|

Knowledge, Attitude and Practice

of Health Care Workers Towards HIV Patients

at Primary Health Care level in southwestern

Saudi Arabia: Twenty-five years after the initial

report

Hasan

M. Alzahrani (1)

Nabil J. Awadalla (2,3)

Rawan A. Hadi (4)

Fahd H. AlTameem (5)

Mona H. Alkhayri (4)

Amal Y. Moshebah (4)

Abdulaziz H. Alqarni (4)

Faisal E. Al-Salateen (4)

Abdulrahman A. Alqahtani (4)

Ahmad A. Mahfouz (2,6)

(1) Department of Emergency Medicine, King Khalid

University Medical City, Abha, Saudi Arabia

(2) Department of Family and Community Medicine,

College of Medicine, King Khalid University,

Abha, Saudi Arabia

(3) Department of Community Medicine, College

of Medicine, Mansoura University, Egypt

(4) Medical Intern/student, College of Medicine,

King Khalid University, Abha

(5) Ahad Rafidah Hospital, Saudi Arabia

(6) Department of Epidemiology, High Institute

of Public Health, Alexandria University, Egypt

Correspondence:

Professor Ahmad A. Mahfouz

Department of Family and Community Medicine,

College of Medicine,

King Khalid University, Abha,

Saudi Arabia

Email: mahfouz2005@gmail.com

Received: April 2019; Accepted: May 2019; Published:

June 1, 2019. Citation: Hasan Alzahrani et al.

Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Health Care

Workers Towards HIV Patients at Primary Health

Care level in southwestern Saudi Arabia: Twenty-five

years after the initial report. World Family

Medicine. 2019; 17(6): 4-8. DOI: 10.5742MEWFM.2019.93653

|

Abstract

The objective of the present study was

to critically review the existing knowledge,

attitude and practices of HCWs towards

HIV. A cross-sectional study was conducted

in Primary Health Care centers in Abha

and Khamis Mushait cities of Aseer region,

southwestern Saudi Arabia. All HCWs (physicians,

nurses, lab technicians and dentists)

were invited to participate in the study.

A validated self-administered structured

questionnaire was used to collect data

about HCWs’ personal and professional

characteristics; knowledge of HIV infection

and transmission; attitudes towards HIV/AIDS

patients and practices. A total of 372

HCWs were included in the study. Out of

them 23.9% were unable to identify tattooing

and ear piercing as methods for transmission.

A considerable proportion failed to mention

blood transfusion (3.8%), unprotected

sex (6.7%) and uncleanneedles (4.0%) as

possible methods for disease transmission.

Additionally, 36.8% of HCWs have a misconception

that kissing could transmit HIV and about

misbelieved that sharing eating and drinking

utensils (23.1%), swimming pool (18.8%)

and living with AIDs patients (17.5%)

could transmit infection. Stigmatizing

attitude was detected. In conclusion,

poor knowledge and stigmatizing attitude

toward HIV patients are evident in HCWs.

Health education programs should be adopted

to improve HCWs’ knowledge about

transmission mode and combat HIV stigma.

Key words:

HIV/AIDS; healthcare workers, Knowledge,

attitude, stigma, Saudi Arabia

|

According to recent WHO statistics, there were

globally approximately 36.7 million people living

with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

at the end of 2016(1). A recent report by the

Saudi Ministry of Health in 2018, including

data obtained from 20 HIV treatment centers

located in different regions of the Kingdom,

showed that there were 6,256 people living with

HIV and knew their status by the end of 2017,

which is equivalent to 76% of the estimated

number of people living with HIV in Saudi Arabia

(2).

A study performed in 2015 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia,

among the general population showed lack of

proper knowledge about the disease and more

than 40% think that HIV positive people should

be isolated (3). Similarly, a study among male

dental students in Saudi Arabia showed lack

of knowledge regarding HIV/AIDS transmission

and means for prevention in addition to unfavorable

attitudes towards HIV/AIDS individuals (4).

It was well known that the traditional primary

health care approach of health promotion and

disease prevention that focuses on case-finding,

continuity of care and problem resolution, adapts

well to HIV/AIDS. Primary care is holistic,

patient based, and has as its focus healing

rather than cure. Primary care physicians have

a role in the prevention of HIV infection, in

identifying asymptomatic seropositive people,

in offering early therapeutic interventions,

in the early detection of opportunistic infections

and HIV-related malignancies, and in the ongoing

management of chronic ill-health. There is also

a role for primary care physicians in the psychosocial

management of people with HIV/AIDS, in supporting

those close to the patient, and in educating

the community in general about the social parameters

of HIV/AIDS (5).

In 1995 two published articles addressed the

awareness of HIV among primary health care workers

in Aseer region, Saudi Arabia. They found massive

defects in their knowledge (6, 7). Recent data

regarding knowledge, attitude and practices

of primary healthcare workers in Saudi Arabia

in general and in the Aseer region in particular,

are scarce and even lacking. The aim of the

present work is to study the current knowledge,

attitude and practices (KAP) of primary healthcare

workers towards HIV in Abha and Khamis Mushait

cities of Aseer region, Saudi Arabia.

The present cross-sectional study was conducted

in primary health care centers in Abha and Khamis

Mushait cities of Aseer region, southwestern

Saudi Arabia in 2017. All health care workers

(physicians, nurses, lab technicians and dentists)

were invited to participate in the study. Administrative

personnel not in direct contact with patients’

care were not included.

