|

Red blood cell supports

in severe clinical conditions in sickle cell

diseases

Mehmet Rami

Helvaci (1)

Nesrin Atci (2)

Orhan Ayyildiz (3)

Orhan Ekrem Muftuoglu (3)

Lesley Pocock (4)

(1) Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

Antakya, Professor of Internal Medicine, M.D.

(2) Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

Antakya, Assistant Professor of Radiology, M.D.

(3) Medical Faculty of the Dicle University,

Diyarbakir, Professor of Internal Medicine,

M.D.

(4) Lesley Pocock, Publisher, medi+WORLD International

Correspondence:

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, M.D.

Medical Faculty of the Mustafa Kemal University,

31100, Serinyol, Antakya, Hatay, TURKEY

Phone: 00-90-326-2291000 (Internal 3399) Fax:

00-90-326-2455654

Email: mramihelvaci@hotmail.com

|

Abstract

Background:

Sickle cell diseases (SCDs) are accelerated

atherosclerotic processes. We tried to

understand whether or not there is a prolonged

survival with the increased number of

red blood cells (RBC) transfusion in the

SCDs.

Methods: As one of the significant

endpoints of the SCDs, cases with chronic

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and

without, were collected into the two groups.

Results: The

study included 428 patients (221 males).

There were 71 patients (16.5%) with COPD.

Mean age was significantly higher in the

COPD group (32.8 versus 29.8 years, P=0.005).

Male ratio was significantly higher in

the COPD group, too (78.8% versus 46.2%,

P<0.001). Smoking (35.2% versus 11.4%,

P<0.001) and alcohol (7.0% versus 1.9%,

P<0.01) were also higher among the

COPD cases. Beside these, priapism (14.0%

versus 3.0%, P<0.001), HCV RNA positivity

(2.7% versus 0.5%, P<0.05), cirrhosis

(8.4% versus 3.3%, P<0.05), leg ulcers

(23.9% versus 12.0%, P<0.01), digital

clubbing (25.3% versus 6.7%, P<0.001),

coronary heart disease (23.9% versus 13.7%,

P<0.05), chronic renal disease (15.4%

versus 7.0%, P<0.01), stroke (16.9%

versus 8.1%, P<0.01), and mean transfused

RBC units in their lives (63.8 versus

33.0, P=0.003) were all higher among the

COPD cases. This was probably due to the

higher number of transfused RBC units;

the mean age of mortality was also higher

in the COPD group, significantly (38.3

versus 30.4 years, P=0.04).

Conclusion:

SCDs are chronic catastrophic processes

on vascular endothelium terminating with

accelerated atherosclerosis induced end-organ

failures in early years of life. RBC supports

in severe clinical conditions probably

prolong survival of the patients.

Key words: Sickle

cell diseases, chronic endothelial damage,

red blood cell support

|

Chronic endothelial damage may be the major

cause of aging and mortality by inducing disseminated

cellular hypoxia all over the body. Much higher

blood pressure (BP) of the afferent vasculature

may be the major underlying cause, and probably

whole afferent vasculature including capillaries

are mainly involved in the process. Some of

the well-known accelerators of the inflammatory

process are physical inactivity, weight gain,

smoking, and alcohol for the development of

irreversible endpoints including obesity, hypertension,

diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, peripheric artery

disease (PAD), chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease (COPD), chronic renal disease (CRD),

coronary heart disease (CHD), mesenteric ischemia,

osteoporosis, teeth loss, and stroke, all of

which terminate with early aging and mortality.

They were researched under the title of metabolic

syndrome in the literature, extensively (1,

2). Similarly, sickle cell diseases (SCDs) are

chronic catastrophic processes on vascular endothelium

particularly at the capillary level, and terminate

with accelerated atherosclerosis induced end-organ

failures in early years of life. Hemoglobin

S (HbS) causes loss of elastic and biconcave

disc shaped structures of red blood cells (RBCs).

Probably loss of elasticity instead of shape

is the main problem because sickling is rare

in peripheric blood samples of patients with

associated thalassemia minors, and human survival

is not so affected in hereditary spherocytosis

or elliptocytosis. Loss of elasticity is present

in whole lifespan, but exaggerated with increased

metabolic rate of the body. The hard RBCs induced

prolonged endothelial inflammation, edema, and

fibrosis mainly at the capillary level terminate

with cellular hypoxia all over the body (3-5).

Capillary vessels are mainly involved in the

process due to their distribution function for

the hard RBCs. We tried to understand whether

or not there is a prolonged survival with the

increased number of RBC supports in the SCDs

in the present study.

