Public

Assessment of Social and Economic Rehabilitation

Component of Leprosy Control Programmes in Anambra

and Ebonyi States of Southeast Nigeria

Nwankwo,

Ignatius Uche

Correspondence:

Nwankwo, Ignatius Uche, Ph.D.

Department of Sociology/Anthropology

Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Anambra State,

Nigeria

Email:

iunwankwo@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Three major objectives informed this research

paper. The first was to find out the types

of social and economic rehabilitation

(SER) activities available to persons

affected by leprosy (PAL) in Anambra and

Ebonyi states of Southeast Nigeria. The

second is to find out the nature of public

perception on adequacy and outcomes of

social and economic rehabilitation packages

for leprosy cases, while the third is

to verify public view about adequacy or

otherwise of funding for social and economic

rehabilitation of persons affected by

leprosy in the two states. The study adopted

a cross-sectional survey design. Quantitative

data was generated through structured

questionnaire schedule administered on

1116 study participants. The participants

were selected through a combination of

cluster and simple random sampling methods.

Qualitative data were generated through

two instruments. These were Focus Group

Discussion (FGD) administered on persons

affected by leprosy and In-Depth Interview

(IDI) of leprosy control staff and officials

from both World Health Organization and

the donor agency supporting leprosy control

in the two states. The Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software

was employed in analysis of data. Frequency

tables, percentages, bar charts, chi-square

and multiple regressions were used for

presentation, analysis and in testing

the stated hypotheses. It was found that

only 25.5% of the respondents acknowledged

availability of SER component which is

institutional rather than community based.

Furthermore, most respondents assessed

SER activities in leprosy control in the

two states as largely unsuccessful One

hypothesis test showed that more respondents

with low income perceived a link between

adequate funding and effective leprosy

control programme than those with higher

levels of income (X2=190.427,df=70,p=0.000).

It was recommended that aggressive public

enlightenment through public, private

and local media; incentive package for

health workers and extensive socio-economic

empowerment for effective rehabilitation

of patients be adopted to enhance leprosy

control in Anambra and Ebonyi states.

Key words:

Assessment, Leprosy, Leprosy Control,

Social and Economic Rehabilitation, Empowerment

|

Leprosy is one of the oldest diseases of mankind.

It has a unique social dimension that often

culminates in the total destabilization of the

social life of its victims. From the earliest

times, leprosy has been a disease set apart

from others. Its victims and even their care

givers are ostracised in many societies. Although

the disease seldom kills (Bryceson and Pfaltzgraff

1990), it remains a public health problem and

cause of morbidity especially in developing

countries like Nigeria. The disease is also

one of the leading causes of permanent disability

worldwide and has over the year's left a terrifying

memory of mutilation, rejection and social exclusion

(Lockwood, 2000). There are serious problems

confronting control programmes and victims of

leprosy in affected countries. In Nigeria, Sofola

(1999) expresses concern at poor funding of

leprosy control activities. There is also an

enormous problem of policy inconsistency in

the area of leprosy control. The initial emphasis

of control activities was on isolation of victims

at Leprosaria where specialist health staff

attend to them. The gains of this original focus

were as yet not fully tapped when a shift in

policy was initiated. According to Eboh (1999),

the old arrangement contributed to the difficulty

in achieving the present policy thrust of integrating

leprosy control programme with general primary

health care. It also resulted in the failure

of newer measures to attain optimal results,

since most people still adhere to the old practices.

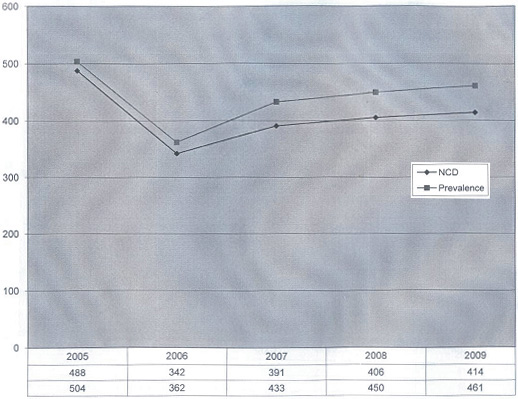

Particularly disturbing is the graph below from

World Health Organization (WHO) Southeast of

Nigeria Office (2010), which shows that the

Southeast zone of Nigeria has consistently recorded

increases (rather than decreases) in both new

case detection and prevalence of leprosy since

2006-2009. This raises fundamental questions

about the potency of leprosy control programme

and whether leprosy should be classified as

a re-emerging disease in the area and for what

reasons.

