atherosclerosis, may be some of

the possible causes. Because of the higher

prevalences of left varicocele probably

due to drainage of left testicular vein

into the left renal vein, high prevalences

of associated thalassemias with SCDs as

a cause of splenomegaly, and tissue ischemia

and infarctions induced edematous splenomegaly

in early lives of the SCDs cases, splenomegaly

induced flow disorders of left renal vein

may be the most significant cause among

them.

Key words:

Sickle cell diseases, splenomegaly, left

renal vein, left renal atrophy

|

Arterio- or atherosclerosis, but not venosclerosis,

is an inflammatory process, probably developing

secondary to the much higher arterial pressure

induced chronic endothelial damage all over

the body. It may be the main cause of aging

induced end-organ failures in human beings (1,2).

It is a systemic and irreversible process initiating

at birth, and accelerated by many factors. The

accelerating factors known for the moment are

collected under the heading of metabolic syndrome.

Some reversible components of the syndrome are

overweight, hypertriglyceridemia, hyperbetalipoproteinemia,

dyslipidemia, white coat hypertension, impaired

fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance,

and smoking for the development of terminal

consequences such as obesity, diabetes mellitus

(DM), hypertension (HT), coronary heart disease

(CHD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

(COPD), cirrhosis, chronic renal disease (CRD),

peripheric artery disease (PAD), stroke, and

other end-organ failures (3-8). Sickle cell

diseases (SCDs) are a prototype of the accelerated

atherosclerosis (9,10), by which we can observe

terminal consequences of the metabolic syndrome

very early in life. SCDs are caused by homozygous

inheritance of the hemoglobin S (Hb S). Hb S

causes erythrocytes to change their normal elastic

structures to hard bodies. Actually, rigidity

instead of shapes of the erythrocytes is the

central pathology of the SCDs. The rigidity

process is probably present in whole life, but

exaggerated with stresses. The erythrocytes

can take their normal elastic structures after

normalization of the stresses, but after repeated

attacks of rigidity, they become hard bodies,

permanently. The rigid cells induced chronic

endothelial damage causes tissue ischemia, infarctions,

and end-organ failures even in the absence of

obvious vascular occlusions due to the damaged

and edematous endothelium. We tried to understand

whether or not there is a difference according

to the renal atrophy between the left and right

sides in the SCDs patients.

The study was performed in the Hematology

Service of the Mustafa Kemal University between

March 2007 and May 2013. All patients with SCDs

were enrolled into the study. SCDs are diagnosed

by the hemoglobin electrophoresis performed

via high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

method. Their medical histories including smoking

habit, regular alcohol consumption, leg ulcers,

and stroke were learnt. Cases with a history

of three pack-year were accepted as smokers

and cases with a history of regular alcohol

consumption with one drink a day for three years

were accepted as alcoholics. A check up procedure

including serum iron, total iron binding capacity,

serum ferritin, serum creatinine value on three

occasions, hepatic function tests, markers of

hepatitis viruses A, B, and C and human immunodeficiency

virus, an electrocardiogram, a Doppler echocardiogram,

an abdominal ultrasonography, and a computed

tomography of the brain were performed. Cases

with acute painful crisis or any other inflammatory

event were treated at first, and then the spirometric

pulmonary function tests to diagnose COPD, the

Doppler echocardiography to measure the systolic

pressure of pulmonary artery, renal and hepatic

function tests, and measurement of serum ferritin

level were performed on the silent phase. Renal

atrophies were detected ultrasonographically.

The criterion for diagnosis of COPD is post-bronchodilator

forced expiratory volume in 1 second/forced

vital capacity of less than 70% (11). Systolic

pressure of the pulmonary artery of 40 mmHg

or higher during the silent phase is accepted

as pulmonary hypertension (12). CRD is diagnosed

with a permanently elevated serum creatinine

level of 1.3 mg/dL or higher on the silent phase.

Cases with renal transplantation were put into

the CRD group. Cirrhosis is diagnosed with hepatic

function tests, ultrasonographic findings, ascites,

and histologic procedure in case of requirement.

Digital clubbing is diagnosed with the ratio

of distal phalangeal diameter to interphalangeal

diameter of higher than 1.0 and with the presence

of Schamroth's sign (13,14). Associated thalassemias

are diagnosed by serum iron, total iron binding

capacity, serum ferritin, and the hemoglobin

electrophoresis performed via HPLC method. A

stress electrocardiography was performed in

cases with an abnormal electrocardiogram and/or

angina pectoris. A coronary angiography was

obtained just for the stress electrocardiography

positive cases. So CHD was diagnosed either

with the Doppler echocardiographic findings

as the movement disorders of the cardiac walls

or angiographically. Mann-Whitney U test, Independent-Samples

t test, and comparison of proportions were used

as the methods of statistical analyses.