The study was performed in Medical Faculty

of the Mustafa Kemal University between March

2007 and February 2016. All patients with the

SCDs were studied. The SCDs are diagnosed with

the hemoglobin electrophoresis performed via

high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Medical histories including smoking habit, regular

alcohol consumption, painful crises per year,

transfused RBC units in their lives, surgical

operations, priapism, leg ulcers, and stroke

were learnt. Patients with a history of one

pack-year were accepted as smokers, and one

drink-year were accepted as drinkers. A complete

physical examination was performed by the same

internist. Cases with prominent teeth loss (8

or more) were detected. Cases with acute painful

crisis or another inflammatory event were treated

at first, and the laboratory tests and clinical

measurements were performed on the silent phase.

A check up procedure including serum iron, iron

binding capacity, ferritin, creatinine, liver

function tests, markers of hepatitis viruses

A, B, and C and human immunodeficiency virus,

a posterior-anterior chest x-ray film, an electrocardiogram,

a Doppler echocardiogram both to evaluate cardiac

walls and valves and to measure systolic BP

of pulmonary artery, an abdominal ultrasonography,

a venous Doppler ultrasonography of the lower

limbs, a computed tomography of brain, and a

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of hips were

performed. Other bones for avascular necrosis

were scanned according to the patients' complaints.

Associated thalassemia minors were detected

with serum iron, iron binding capacity, ferritin,

and hemoglobin electrophoresis performed via

HPLC. The criterion for diagnosis of COPD is

post-bronchodilator forced expiratory volume

in one second/forced vital capacity of less

than 70% (6). Acute chest syndrome (ACS) is

diagnosed clinically with the presence of new

infiltrates on chest x-ray film, fever, cough,

sputum production, dyspnea, or hypoxia (7).

An x-ray film of abdomen in upright position

was taken just in patients with abdominal distention

or discomfort, vomiting, obstipation, or lack

of bowel movement, and ileus was diagnosed with

gaseous distention of isolated segments of bowel,

vomiting, obstipation, cramps, and with the

absence of peristaltic activity on the abdomen.

Systolic BP of the pulmonary artery of 40 mmHg

or higher is accepted as pulmonary hypertension

(8). CRD is diagnosed with a persistent serum

creatinine level of 1.3 mg/dL in males and 1.2

mg/dL in females. Cirrhosis is diagnosed with

physical examination, hepatic function tests,

ultrasonographic results, and tissue sample

in case of indication. Digital clubbing is diagnosed

with the ratio of distal phalangeal diameter

to interphalangeal diameter which is greater

than 1.0, and with the presence of Schamroth's

sign (9, 10). An exercise electrocardiogram

is just performed in cases with an abnormal

electrocardiogram and/or angina pectoris. Coronary

angiography is taken just for the exercise electrocardiogram

positive cases. So CHD was diagnosed either

angiographically or with the Doppler echocardiographic

findings as the movement disorders in the cardiac

walls. Rheumatic heart disease is diagnosed

with the echocardiographic findings, too. Avascular

necrosis of bones is diagnosed by means of MRI

(11). Stroke is diagnosed by the computed tomography

of brain. Ophthalmologic examination was performed

according to the patients' complaints. Eventually

as one of the significant endpoints of the SCDs,

cases with COPD and without were collected into

the two groups, and they were compared in between.

Mann-Whitney U test, Independent-Samples t test,

and comparison of proportions were used as the

methods of statistical analyses.

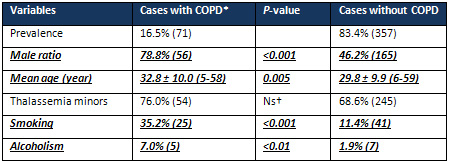

The

study

included

428

patients

with

the

SCDs

(207

females

and

221

males)

during

the

nine-year

follow-up

period.

There

were

71

patients

(16.5%)

with

COPD.

Mean

age

of

the

patients

was

significantly

higher

in

the

COPD

group

(32.8

versus

29.8

years,

P=0.005).

The

male

ratio

was

significantly

higher

in

the

COPD

group,

too

(78.8%

versus

46.2%,

P<0.001).

Smoking

(35.2%

versus

11.4%,

P<0.001)

and

alcohol

consumption

(7.0%

versus

1.9%,

P<0.01)

were

also

higher

among

the

COPD

cases.

Prevalences

of

associated

thalassemia

minors

were

similar

in

both

groups

(76.0%

versus

68.6%

in

the

COPD

group

and

other,

respectively,

P>0.05)

(Table

1).