Figure 1: Leprosy New Case Detection (NCD)

and Prevalence, 2005 - 2009 for South-east Zone

of Nigeria

Source: World Health Organisation, Southeast

Zonal Office, Enugu Nigeria, (2010).

Furthermore, poor leprosy control outcomes have

persisted to the extent that a former World

Health Organization's Country Representative

in Nigeria, Dr Peter Ekiti lamented that in

2008; only 14% of the estimated new leprosy

cases in Nigeria were actually detected and

enrolled for treatment (Ekiti, 2010). Similarly,

Adagba (2011) and was very critical that prevalence

of leprosy among children in Nigeria is still

high and unacceptable.

In 2008, Nigeria was ranked at the fifth position

among nations with high leprosy burden in the

world, and in Africa, second only to Republic

of Congo (W.H.O, 2008). Nigeria's registered

prevalence of leprosy as at 2002 was 5890 (FMOH,

2004). It declined to 5381 by the beginning

of 2008 (W.H.O, 2008) and further to 3913 cases

at the end of 2010 (Adagba, 2011). The above

situation appears to be compounded by enormous

fear of leprosy among the Nigerian populace

(Ogoegbulem, 2000). In many parts of Nigeria,

despite the existence of leprosy control activities

since the pre-Dapsone era of 1900-1947, the

fear and stigma of leprosy remains high and

separates persons affected by leprosy (PAL)

from their fellows. Nicholls (2000) had similarly

observed that in both Eastern and Western cultures,

fear of leprosy has existed from ancient times.

On the other hand, Osakwe (2004) regretted

that community participation which is a crucial

element in leprosy control has remained weak

in Nigeria. Consequently, community response

or behaviour toward those suffering from leprosy

is characterized by avoidance, insult and rejection

of victims. Even discharged leprosy ex-patients

are not spared of these actions that also constitute

violation of human rights.

Nicholls (2000) further observes that leprosy

more than any other disease has caused individuals

to leave their families and communities and

be forced to live as outcasts in separate colonies

and settlements. Some of such colonies or settlements

are still operating at Okija, Otolo-Nnewi, and

Amichi communities in Anambra state; and at

Mile Four Abakaliki and Uburu communities at

Ebonyi state. There are others at other parts

of Nigeria. Their continued operation is an

evidence of the failure of the National Leprosy

Control Programme to implement home based or

ambulatory care arrangement where most patients

access treatment from their homes, except those

who are in critical conditions and require hospitalization.

The advantage of home based care in reducing

segregation and facilitating the new thrust

toward Community Based Rehabilitation (CBR)

cannot be over-emphasized. Also problematic

is the fact that at such colonies, inmates live

in dilapidated structures surrounded by bushes

in more or less inhuman conditions. An integrated

and effective leprosy control programme has

a responsibility to provide conducive living

and treatment environment to persons affected

by leprosy. It should indeed address their bio-medical,

social and economic needs.

Accordingly, Smith (2000) notes that Social

and Economic Rehabilitation (SER) is a major

priority in any leprosy control effort. This

emphasis according to W.H.O (1999) is aimed

at addressing problems of stigmatization, inability

to work, social isolation and economic dependency.

However, Ogbeiwi (2005) reports that the SER

component of Nigeria's National Leprosy Control

Programme does not reflect the priority it deserves;

hence it is yet to make any appreciable impact.

Persons affected by leprosy in Southeast Nigeria

are already burdened by medical and bio-physical

challenges posed by the disease. Their having

to further contend with very serious social,

economic and psychological problems arising

from societal perception and consequent reactions

to their predicament are weighty. Ogoegbulem

(2000), reports that they often encounter severe

loss of dignifying self concept and social recognition.

They are not usually welcome at public functions.

On rare occasions where these patients or ex-patients

force themselves unto a gathering, this might

result either in an abrupt dismissal of participants

or in avoidance of any form of physical contact

with them. Indeed, Nigerians are afraid to sit

near persons affected by leprosy at churches,

markets, vehicles; village squares and so on.

They are also reluctant to marry from families

of known leprosy patients (Ogoegbulem, 2000).