The

study

included

311

patients

with

the

SCDs

(153

females

and

158

males).

The

mean

ages

of

them

were

28.2

±

9.2

(8-59)

versus

29.9

±

9.6

(6-58)

years

in

females

and

males,

respectively

(p>0.05).

Interestingly,

there

were

seven

cases

(2.2%)

of

the

left

renal

atrophy

against

only

one

case

(0.3%)

of

the

right

renal

atrophy

(p<0.001)

among

the

study

cases

(Table

1).

On

the

other

hand,

associated

thalassemias

were

detected

in

44.0%,

splenomegaly

in

12.5%,

and

autosplenectomy

in

48.5%

of

the

SCDs

patients.

Although

smoking

was

observed

in

7.0%

of

the

patients,

there

was

only

one

case

(0.3%)

with

regular

alcohol

consumption.

Additionally,

there

were

digital

clubbing

in

6.4%,

COPD

in

4.8%,

leg

ulcers

in

12.8%,

stroke

in

7.0%,

CRD

in

8.6%,

pulmonary

hypertension

in

11.8%,

cirrhosis

in

3.5%,

CHD

in

8.0%,

and

exitus

in

5.7%

of

the

cases

with

the

SCDs.

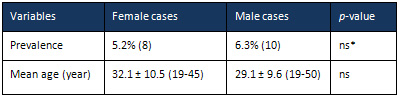

Prevalence

of

mortality

were

similar

in

both

genders

(5.2%

versus

6.3%

in

females

and

males,

respectively,

p>0.05),

and

mean

ages

of

the

mortal

cases

were

32.1

versus

29.1

years

in

females

and

males,

respectively

(p>0.05)

(Table

2).

On

the

other

hand,

five

of

the

CRD

cases

were

on

hemodialysis,

and

one

with

right

renal

transplantation.

Histologic

procedure

for

the

diagnosis

of

cirrhosis

was

not

required

in

any

case.

Although

antiHCV

was

positive

in

two

of

the

cirrhotics,

HCV

RNA

was

detected

as

negative

by

polymerase

chain

reaction

in

both.

The

solitary

case

of

regular

alcohol

consumption

was

not

cirrhotic

at

the

time

of

study.

Table

1:

Sickle

cell

patients

with

associated

disorders

Table

2:

Features

of

the

mortal

cases

Nephrons

are

the

basic

functional

units

of

the

kidneys

located

in

the

renal

parenchyma,

and

each

kidney

contains

about

one

million

nephrons.

Renal

atrophy

is

characterized

by

shrinkage

of

kidneys

due

to

loss

of

nephrons.

Loss

of

nephrons

also

causes

shrinkages

of

the

renal

arteries

and

veins,

secondarily.

Renal

diseases,

urinary

tract

obstructions,

or

acute

or

chronic

pyelonephritis

may

cause

renal

atrophy.

Reflux

nephropathy

is

characterized

by

renal

damage

due

to

the

backflow

of

urine,

and

it

may

also

cause

renal

atrophy.

Renal

atrophy

may

also

be

caused

by

the

obstruction

of

urinary

tract

due

to

an

increased

pressure

on

it,

or

compression

of

the

intrarenal

veins

or

arteries.

Obstructive

uropathy

causes

a

higher

urinary

pressure

within

the

kidneys

causing

damage

to

the

nephrons.

Although

the

various

etiologies,

probably

renal

ischemia

is

the

most

frequent

cause

of

the

renal

atrophy.

Probably

the

most

common

cause

of

renal

ischemia

is

the

systemic

atherosclerosis,

and

CRD

due

to

the

systemic

atherosclerosis

is

common

in

elderlies.

Although

the

younger

mean

ages,

we

detected

CRD

in

8.6%

of

all

cases

in

the

present

study,

since

the

SCDs

are

an

accelerated

systemic

atherosclerotic

process.

SCDs

are

accelerated

systemic

atherosclerotic

processes

(9)

initiating

at

birth,

and

by

which

we

can

observe

final

consequences

of

the

systemic

atherosclerosis

which

began

30

or

40

years

earlier

in

life.