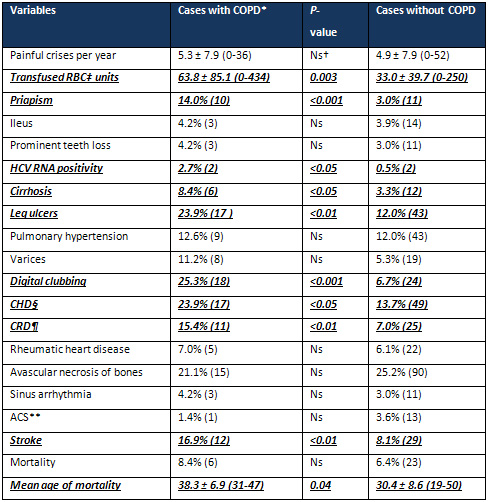

Beside

these,

priapism

(14.0%

versus

3.0%,

P<0.001),

cirrhosis

(8.4%

versus

3.3%,

P<0.05),

leg

ulcers

(23.9%

versus

12.0%,

P<0.01),

digital

clubbing

(25.3%

versus

6.7%,

P<0.001),

CHD

(23.9%

versus

13.7%,

P<0.05),

CRD

(15.4%

versus

7.0%,

P<0.01),

and

stroke

(16.9%

versus

8.1%,

P<0.01)

were

all

higher

in

the

COPD

group.

Additionally,

painful

crises

per

year

(5.3

versus

4.9),

ileus

(4.2%

versus

3.9%),

prominent

teeth

loss

(4.2%

versus

3.0%),

pulmonary

hypertension

(12.6%

versus

12.0%),

varices

(11.2%

versus

5.3%),

rheumatic

heart

disease

(7.0%

versus

6.1%),

sinus

arrhythmia

(4.2%

versus

3.0%),

and

mortality

(8.4%

versus

6.4%)

were

all

higher

among

the

COPD

cases,

too

but

the

differences

were

nonsignificant

probably

due

to

the

small

sample

size

of

the

COPD

group.

Parallel

to

the

above

consequences,

mean

transfused

RBC

units

in

their

lives

were

significantly

higher

among

the

COPD

cases

(63.8

versus

33.0,

P=0.003).

Probably

due

to

the

higher

number

of

transfused

RBC

units

in

their

lives,

the

mean

age

of

mortality

was

significantly

higher

in

the

COPD

group

(38.3

versus

30.4

years,

P=0.04)

(Table

2).

On

the

other

hand,

there

was

one

patient

(1.4%)

with

HBsAg

positivity

in

the

COPD

group

and

4

patients

(1.1%)

among

the

others

(P>0.05),

but

HBV

DNA

was

positive

in

none

of

them

by

polymerase

chain

reaction

(PCR)

method.

Although

antiHCV

positivity

was

similar

in

both

groups

(4.2%

versus

6.1%

of

the

COPD

patients

and

others,

respectively,

P>0.05),

HCV

RNA

positivity

was

significantly

higher

in

the

COPD

group

(2.7%

versus

0.5%

of

the

COPD

group

and

other,

respectively,

P<0.05)

by

PCR.

On

the

other

hand,

there

were

three

patients

with

the

sickle

cell

retinopathy

in

the

group

without

COPD.

Table

1:

Characteristic

features

of

the

study

cases

*Chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease

†Nonsignificant

(P>0.05)

Table

2:

Associated

pathologies

of

the

study

cases

*Chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease

†Nonsignificant

(P>0.05)

‡Red

blood

cell

§Coronary

heart

disease

Chronic

renal

disease

**Acute

chest

syndrome

*Chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease

†Nonsignificant

(P>0.05)

‡Red

blood

cell

§Coronary

heart

disease

Chronic

renal

disease

**Acute

chest

syndrome

Chronic

endothelial

damage

may

be

the

most

common

type

of

vasculitis,

and

the

leading

cause

of

aging

and

mortality

in

human

beings.

Physical

inactivity,

weight

gain,

smoking,

alcohol,

prolonged

infections,

and

chronic

inflammatory

processes

including

SCDs,

rheumatologic

disorders,

and

cancers

may

accelerate

the

process.

Probably

whole

afferent

vasculature

including

capillaries

are

mainly

involved

in

the

process.

Much

higher

BP

of

the

afferent

vasculature

may

be

the

major

underlying

cause

by

inducing

recurrent

micro-injuries

on

endothelium.

Thus

the

term

of

venosclerosis

is

not

as

famous

as

arteriosclerosis

or

atherosclerosis

in

the

literature.

Secondary

to

the

chronic

endothelial

inflammation,

edema,

and

fibrosis,

vascular

walls

become

thickened,

their

lumens

are

narrowed,

and

they

lose

their

elastic

nature

that

reduces

blood

flow

and

increases

BP

further.

Although

early

withdrawal

of

causative

factors

may

delay

final

consequences,

after

development

of

cirrhosis,

COPD,

CRD,

CHD,

PAD,

or

stroke,

endothelial

changes

cannot

be

reversed

completely

due

to

the

fibrotic

nature

of

them

(12).

SCDs

are

life-threatening

hereditary

disorders

nearly

affecting

100,000

individuals

in

the

United

States

(13).