The lack of friendship and other forms of association

as well as divorce or threats of divorce from

spouses constitute part of the numerous social

problems faced by persons affected by leprosy.

The control programme in Nigeria ought to find

answers to these myriad of problems.

In another development, the value of the use

of economic empowerment as a tool of leprosy

control has been extensively documented by scholars.

Examples of these are Nash (2001); Federal Ministry

of Health (FMOH, 1997); Macaden (1996); Pearson

(1988). However, Ogbeiwi (2005) notes that the

approach is yet to be adequately exploited in

Nigeria. This is despite the fact that the disease

is widely known to have devastating effect on

the economic life of its victims. For instance,

Rafferty (2005), notes that leprosy destroys

productivity of victims through series of disablement

or lack of physical function which it engenders.

The situation is complicated by the fact that

societies avoid goods and services offered by

persons affected by leprosy. Such poor patronage

tends to de-motivate the victims as it forces

them to abandon their trades.

In the light of the above and given the inadequacy

of economic support package from the control

programme, persons affected by leprosy often

resort to begging on the streets as means of

self-sustenance. Consequently, markets, bus-stops,

motor-parks, entrances to churches, banks and

offices are littered with these destitute. This

constitutes a threat to public health. It also

generates public outcry about the welfare of

persons affected by leprosy which the control

programme has a responsibility to protect.

The lukewarm attitude of health workers toward

leprosy control activities (Adagba, 2011) is

also a major challenge facing the control programme

Poor allowances, negative cultural reactions

towards leprosy and fear of contracting the

disease negatively affect the disposition of

health workers to committed service. Consequently,

the workers have not prosecuted aspects such

as public health education and ulcer dressing

in leprosy with sufficient zeal and enthusiasm.

Because of this, individuals and groups have

expressed deep concerns about poorly maintained

leprosy ulcers often exuding odorous discharges

and attracting flies which have become regular

feature of persons affected by leprosy. Leprosy

victims endure the pain of such ulcers as they

move about to solicit for alms. These patients

are also unsightly and degrade the aesthetic

beauty of neighbourhoods by their low level

of personal and environmental hygiene.

The gender dimension and social stratification

implications of leprosy are other areas which

the control programme is yet to adequately address.

The gender dimension of leprosy is such that

women encounter the severest forms of social,

economic and psychological consequences compared

to their male counterparts upon diagnosis of

leprosy (Kaur and Rameshi 1994; Grand 1997;

Rao, Garole and Walawalker 1996). Women do not

also occupy important positions in self help

groups formed by patients in their colonies.

This is especially so in a highly patriarchal

society like the South-eastern part of Nigeria

where subservient position and economic dependence

of women on men are culturally defined. Sofola

(1999), observes that in many leprosy colonies

in Nigeria, women affected by leprosy get smaller

portions of land for cultivation compared to

the males. Observation of the current situation

suggests that equality of the sexes in accessing

rights and privileges accruable from leprosy

control programme remains defective in Nigeria.

Valsa (1999) examined social acceptance and

social stratification implications of leprosy.

He found that those affected could lose their

position in the social ranking of society. They

could be barred from taking important titles

or occupying positions of authority and honour.

They are not allowed to officiate important

occasions or to perform important rites associated

with such occasions even when it is their right

by birth in the community to do so (Kaufman,

Neville and Miriam, 1993; Ogoegbulem, 2000).

Expectations that leprosy control programme

in Nigeria would reverse the trend so far remains

a mirage. Above all, although WHO introduced

Multiple Drug Therapy (MDT) since 1985 as drug

of choice for leprosy (FMOH, 2008), it appears

that the treatment component of leprosy control

programmes have failed to respond to the needs

of persons affected by leprosy for cure or full

recovery without any deformity. The situation

is such that it is often difficult to distinguish

between victims who accessed treatment services

from those who did not due to permanent disabilities.

Also, their social and economic predicaments

are similar in most respects thus indicating

that the rehabilitation process of those who

accessed treatment services was not successful.

Ogoegbulem (2000) observes that victims of leprosy

who have completed treatment in parts of Nigeria

are not fully reunited and reintegrated into

the society and generally lack means of sustenance.