Actually

name

of

the

syndrome

should

be

'Rigid

Cell

Induced

Chronic

Endothelial

Dysfunction'

instead

of

the

SCDs

or

sickle

cell

anemia

since

we

cannot

observe

the

sickle

cells

in

the

peripheric

blood

samples

of

cases

with

additional

thalassemias,

easily.

On

the

other

hand,

the

rigidity

of

the

erythrocytes

is

the

main

problem

instead

of

their

shapes

or

severity

of

anemia.

The

rigid

cells

induced

chronic

endothelial

damage

causes

tissue

ischemia,

infarction,

and

end-organ

failures

even

in

the

absence

of

obvious

vascular

occlusions

on

the

chronic

background

of

damaged

and

edematous

endothelium

all

over

the

body.

Even

there

were

patients

with

severe

vision

or

hearing

loss

among

the

present

study

cases.

The

digital

clubbing

and

recurrent

leg

ulcers

may

also

indicate

the

chronic

tissue

hypoxia

in

such

patients.

Due

to

the

reversibility

of

digital

clubbing

and

leg

ulcers

with

the

hydroxyurea

treatment,

the

chronic

endothelial

damage

is

probably

prominent

at

the

microvascular

level

as

in

diabetic

microangiopathies,

and

reversible

to

some

extent.

Although

large

arteries

and

arterioles

are

especially

important

for

blood

carriage,

capillaries

are

more

important

for

tissue

oxygenation.

So

passage

of

the

rigid

cells

through

the

endothelial

cells

cause

damage

on

the

capillaries.

Reversibility

of

the

process

may

probably

be

more

in

early

years

of

life

but

it

gets

an

irreversible

nature

over

time.

Thus

endothelial

cells

all

over

the

body

are

edematous

and

swollen

due

to

the

destructive

process

as

in

splenomegaly

seen

in

early

years

of

life.

But

the

ischemic

process

terminates

with

tissue

fibrosis

and

shrinkage

all

over

the

body

as

in

autosplenectomy.

Even

there

were

four

cases

with

total

teeth

loss

and

one

case

with

right

ovarian

atrophy

among

the

study

cases.

The

solitary

case

of

right

renal

atrophy

may

also

be

explained

by

the

mechanism.

On

the

other

hand,

anemia

probably

is

not

the

cause

of

the

end-organ

failures

in

the

SCDs,

since

we

cannot

observe

any

shortened

survival

in

the

thalassemia

minor

cases

although

the

presence

of

a

moderate

anemia.

Although

the

mean

survivals

were

42

and

48

years

for

males

and

females

for

the

SCDs

in

the

literature

(15),

they

were

29.1

and

32.1

years

in

males

and

females

in

the

present

study,

respectively.

The

great

differences

between

the

survival

may

be

secondary

to

the

initiation

of

hydroxyurea

in

infancy

in

such

countries

(16).

The

accelerated

atherosclerotic

process

can

also

affect

the

renal

arteries,

and

may

lead

to

poor

perfusion

of

the

kidneys

leading

to

reduced

renal

function

and

failure.

The

right

renal

artery

is

longer

than

the

left

because

of

the

location

of

the

aorta,

since

the

aorta

is

found

on

the

left

side

of

the

body.

Additionally,

the

right

renal

artery

is

lower

than

the

left

because

of

the

lower

position

of

the

right

kidney.

So

the

left

kidney

possibly

has

a

relatively

higher

arterial

pressure

due

to

the

shorter

distance

to

heart

as

an

underlying

cause

of

endothelial

damage

induced

atherosclerosis.

But

according

to

our

opinion,

the

accelerated

atherosclerotic

process

alone

cannot

explain

the

significantly

higher

prevalence

of

renal

atrophy

on

the

left

side

(2.2%

versus

0.3%,

p<0.001)

in

the

present

study.

The

left

renal

atrophy

has

also

been

reported

in

the

literature

(17).

On

the

other

hand,

the

very

high

prevalences

of

associated

thalassemias

(44.0%)

and

splenomegaly

(12.5%)

with

the

SCDs

cases

may

be

important

for

the

explanation,

since

spleen

and

left

kidney

are

closely

related

organs

which

may

also

be

observed

with

the

development

of

varicose

veins

from

the

left

renal

vein

at

the

splenic

hilus

in

cirrhotic

cases.

Any

pressure

on

the

left

kidney

as

in

splenomegaly

cases

may

cause

torsion

of

the

renal

vein,

and

prevents

its

drainage.

We

especially

think

about

the

drainage

problems

at

the

venous

level

due

to

the

much

higher

arterial

pressure

that

cannot

be

obstructed

easily

and

the

much

higher

prevalence

of

varicocele

in

the

left

side

in

males

(18-20).