Data were collected through self-administered

validated structured questionnaire (4). The

questionnaire covered the following four major

areas; demographic data including age, sex,

and nationality, professional data including

type of profession, how long they have been

working, have they provided care towards HIV

patients. The questionnaire included 14 closed-ended

question about knowledge of HIV infection and

transmission. The questionnaire also covered

attitudes regarding treating HIV patients, the

right of health personnel to practice and willingness

to treat.

Data were verified, coded and analyzed using

the Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS). Frequencies and percentages were used

to present the results.

The study protocol was approved by the research

ethical committee of King Khalid University

(REC#2017-04-03). All the necessary official

permissions were obtained before data collection.

Written consent was taken from the participants.

Collected data were kept strictly confidential

and used only for the research purposes.

Description

of

the

Study

Sample

The

present

study

included

372

Health

Care

Workers

(HCWs).

Almost

half

of

the

study

sample

were

from

Abha

city

(199,

53.5%)

and

the

rest

were

from

Khamis

Mushait

city.

The

majority

of

HCWs

were

females

(228,

61.3%)

and

Saudis

(318,

85.5%).

The

highest

frequent

age

group

was

20-30

years

(181,

48.7%)

followed

by

31

to

40

years

(149,

40.1%).

Dentists

represented

47.6%

(177)

of

the

study

sample

followed

by

physicians

(95,

25.5%)

and

nurses

(78,

21.0%).

The

highest

frequent

period

of

work

was

5-10

years

(160,

43.0%)

followed

by

less

than

5

years

(105,

28.2%).

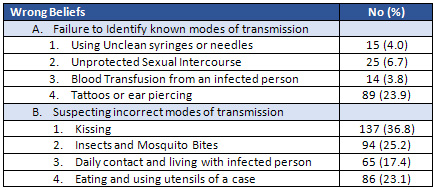

Failure

to

identify

the

well-known

modes

of

HIV

transmission

Table

1

shows

the

wrong

beliefs

among

HCWs

regarding

HIV

modes

of

transmission.

Regarding

the

failure

to

identify

the

well-known

modes

of

HIV

transmission,

the

highest

failed

mode

to

be

mentioned

was

via

tattoos

or

ear

piercing

(89,

23.9%).

The

least

unidentified

mode

was

blood

transfusion

from

an

infected

person

(14,

3.8%).

On

the

other

hand,

unprotected

sex

and

using

unclean

needles

was

not

mentioned

by

(6.7

%

and

4.0%,

respectively).

No

significant

differences

(P>

0.05)

were

found

by

gender,

nationality,

age,

profession

and

duration

of

employment.

Table

1:

Wrong

Beliefs

in

Modes

of

transmission

of

HIV

as

mentioned

by

PHCCs

workers

in

the

study

area,

2017

Suspecting

Incorrect

modes

of

HIV

transmission

Regarding

incorrect

knowledge

of

modes

of

HIV

transmission,

the

highest

wrong

modes

mentioned

by

HCWs

was

via

kissing

(137,

36.8%),

followed

by

mosquitos

and

other

insects

bites

(94,

25.2%)

and

via

sharing

plates,

cups,

and

utensils

(86,

23.1%).

The

least

mentioned

incorrect

modes

of

transmission

were

via

sitting

in

a

hot

tub

or

a

swimming

pool

(70,

18.8%),

via

living

with

a

person

with

AIDs

(65,

17.5%)

and

through

the

air

(coughing

or

staying

in

the

same

room

as

someone

infected

with

HIV

(56,

15.1%).

No

significant

differences

(P>

0.05)

were

found

by

gender,

nationality,

age,

profession

and

duration

of

employment.

Other

wrong

knowledge

mentioned

by

HCWs

were

the

presence

of

a

vaccine

that

can

stop

getting

HIV

(38,

10.2%)

and

that

the

people

who

have

been

infected

with

HIV

quickly

show

serious

signs

of

being

infected

(63,

16.9%).

Attitudes

towards

HIV

Patients

Regarding

attitudes

towards

HIV

patients,

the

highest

frequent

response

was

feeling

uncomfortable

when

eating

meals

prepared

by

a

person

with

HIV

(209,

56.2%).

Almost

one

out

of

each

ten

HCWs

(39,

10.5%)

stated

that

HIV

patients

should

be

ashamed

of

themselves,

they

deserve

what

they

get

(32,

8.6%)

and

only

promiscuous

people

get

HIV

(28,

7.5%).

On

the

other

hand,

more

than

two-thirds

of

HCWs

(295,

79.3%)

mentioned

that

they

were

empathetic

with

HIV

patients.

Preventive

activities

during

practice

Regarding

preventive

activities

during

practice,

one-third

of

HCWs

(142,

38.2%)

mentioned

that

spills

of

blood

or

body

fluids

are

decontaminated

by

sodium

hypochlorite

solution.

Two-thirds

(267,

71.8%)

mentioned

that

the

work

provides

protective

equipment

for

HCWs

to

prevent

the

spread

of

HIV

and

identified

the

use

of

liquid

detergent

and

running

for

hand

washing

to

prevent

the

spread

of

HIV

(243,

65.3%).

|