The seemingly resilient nature of leprosy and

its associated problems in Nigeria generate

doubts about the sincerity and commitment of

National Leprosy Control Programmes toward eradication

of leprosy by World Health Organization's global

target date. It is against the backdrop of the

above background and problems that the research

was undertaken to investigate public assessment

of social and economic rehabilitation component

of leprosy control programmes in Anambra and

Ebonyi states of Southeast Nigeria.

| BRIEF

REVIEW

OF

LITERATURE

ON

ROLE

OF

SOCIAL

AND

ECONOMIC

REHABILITATION

(SER)

IN

LEPROSY

CONTROL |

The role of rehabilitation

as one of the most important

aspects of leprosy control

has been emphasized

by several scholars

(see Nash 2001; Macaden

1996; Pearson 1988;

FMOH 1997). According

to Nash (2001), rehabilitation

of persons affected

by leprosy is a process

that helps them to feel

accepted, valued and

included in their community.

It assists them live

as normal a life as

possible. Pearson (1988)

defines it as the diagnosis,

treatment and prevention

of dehabilitation occasioned

by leprosy.

Rehabilitation for leprosy

patients usually involves

physical, social, economic

and psychological components

(FMOH, 1997). Pearson

(1988) gave reasons

for the multiple levels

of emphasis. He noted

that leprosy can cause

its victims to lose

physical forms, family

and place in society.

It can also cause them

to lose their work,

other means of livelihood

and their self respect.

These situations Pearson

says require detailed

rehabilitation response.

According to Macaden

(1996), rehabilitation

services for persons

affected by leprosy

could be organised in

three ways as follows:

a. Institution Based

Rehabilitation -

where patients lived

in and accessed rehabilitation

service only at the

health institution,

usually a Leprosarium.

Patients were not integrated

into their family or

community.

b. Outreach Services

- obtainable at camps,

outreach service points

and patient's home

c. Community Based

Rehabilitation (CBR).

This is the current

emphasis both in Nigeria

and globally (FMOH,1997).

It seeks not only to

help people overcome

their impairments, but

also to help them to

settle back fully in

their communities. CBR

in leprosy control adopts

an integrated approach.

It involves community

participation in provision

of rehabilitation services

to patients with diverse

social, economic, physical

and psychological needs

(FMOH, 1997).

Macaden (1996) similarly

stressed that CBR in

leprosy transfers to

members of the family

of the patient and the

community in which they

live, the skills needed

to manage physical impairments

and to provide vocational

training and placement.

On his part Nash (2001)

notes that the role

of community participation

in CBR is very crucial

to the extent that sometimes,

the community needs

as much rehabilitation

as the persons affected

by leprosy in order

to creditably discharge

their role in rehabilitation.

Smith (2000) also saw

social and economic

rehabilitation (SER)

of people affected by

leprosy as a major priority

that requires considerable

emphasis by control

programmes. This emphasis

according to W.H.O (1999),

is sequel to problems

of stigmatization, shame,

isolation, inability

to work or marry, dependency

on others for care and

financial support which

persons affected by

leprosy are exposed

to in many societies.

Nash (2001) reports

that in Nigeria, adherence

to guidelines on social

and economic rehabilitation

has been useful in restoration

of normal social and

economic life of persons

affected by leprosy.

He observed that preliminary

need assessment of patients

and active community

participation have ensured

that they fitted into

new socio-economic roles

like poultry keeping,

soap making, weaving,

tailoring, shoe-making

etc. Such roles he says,

restores social acceptance

and respect to patients.

Chukwu (2004) also looked

at the practice of CBR

in Nigeria. He commended

German Leprosy Relief

Association's support

towards social and economic

rehabilitation of persons

affected by leprosy

across fourteen states

in the Southeast and

Southwest of Nigeria.

He noted that the organization

has built houses, and

paid subsistence allowance

to patients. They have

also bought motorcycles

for public transport

services and given capital

to enable persons affected

by leprosy to start

their own businesses.

Despite these supports

by German Leprosy Relief

Association, Chukwu

(2004) insists that

contributions of the

rehabilitation arm of

leprosy control remains

insignificant across

most of Nigeria. According

to him, persons affected

by leprosy experience

various forms of discrimination

on account of the disease.

Many of them have no

means of subsistence

and depend on begging

to survive.

The

following

research

questions

guided

the

study:

(a)

What

types

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

programmes

are

available

to

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states?

(b)

What

are

the

perceived

outcomes

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states?