Varicocele

is

a

dilatation

of

pampiniform

venous

plexus

within

the

scrotum.

It

occurs

in

15-20%

of

all

males

and

40%

of

infertile

males,

since

researchers

documented

a

recurrent

pattern

of

low

sperm

count,

poor

motility,

and

predominance

of

abnormal

sperm

forms

in

varicocele

cases

(21,22).

Varicoceles

are

much

more

common

(nearly

80%

to

90%)

in

the

left

side

due

to

several

anatomic

factors

including

angle

at

which

the

left

testicular

vein

enters

the

left

renal

vein,

lack

of

effective

antireflux

valves

at

the

juncture

of

left

testicular

vein

and

left

renal

vein,

the

nutcracker

syndrome,

and

some

other

left

renal

vein

anomalies

such

as

passage

behind

the

aorta.

The

nutcracker

syndrome

results

mostly

from

the

compression

of

the

left

renal

vein

between

the

abdominal

aorta

and

superior

mesenteric

artery,

although

other

variants

exist

(23).

It

may

cause

hematuria

and

left

flank

pain

(24).

Since

the

left

gonad

drains

via

the

left

renal

vein,

it

can

also

result

in

left

testicular

pain

in

men

or

left

lower

quadrant

pain

in

women

(25).

Nausea

and

vomiting

may

result

due

to

compression

of

the

splanchnic

veins

(25).

An

unusual

manifestation

of

the

nutcracker

syndrome

includes

varicocele

formation

and

varicose

veins

in

the

lower

limbs

(26).

Another

study

has

shown

that

the

nutcracker

syndrome

is

a

frequent

finding

in

varicocele

patients

(27),

so

it

should

be

routinely

searched

in

cases

with

left

varicocele.

As

a

conclusion,

the

renal

atrophy

is

significantly

higher

on

the

left

side

in

the

SCDs

cases.

Splenomegaly

induced

flow

disorders

in

the

left

renal

vessels,

structural

anomalies

of

the

left

renal

vein

including

nutcracker

syndrome

and

passage

behind

the

aorta,

and

possibly

the

higher

arterial

pressure

of

the

left

kidney

due

to

the

shorter

distance

to

heart

as

an

underlying

cause

of

endothelial

damage

induced

atherosclerosis

may

be

some

of

the

possible

causes.

Because

of

the

higher

prevalences

of

left

varicocele

probably

due

to

drainage

of

left

testicular

vein

into

the

left

renal

vein,

high

prevalences

of

associated

thalassemias

with

the

SCDs

as

a

cause

of

splenomegaly,

and

tissue

ischemia

and

infarctions

induced

edematous

splenomegaly

in

early

lives

of

the

SCDs

cases,

splenomegaly

induced

flow

disorders

of

the

left

renal

vein

may

be

the

most

significant

cause

among

them.

1.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydin

LY,

Aydin

Y.

Digital

clubbing

may

be

an

indicator

of

systemic

atherosclerosis

even

at

microvascular

level.

HealthMED

2012;

6:

3977-3981.

2.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydin

Y,

Gundogdu

M.

Smoking

induced

atherosclerosis

in

cancers.

HealthMED

2012;

6:

3744-3749.

3.

Eckel

RH,

Grundy

SM,

Zimmet

PZ.

The

metabolic

syndrome.

Lancet

2005;

365:

1415-1428.

4.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Gundogdu

M.

Association

of

increased

triglyceride

levels

in

metabolic

syndrome

with

coronary

artery

disease.

Pak

J

Med

Sci

2010;

26:

667-672.

5.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Seyhanli

M,

Yalcin

A.

White

coat

hypertension

in

definition

of

metabolic

syndrome.

Int

Heart

J

2008;

49:

449-457.

6.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Seyhanli

M,

Cosar

E.

White

coat

hypertension

is

associated

with

a

greater

all-cause

mortality.

J

Health

Sci

2007;

53:

156-160.

7.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Duru

M,

Yalcin

A.

What

is

the

relationship

between

white

coat

hypertension

and

dyslipidemia?

Int

Heart

J

2008;

49:

87-93.

8.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Sevinc

A,

Camci

C.

Body

weight

and

white

coat

hypertension.

Pak

J

Med

Sci

2009;

25:

916-921.

9.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydogan

F,

Sevinc

A,

Camci

C,

Dilek

I.

Platelet

and

white

blood

cell

counts

in

severity

of

sickle

cell

diseases.