As

a

difference

from

other

causes

of

chronic

endothelial

damage,

they

probably

keep

vascular

endothelium

particularly

at

the

capillary

level

(14),

since

the

capillary

system

is

the

main

distributor

of

the

hard

RBCs

to

the

tissues.

The

hard

cells

induced

chronic

endothelial

damage,

inflammation,

edema,

and

fibrosis

build

up

an

advanced

atherosclerosis

in

younger

ages

of

the

patients.

As

a

result,

mean

lifespans

of

the

patients

were

48

years

in

females

and

42

years

in

males

in

the

literature

(15),

whereas

they

were

33.6

and

30.8

years

in

the

present

study,

respectively.

The

great

differences

may

be

due

to

delayed

diagnosis

of

the

diseases,

delayed

initiation

of

hydroxyurea

therapy,

and

inadequate

RBC

supports

in

severe

clinical

conditions

in

our

country.

Actually,

RBC

supports

must

be

given

whenever

there

is

evidence

of

clinical

deterioration

in

the

patients

(16,

17).

RBC

supports

decrease

sickle

cell

concentration

in

circulation

and

suppress

bone

marrow

about

the

production

of

abnormal

RBCs.

So

they

decrease

sickling

induced

endothelial

damage

of

organs

in

crises.

According

to

our

nine-year

experience,

simple

and

repeated

transfusions

are

superior

to

RBC

exchange.

First

of

all,

preparation

of

one

or

two

units

of

RBC

suspensions

each

time

rather

than

preparation

of

six

units

or

higher

provides

time

for

clinicians

to

prepare

more

units

by

preventing

sudden

death

of

such

patients.

Secondly,

transfusions

of

one

or

two

units

of

RBC

suspensions

each

time

decreases

the

severity

of

pain

and

relaxes

anxiety

of

the

patients

and

surroundings

in

a

short

period

of

time.

Thirdly,

transfusions

of

lesser

units

of

RBC

suspensions

each

time

by

means

of

simple

transfusions

will

decrease

transfusion-related

complications

in

the

future.

Fourthly,

transfusion

of

RBC

suspensions

in

secondary

health

centers

may

prevent

some

deaths

developed

during

transport

to

tertiary

centers

for

the

exchange.

On

the

other

hand,

longer

lifespan

of

females

in

the

SCDs

(15)

and

longer

overall

survival

of

females

in

the

world

(18)

cannot

be

explained

by

the

atherosclerotic

effects

of

smoking

and

alcohol

alone,

instead

it

may

be

explained

by

physical

power

requiring

role

of

males

that

may

terminate

with

an

exaggerated

sickling

and

atherosclerosis

all

over

the

body

(19).

COPD

is

the

third

leading

cause

of

mortality

with

different

underlying

etiologies

in

the

world

(20).

It

is

an

inflammatory

disorder

mainly

affecting

the

pulmonary

vasculature,

and

smoking,

excess

weight,

and

aging

may

be

the

major

causes.

Regular

alcohol

consumption

may

also

take

place

in

the

inflammatory

process.

For

example,

the

prevalence

of

alcohol

consumption

was

significantly

higher

in

the

COPD

group

(7.0%

versus

1.9%,

P<0.01),

here.

Similarly,

COPD

was

one

of

the

most

frequent

associated

disorders

in

alcohol

dependence

in

another

study

(21).

Additionally,

30-day

readmission

rate

was

higher

in

COPD

patients

with

alcoholism

(22).

Probably

an

accelerated

atherosclerotic

process

is

the

main

structural

background

of

functional

changes

that

are

characteristics

of

COPD.

The

endothelial

process

is

enhanced

with

release

of

various

chemicals

by

inflammatory

cells,

and

terminates

with

endothelial

fibrosis

and

tissue

loss

in

lungs.

Although

COPD

may

mainly

be

an

accelerated

atherosclerotic

process

of

the

pulmonary

vasculature,

there

are

several

reports

about

coexistence

of

disseminated

endothelial

inflammation

all

over

the

body

(23,

24).

For

example,

close

relationships

were

shown

between

COPD,

CHD,

PAD,

and

stroke

(25).

Similarly,

two-thirds

of

mortality

cases

were

caused

by

cardiovascular

diseases

and

lung

cancers

in

smokers

in

a

multi-center

study

(26).

When

the

hospitalizations

were

researched,

the

most

common

causes

were

the

cardiovascular

diseases

again

(26).

In

another

study,

27%

of

all

mortality

was

due

to

the

cardiovascular

causes

in

the

moderate

and

severe

COPD

cases

(27).

Due

to

the

strong

atherosclerotic

natures

of

the

SCDs

and

COPD,

COPD

may

be

one

of

the

terminal

endpoints

of

the

SCDs

due

to

the

higher

prevalence

of

priapism,

cirrhosis,

leg

ulcers,

digital

clubbing,

CHD,

CRD,

and

stroke

in

the

COPD

group,

here.