(c)

How

do

people

of

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

States

of

Southeast

Nigeria

perceive

the

level

of

funding

for

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

their

area

in

terms

of

its

adequacy?

The

labelling

theory

is

relevant

in

explaining

the

problem

of

leprosy

in

the

study

area.

Labelling

theory

is

particularly

useful

in

the

analysis

of

the

qualitative

data.

This

is

because

of

its

emphasis

on

social

constructionism.

Labelling

theory

was

also

adopted

as

the

theoretical

platform

because

its

basic

postulations

explicitly

relate

to

the

process

of

social

definition

and

stigma

surrounding

leprosy.

These

are

central

issues

to

leprosy

problem

in

society.

Negative

cultural

imaging

of

leprosy,

and

the

manner

in

which

societies

through

the

instrument

of

language

defined

leprosy

as

a

curse

from

gods,

or

as

disease

of

the

unclean,

have

adverse

consequences

for

its

control.

People

are

reluctant

to

be

associated

with

the

disease

whether

as

patients

or

health

workers

because

of

the

stigma

attached

to

it.

It

is

therefore

not

surprising

that

despite

its

long

history

and

availability

of

free

and

effective

drugs

(FMOH,

2004),

leprosy

remains

a

public

health

problem

in

our

environment.

Adverse

religious

perspectives

on

leprosy

have

also

done

much

to

intensify

leprosy

stigma

and

worsen

problems

arising

from

leprosy

in

our

society.

Awofeso

(2005)

notes

that

biblical

references

like

Leviticus

13:45;

Numbers

5:2;

and

2

Kings

26:21

create

an

impression

that

leprosy

is

a

dreaded

disease

associated

with

sinners.

He

observes

also

that

Buddhist

teaching

on

Karma

make

it

acceptable

for

believers

to

frame

leprosy

sufferers

as

sinners

in

their

past

incarnation.

These

conceptions

compounded

by

low

level

of

education,

constitute

major

obstacles

to

leprosy

control.

Labeling

also

offers

adequate

explanation

to

why

persons

affected

by

leprosy

try

to

cover

up

their

disease

and

fail

to

avail

themselves

of

early

treatment.

The

situation

results

in

severe

deformities

and

complications.

The

theory

also

accounts

for

the

lack

of

enthusiasm

of

health

workers

to

leprosy

work,

and

for

low

level

of

integration

of

patients

into

their

community.

The

study

located

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states,

randomly

selected

out

of

five

states

of

Southeast

Nigeria,

adopted

cross-sectional

survey

design.

The

Southeast

zone

of

Nigeria

was

purposively

selected

because

of

the

steady

increase

(rather

than

decrease)

in

number

of

leprosy

cases

registered

annually

in

the

zone

during

2006

-

2009

(see

Table

1

below).

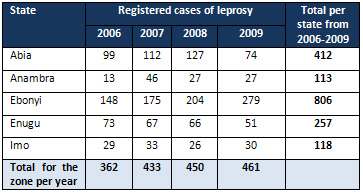

Table

1:

Distribution

of

Leprosy

cases

according

to

States

in

the

Southeast

Zone

of

Nigeria

during

the

period

2006-2009

Source:

World

Health

Organisation,

Southeast

Area

Office,

Enugu

-

Nigeria,

(2010).Leprosy

New

Case

Detection,

Case

Detection

Rate

and

Prevalence

Rate

for

Southeast

Zone,

2006-2009.

The

indigenous

ethnic

group

in

the

two

states

are

the

Igbo

of

whom

Ifemesia

(1979)

observes

that

their

territory

covers

an

area

of

over

15,800

square

miles.

Nwala

(1985)

circumscribed

the

area

between

6o

and

8½o

East

longitude

and

4½o

and

7½o

North

latitude.

He

noted

that

Igbo

land

is

very

densely

populated.

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states

are

rich

in

natural

resources

and

arable

soil.

Land

cultivation,

trading,

arts

and

crafts,

animal

husbandry

and

civil

service

are

major

economic

activities

in

the

two

states.

However,

people

of

Anambra

state

are

more

involved

in

entrepreneurship

and

commerce

whereas

Ebonyi

state

is

notable

for

agricultural

prowess

(Uzozie

2002;

Onokala

2002).