Pren

Med

Argent

2014;

100:

49-56.

10.

Helvaci

MR,

Sevinc

A,

Camci

C,

Keskin

A.

Atherosclerotic

background

of

cirrhosis

in

sickle

cell

patients.

Pren

Med

Argent

2014;

100:

127-133.

11.

Global

strategy

for

the

diagnosis,

management

and

prevention

of

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease

2010.

Global

initiative

for

chronic

obstructive

lung

disease

(GOLD).

12.

Fisher

MR,

Forfia

PR,

Chamera

E,

Housten-Harris

T,

Champion

HC,

Girgis

RE,

et

al.

Accuracy

of

Doppler

echocardiography

in

the

hemodynamic

assessment

of

pulmonary

hypertension.

Am

J

Respir

Crit

Care

Med

2009;

179:

615-621.

13.

Schamroth

L.

Personal

experience.

S

Afr

Med

J

1976;

50:

297-300.

14.

Vandemergel

X,

Renneboog

B.

Prevalence,

aetiologies

and

significance

of

clubbing

in

a

department

of

general

internal

medicine.

Eur

J

Intern

Med

2008;

19:

325-329.

15.

Platt

OS,

Brambilla

DJ,

Rosse

WF,

Milner

PF,

Castro

O,

Steinberg

MH,

et

al.

Mortality

in

sickle

cell

disease.

Life

expectancy

and

risk

factors

for

early

death.

N

Engl

J

Med

1994;

330:

1639-1644.

16.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydin

Y,

Ayyildiz

O.

Hydroxyurea

may

prolong

survival

of

sickle

cell

patients

by

decreasing

frequency

of

painful

crises.

HealthMED

2013;

7:

2327-2332.

17.

Ekim

M,

Tumer

N,

Yalcinkaya

F,

Cakar

N.

Unilateral

renal

atrophy

and

hypertension

(imaging

techniques

in

children

with

hyperreninaemic

hypertension)

(a

case

report).

Int

Urol

Nephrol

1995;

27:

375-379.

18.

Simmons

MZ,

Wachsberg

RH,

Levine

CD,

Spiegel

N.

Intra-testicular

varicocele:

gray-scale

and

Doppler

ultrasound

findings.

J

Clin

Ultrasound

1996;

24:

371-374.

19.

Ozcan

H,

Aytac

S,

Yagci

C,

Turkolmez

K,

Kosar

A,

Erden

I.

Color

Doppler

ultrasonographic

findings

in

intratesticular

varicocele.

J

Clin

Ultrasound

1997;

25:

325-329.

20.

Mehta

AL,

Dogra

VS.

Intratesticular

varicocele.

J

Clin

Ultrasound

1998;

26:

49-51.

21.

O'Donnell

PG,

Dewbury

KC.

The

ultrasound

appearances

of

intratesticular

varicocele.

Br

J

Radiol

1998;

71:

324-325.

22.

Das

KM,

Prasad

K,

Szmigielski

W,

Noorani

N.

Intratesticular

varicocele:

evaluation

using

conventional

and

Doppler

sonography.

AJR

Am

J

Roentgenol

1999;

173:

1079-1083.

23.

Kurklinsky

AK,

Rooke

TW.

Nutcracker

phenomenon

and

nutcracker

syndrome.

Mayo

Clin

Proc

2010;

85:

552-559.

24.

Oteki

T,

Nagase

S,

Hirayama

A,

Sugimoto

H,

Hirayama

K,

Hattori

K,

et

al.

Nutcracker

syndrome

associated

with

severe

anemia

and

mild

proteinuria.

Clin

Nephrol

2004;

62:

62-65.

25.

Hilgard

P,

Oberholzer

K,

Meyer

zum

Büschenfelde

KH,

Hohenfellner

R,

Gerken

G.

The

"nutcracker

syndrome"

of

the

renal

vein

(superior

mesenteric

artery

syndrome)

as

the

cause

of

gastrointestinal

complaints.

Dtsch

Med

Wochenschr

1998;

123:

936-940.

26.

Little

AF,

Lavoipierre

AM.

Unusual

clinical

manifestations

of

the

Nutcracker

Syndrome.

Australas

Radiol

2002;

46:

197-200.

27.

Mohammadi

A,

Ghasemi-Rad

M,

Mladkova

N,

Masudi

S.

Varicocele

and

nutcracker

syndrome:

sonographic

findings.

J

Ultrasound

Med

2010;

29:

1153-1160.

|