Painful

crises

are

the

most

disabling

and

nearly

pathognomonic

symptoms

of

the

SCDs.

For

example,

only

11.9%

of

the

study

cases

(9.8%

versus

12.3%

in

the

COPD

and

other

groups,

respectively,

P>0.05)

have

not

had

any

painful

crisis

in

their

lives,

here.

Although

the

crises

may

not

be

life

threatening

directly

(28),

infections

are

the

most

common

precipitating

factors

of

them.

The

patients

are

immunocompromised

due

to

a

variety

of

reasons

including

a

functional

and

anatomic

asplenism,

chronic

endothelial

damage

induced

end-organ

failures,

a

permanent

inflammatory

process

all

over

the

body,

hospitalizations,

transfusions,

and

invasive

procedures.

Because

of

the

deep

immunodeficiency,

simple

infections

may

even

progress

to

sepsis

in

a

short

period

of

time.

Thus

multiorgan

failures

and

mortality

are

not

rare

during

acute

painful

crises

in

them.

Similarly,

RBC

supports

may

provide

adequate

tissue

oxygenation

and

immunity,

and

so

prevent

intractable

pain,

dissemination

of

infections

or

inflammations,

end-organ

failures,

and

mortality

during

surgical

operations,

major

depressions,

and

other

severe

clinical

conditions.

On

the

other

hand,

pain

is

the

result

of

a

yet

poorly

understood

interaction

between

the

hard

cells,

endothelial

cells,

white

blood

cells

(WBC),

and

platelets

(PLT).

The

adverse

effects

of

WBCs

and

PLTs

on

endothelium

are

of

particular

interest.

For

example,

leukocytosis

even

at

the

silent

period

was

an

independent

predictor

of

severity

of

the

SCDs

(29),

and

it

was

associated

with

an

increased

risk

of

stroke

(30).

On

the

other

hand,

leukocytosis

and

thrombocytosis

are

acute

phase

reactants

that

are

also

present

during

the

silent

periods

in

the

SCDs.

They

indicate

presence

of

a

permanent

inflammatory

process

initiating

at

birth.

The

continuous

inflammatory

process

alone

causes

an

additional

accelerated

atherosclerotic

process

and

a

relative

weight

loss

in

the

SCDs

(31).

Occlusions

of

vasculature

of

the

bone

marrow,

bone

infarctions,

releasing

of

inflammatory

mediators,

and

activation

of

afferent

nerves

may

take

a

role

in

the

pathophysiology

of

the

intractable

pains.

Because

of

the

severity

of

pain,

narcotic

analgesics

are

usually

required

to

control

them

(32),

but

according

to

our

practice,

RBC

supports

are

highly

effective

during

severe

crises

both

to

relieve

pain

and

to

prevent

sudden

deaths

secondary

to

the

multiorgan

failures

developed

on

chronic

inflammatory

background

of

the

SCDs.

Probably

parallel

to

severity

of

the

inflammatory

process,

an

asplenism

develops

with

decreased

antibody

production,

prevented

opsonization,

and

reticuloendothelial

dysfunction

due

to

the

repeated

infarctions

and

subsequent

fibrosis

in

early

years

of

life.

Similarly,

the

prevalence

of

autosplenectomy

was

51.6%

(221

cases)

among

the

patients

with

an

average

age

of

30.3

±

10.0

years

(range

5-59),

here.

Terminal

consequence

of

the

asplenism

is

an

increased

risk

of

infections,

particularly

due

to

Streptococcus

pneumoniae,

Haemophilus

influenzae,

and

Neisseria

meningitidis

like

encapsulated

bacteria.

Thus,

infections

particularly

the

pneumococcal

infections

are

common

in

early

childhood,

and

they

are

associated

with

a

high

mortality

rate.

The

causes

of

mortality

were

infections

in

56%

of

infants

in

a

previous

study

(29).

In

another

study,

the

peak

incidence

of

mortality

occured

between

1

to

3

years

of

age

in

children,

and

the

deaths

were

predominantly

caused

by

pneumococcal

sepsis

in

patients

less

than

20

years

of

age

(33).

According

to

our

nine-year

experiences

in

adults,

patients

even

who

appear

relatively

fit

are

susceptible

to

sepsis,

multiorgan

failures,

and

sudden

death

during

acute

painful

crises

due

to

the

deep

immunosuppression

in

them.

ACS

is

responsible

for

considerable

mortality,

particularly

during

the

childhood

in

the

SCDs

(34).

It

occurs

most

often

as

a

single

episode,

and

a

past

history

is

associated

with

an

early

mortality

(34).