There

is

an

elected

civilian

government

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states

whose

role

in

governance

of

the

area

is

complemented

by

socio-political

structures

and

pressure

groups

that

characterize

Igbo

traditional

societies

like

gerontocracy,

village

assembly,

titled

men,

women

groups

all

of

which

are

relevant

to

grass

root

administration

in

both

states.

Similarly,

Christianity

enjoys

greater

followership

in

the

area

but

exists

side

by

side

with

traditional

religion

which

still

has

many

adherents.

The

total

population

of

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states

as

at

2006

national

population

and

housing

census

in

Nigeria

was

6,354,775

made

up

of

3,182,140

males

and

3,172,791

females.

However,

the

study

population

consisted

of

only

adults,

defined

as

persons

aged

18

years

and

above.

There

are

about

3,515,370

adults

in

the

area

which

represented

57.2%

of

the

total

population.

A

sample

size

of

1116

respondents

(558

from

each

state)

constituting

about

0.32%

of

the

study

population

was

used

to

generate

quantitative

data

in

this

study.

The

sample

was

adequate

for

applicable

statistical

tests.

The

sample

also

accommodated

geographical

spread

and

rural-urban

bias

at

the

ratio

of

2:1.

Qualitative

data

was

generated

from

64

respondents

made

up

of

52

persons

affected

by

leprosy

(26

from

each

state);

6

LGA

leprosy

control

supervisors

(3

from

Anambra

and

3

from

Ebonyi)

on

the

basis

of

one

supervisor

per

selected

LGA

in

each

state;

4

officers

from

Leprosy

Control

Units

of

Ministry

of

Health

in

the

two

states

(2

from

each

state)

and

one

official

each

from

Donor

Agency

supporting

leprosy

control

and

World

Health

Organization.

The

cluster

(multistage)

sampling

approach

involving

division

of

the

population

or

geographical

area

into

units

and

selecting

specific

number

of

these

units

by

simple

random

sampling

techniques

was

adopted

for

selection

of

members

of

the

public.

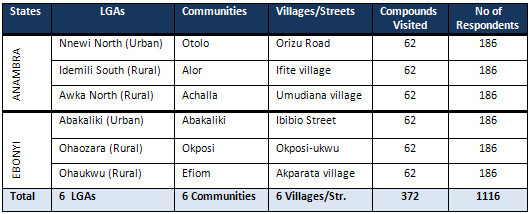

Table

2:

Local

Government

Areas

(LGA),

Communities

and

Villages

used

in

the

study

Source:

Field

Survey,

2010

Source:

Field

Survey,

2010

.

Three

instruments

were

combined

in

the

study

for

optimum

results.

Quantitative

data

were

collected

through

questionnaire

with

closed

and

open

ended

items

administered

on

a

one-on-one

(other

administered)

basis

with

all

respondents.

The

instrument

was

pre-tested

by

the

researcher

and

five

Field

Assistants

pre-trained

for

the

purpose

in

four

sessions

outside

the

study

communities,

at

Eziani-

Ihiala,

in

Ihiala

LGA

of

Anambra

state

with

40

compounds/

households

and

120

respondents.

This

was

to

ensure

reliability

and

suitability

of

the

instrument

to

meet

study

objectives.

The

language

of

administration

was

Igbo,

spoken

in

the

area,

because

there

were

many

respondents

who

could

not

read,

write

or

understand

English

language.

Nonetheless,

English

was

used

where

any

respondent

showed

preference

for

English

language.

The

instrument

which

was

originally

in

English

was

translated

into

the

local

language,

which

is

Igbo

and

retranslated

into

English,

to

provide

both

Igbo

and

English

versions.

Same

sex

administration

of

questionnaire

was

carried

out

to

prevent

any

cultural

barriers

and

permit

free

discussion

or

responses

to

questionnaire

items.

Qualitative

data

were

gathered

through

Focus

Group

Discussions

(FGD)

and

In-Depth

Interview

(IDI).

The

FGD

involved

persons

affected

by

leprosy

(patients)

who

were

not

respondents

in

the

questionnaire

study.

There

were

four

FGD

sessions

with

6-12

participants

per

session.

Participants

were

segmented

along

gender.

Two

FGD

sessions

were

conducted

at

Mile

Four

Hospital

Abakaliki,

Ebonyi

state

for

male

and

female

groups

respectively.