Similarly,

all

of

14

cases

with

the

ACS

had

only

a

single

episode,

and

two

of

them

in

the

group

without

COPD

were

fatal

in

spite

of

rigorous

RBC,

ventilation,

and

antibiotic

supports

in

the

present

study.

The

remaining

12

patients

are

still

alive

without

a

recurrence

at

the

end

of

the

nine-year

follow-up

period.

ACS

is

the

most

common

between

the

ages

of

2

to

4

years,

and

its

incidence

decreases

with

age

(35).

Parallel

to

the

knowledge,

its

incidence

was

only

3.2%

among

the

patients

with

an

average

age

of

30.3

years,

here.

The

decreased

incidence

with

aging

may

be

due

to

a

high

mortality

during

the

first

episode

and/or

an

acquired

immunity

against

various

antigens

with

aging.

On

the

other

hand,

ACS

may

also

show

inborn

severity

of

the

SCDs.

For

example,

its

incidence

is

higher

in

severe

cases

such

as

cases

with

sickle

cell

anemia

(HbSS)

and

a

higher

WBC

count

(34,

35).

Probably,

ACS

is

a

complex

event,

and

the

terminology

of

'ACS'

does

not

indicate

a

definite

diagnosis

but

reflects

clinical

difficulty

of

defining

a

distinct

etiology

in

the

majority

of

such

episodes.

One

of

the

major

clinical

problems

lies

in

distinguishing

between

infection

and

infarction,

and

in

establishing

clinical

significance

of

fat

embolism.

For

example,

ACS

did

not

show

an

infectious

etiology

in

66%

of

episodes

in

the

above

studies

(34,

35).

Similarly,

12

of

27

episodes

of

ACS

had

evidence

of

fat

embolism

as

the

cause

in

another

study

(36).

But

according

to

our

experiences,

the

increased

metabolic

rate

during

severe

infections

may

terminate

with

the

ACS.

In

other

words,

ACS

may

be

characterized

by

the

hard

RBCs-induced

disseminated

endothelial

damage

and

fat

embolism

at

the

capillary

level.

A

preliminary

result

from

the

Multi-Institutional

Study

of

Hydroxyurea

in

the

SCDs

(37)

indicating

a

significant

reduction

of

ACS

episodes

with

hydroxyurea

suggests

that

a

substantial

number

of

episodes

are

secondary

to

the

endothelial

inflammation

and

edema

at

the

capillary

level.

Similarly,

we

strongly

recommend

hydroxyurea

therapy

for

all

patients

at

any

age

that

may

also

be

a

cause

of

the

low

incidence

of

ACS

among

our

follow-up

cases,

here.

Hydroxyurea

is

the

only

drug

that

was

approved

by

Food

and

Drug

Administration

for

the

treatment

of

SCDs

(13).

It

is

an

oral,

cheap,

safe,

and

highly

effective

drug

for

the

SCDs

that

blocks

cell

division

by

suppressing

formation

of

deoxyribonucleotides

which

are

building

blocks

of

DNA

(13).

Its

main

action

may

be

suppression

of

hyperproliferative

WBCs

and

PLTs

in

the

SCDs

(14).

Although

presence

of

a

continuous

damage

of

hard

RBCs

on

capillary

endothelium,

severity

of

the

destructive

process

is

probably

exaggerated

by

the

patients'

own

WBCs

and

PLTs

as

in

the

autoimmune

disorders

(14).

Similarly,

lower

WBC

counts

were

associated

with

lower

crises

rates,

and

if

a

tissue

infarct

occurs,

lower

WBC

counts

may

decrease

severity

of

pain

and

tissue

damage

(38).

According

to

our

experiences,

hydroxyurea

is

an

effective

drug

for

prevention

or

delay

of

terminal

consequences

of

the

SCDs

if

it

is

initiated

in

early

years

of

life,

but

it

may

be

difficult

due

to

the

excessive

fibrosis

around

the

capillary

walls

in

nearly

all

organs

later

in

life.

As

a

conclusion,

SCDs

are

chronic

catastrophic

processes

on

vascular

endothelium

particularly

at

the

capillary

level,

and

terminate

with

accelerated

atherosclerosis

induced

end-organ

failures

in

early

years

of

life.

RBC

supports

in

severe

clinical

conditions

probably

prolong

the

survival

of

patients.

1.

Eckel

RH,

Grundy

SM,

Zimmet

PZ.

The

metabolic

syndrome.

Lancet

2005;

365:

1415-1428.

2.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H,

Sevinc

A,

Camci

C.

Body

weight

and

white

coat

hypertension.

Pak

J

Med

Sci

2009;

25:

6:

916-921.

3.

Helvaci

MR,

Gokce

C,

Davran

R,

Acipayam

C,

Akkucuk

S,

Ugur

M.

Tonsilectomy

in

sickle

cell

diseases.

Int

J

Clin

Exp

Med

2015;

8:

4586-4590.

4.

Helvaci

MR,

Gokce

C,

Davran

R,

Akkucuk

S,

Ugur

M,

Oruc

C.

Mortal

quintet

of

sickle

cell

diseases.

Int

J

Clin

Exp

Med

2015;

8:

11442-11448.

5.

Helvaci

MR,

Gokce

C,

Davarci

M,

Sahan

M,

Hakimoglu

S,

Coskun

M.

Chronic

endothelial

inflammation

and

priapism

in

sickle

cell

diseases.

Int

J

Clin

Exp

Med

2016;

(in

press).

6.

Global

strategy

for

the

diagnosis,

management

and

prevention

of

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease

2010.

Global

initiative

for

chronic

obstructive

lung

disease

(GOLD).

7.

Castro

O,

Brambilla

DJ,

Thorington

B,

Reindorf

CA,

Scott

RB,

Gillette

P,

et

al.

The

acute

chest

syndrome

in

sickle

cell

disease:

incidence

and

risk

factors.

The

Cooperative

Study

of

Sickle

Cell

Disease.

Blood

1994;

84:

643-649.

8.

Fisher

MR,

Forfia

PR,

Chamera

E,

Housten-Harris

T,

Champion

HC,

Girgis

RE,

et

al.

Accuracy

of

Doppler

echocardiography

in

the

hemodynamic

assessment

of

pulmonary

hypertension.

Am

J

Respir

Crit

Care

Med

2009;

179:

615-621.

9.

Vandemergel

X,

Renneboog

B.

Prevalence,

aetiologies

and

significance

of

clubbing

in

a

department

of

general

internal

medicine.

Eur

J

Intern

Med

2008;

19:

325-329.

10.

Schamroth

L.

Personal

experience.

S

Afr

Med

J

1976;

50:

297-300.

11.

Mankad

VN,

Williams

JP,

Harpen

MD,

Manci

E,

Longenecker

G,

Moore

RB,

et

al.

Magnetic

resonance

imaging

of

bone

marrow

in

sickle

cell

disease:

clinical,

hematologic,

and

pathologic

correlations.

Blood

1990;

75:

274-283.

12.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydin

LY,

Aydin

Y.

Digital

clubbing

may

be

an

indicator

of

systemic

atherosclerosis

even

at

microvascular

level.

HealthMED

2012;

6:

3977-3981.

13.

Yawn

BP,

Buchanan

GR,

Afenyi-Annan

AN,

Ballas

SK,

Hassell

KL,

James

AH,

et

al.

Management

of

sickle

cell

disease:

summary

of

the

2014

evidence-based

report

by

expert

panel

members.

JAMA

2014;

312:

1033-1048.

14.

Helvaci

MR,

Aydin

Y,

Ayyildiz

O.

Hydroxyurea

may

prolong

survival

of

sickle

cell

patients

by

decreasing

frequency

of

painful

crises.

HealthMED

2013;

7:

2327-2332.

15.

Platt

OS,

Brambilla

DJ,

Rosse

WF,

Milner

PF,

Castro

O,

Steinberg

MH,

et

al.

Mortality

in

sickle

cell

disease.

Life

expectancy

and

risk

factors

for

early

death.

N

Engl

J

Med

1994;

330:

1639-1644.

16.

Charache

S,

Scott

JC,

Charache

P.

''Acute

chest

syndrome''

in

adults

with

sickle

cell

anemia.

Microbiology,

treatment,

and

prevention.

Arch

Intern

Med

1979;

139:

67-69.

17.

Davies

SC,

Luce

PJ,

Win

AA,

Riordan

JF,

Brozovic

M.

Acute

chest

syndrome

in

sickle-cell

disease.

Lancet

1984;

1:

36-38.

18.

Mathers

CD,

Sadana

R,

Salomon

JA,

Murray

CJ,

Lopez

AD.

Healthy

life

expectancy

in

191

countries,

1999.

Lancet

2001;

357:

1685-1691.

19.

Helvaci

MR,

Ayyildiz

O,

Gundogdu

M.

Gender

differences

in

severity

of

sickle

cell

diseases

in

non-smokers.

Pak

J

Med

Sci

2013;

29:

1050-1054.

20.

Rennard

SI,

Drummond

MB.

Early

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease:

definition,

assessment,

and

prevention.

Lancet

2015;

385:

1778-1788.

21.

Schoepf

D,

Heun

R.

Alcohol

dependence

and

physical

comorbidity:

Increased

prevalence

but

reduced

relevance

of

individual

comorbidities

for

hospital-based

mortality

during

a

12.5-year

observation

period

in

general

hospital

admissions

in

urban

North-West

England.

Eur

Psychiatry

2015;

30:

459-468.

22.

Singh

G,

Zhang

W,

Kuo

YF,

Sharma

G.

Association

of

Psychological

Disorders

With

30-Day

Readmission

Rates

in

Patients

With

COPD.

Chest

2016;

149:

905-915.

23.

Danesh

J,

Collins

R,

Appleby

P,

Peto

R.

Association

of

fibrinogen,

C-reactive

protein,

albumin,

or

leukocyte

count

with

coronary

heart

disease:

meta-analyses

of

prospective

studies.

JAMA

1998;

279:

1477-1482.

24.

Mannino

DM,

Watt

G,

Hole

D,

Gillis

C,

Hart

C,

McConnachie

A,

et

al.

The

natural

history

of

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease.

Eur

Respir

J

2006;

27:

627-643.

25.

Mapel

DW,

Hurley

JS,

Frost

FJ,

Petersen

HV,

Picchi

MA,

Coultas

DB.

Health

care

utilization

in

chronic

obstructive

pulmonary

disease.

A

case-control

study

in

a

health

maintenance

organization.

Arch

Intern

Med

2000;

160:

2653-2658.

26.

Anthonisen

NR,

Connett

JE,

Enright

PL,

Manfreda

J;

Lung

Health

Study

Research

Group.

Hospitalizations

and

mortality

in

the

Lung

Health

Study.

Am

J

Respir

Crit

Care

Med

2002;

166:

333-339.

27.

McGarvey

LP,

John

M,

Anderson

JA,

Zvarich

M,

Wise

RA;

TORCH

Clinical

Endpoint

Committee.

Ascertainment

of

cause-specific

mortality

in

COPD:

operations

of

the

TORCH

Clinical

Endpoint

Committee.

Thorax

2007;

62:

411-415.

28.

Parfrey

NA,

Moore

W,

Hutchins

GM.

Is

pain

crisis

a

cause

of

death

in

sickle

cell

disease?

Am

J

Clin

Pathol

1985;

84:

209-212.

29.

Miller

ST,

Sleeper

LA,

Pegelow

CH,

Enos

LE,

Wang

WC,

Weiner

SJ,

et

al.

Prediction

of

adverse

outcomes

in

children

with

sickle

cell

disease.

N

Engl

J

Med

2000;

342:

83-89.

30.

Balkaran

B,

Char

G,

Morris

JS,

Thomas

PW,

Serjeant

BE,

Serjeant

GR.

Stroke

in

a

cohort

of

patients

with

homozygous

sickle

cell

disease.

J

Pediatr

1992;

120:

360-366.

31.

Helvaci

MR,

Kaya

H.

Effect

of

sickle

cell

diseases

on

height

and

weight.

Pak

J

Med

Sci

2011;

27:

361-364.

32.

Cole

TB,

Sprinkle

RH,

Smith

SJ,

Buchanan

GR.

Intravenous

narcotic

therapy

for

children

with

severe

sickle

cell

pain

crisis.

Am

J

Dis

Child

1986;

140:

1255-1259.

33.

Leikin

SL,

Gallagher

D,

Kinney

TR,

Sloane

D,

Klug

P,

Rida

W.

Mortality

in

children

and

adolescents

with

sickle

cell

disease.

Cooperative

Study

of

Sickle

Cell

Disease.

Pediatrics

1989;

84:

500-508.

34.

Poncz

M,

Kane

E,

Gill

FM.

Acute

chest

syndrome

in

sickle

cell

disease:

etiology

and

clinical

correlates.

J

Pediatr

1985;

107:

861-866.

35.

Sprinkle

RH,

Cole

T,

Smith

S,

Buchanan

GR.

Acute

chest

syndrome

in

children

with

sickle

cell

disease.

A

retrospective

analysis

of

100

hospitalized

cases.

Am

J

Pediatr

Hematol

Oncol

1986;

8:

105-110.

36.

Vichinsky

E,

Williams

R,

Das

M,

Earles

AN,

Lewis

N,

Adler

A,

et

al.

Pulmonary

fat

embolism:

a

distinct

cause

of

severe

acute

chest

syndrome

in

sickle

cell

anemia.

Blood

1994;

83:

3107-3112.

37.

Charache

S,

Terrin

ML,

Moore

RD,

Dover

GJ,

Barton

FB,

Eckert

SV,

et

al.

Effect

of

hydroxyurea

on

the

frequency

of

painful

crises

in

sickle

cell

anemia.

Investigators

of

the

Multicenter

Study

of

Hydroxyurea

in

Sickle

Cell

Anemia.

N

Engl

J

Med

1995;

332:

1317-1322.

38.

Charache

S.

Mechanism

of

action

of

hydroxyurea

in

the

management

of

sickle

cell

anemia

in

adults.

Semin

Hematol

1997;

34:

15-21.

|