The

other

two

were

conducted

at

Fr

Damian

Tuberculosis

and

Leprosy

Referral

Hospital

Nnewi,

Anambra

state.

Both

institutions

were

convenient

to

both

in

and

out-

patients.

Each

session

was

held

on

leprosy

clinic

days

which

are

usually

market

free

days

in

the

area

of

study.

The

moderator

of

the

FGD

was

of

the

same

sex

with

their

FGD

group

and

worked

with

the

co-operation

of

leprosy

control

staff

on

duty.

There

were

also

two

assistants

for

each

FGD

session.

The

language

of

administration

was

Igbo.

A

tape

recorder

and

field

notebook

was

used

to

record

proceedings.

One

assistant

took

notes

in

the

course

of

each

session

while

the

other

served

as

Tape

Recorder

Operator.

The

second

qualitative

tool

was

the

conduct

of

In-Depth

Interview

(IDI).

It

was

used

to

interrogate

four

officials

who

are

major

stakeholders

in

leprosy

control

project.

These

were

Leprosy

Control

Officers

or

their

assistant

in

the

two

states,

Medical

Officer

of

German

Leprosy

Relief

Association,

and

W.H.O's

Principal

Officer

for

Leprosy

Control

for

Southeast

Area

of

Nigeria.

The

interview

schedule

was

unstructured

and

tailored

to

generate

detailed

information

on

the

subject

of

study.

The

in-

depth

interviews

were

conducted

by

the

researcher

and

two

of

the

assistants

at

the

offices

of

the

stated

officials.

Tape

recorder

and

field

note

book

were

used

to

record

responses

from

interviewees.

The

interview

schedule

guided

the

interview

which

was

conducted

in

English

language

due

to

respondents'

preference

and

literacy

level.

Quantitative

data

gathered

in

the

course

of

research

were

analysed

with

the

help

of

the

Statistical

Package

for

the

Social

Sciences

(SPSS)

software.

Descriptive

statistics

like

frequency

distribution

tables,

mean,

median,

percentages

and

bar-charts

were

used

to

interpret

data.

One

correlation

analysis

(the

chi-square)

was

employed

in

hypotheses

test.

On

the

other

hand,

qualitative

data

generated

through

FGD

and

IDI

were

transcribed

and

organised

under

different

aspects

of

the

discussion

and

used

to

explain

quantitative

data

where

applicable.

One

thousand,

one

hundred

and

sixteen

(1116)

questionnaires

were

administered

out

of

which

1104

were

used

for

analysis

after

coding

and

cleaning/

editing

all

validly

completed

and

returned

questionnaire

schedules.

Results

and

their

analysis

were

presented

according

to

research

questions

for

easy

comprehension.

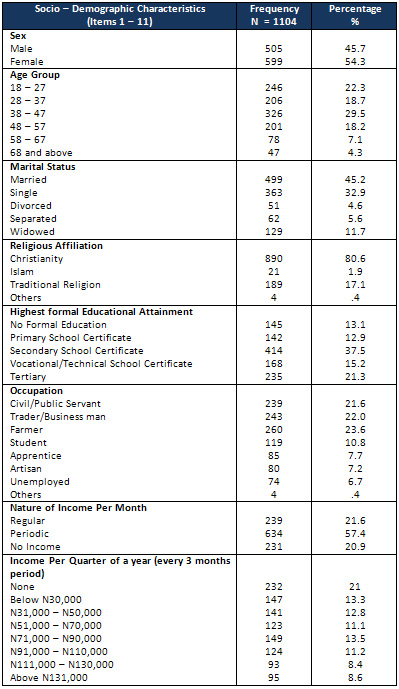

(a)

Socio-Demographic/Personal

Characteristics

of

Respondents

The

socio-demographic

profile

of

respondents

is

presented

in

Table

3

below.

Table

3:

Distribution

of

Respondents

by

Socio-Demographic

Characteristics

Source:

Field

Survey,

2010.

Table

3

shows

that

females

constituted

54.3%

of

the

total

respondents,

while

the

males

constituted

45.7%.

Many

of

the

respondents

(29.5%)

fall

within

the

age

bracket

of

38

-

47

years.

The

least

number

of

respondents

(4.3%)

came

from

the

age

-

group

of

45

years

and

above.

However,

the

modal

and

median

ages

were

41

and

45

years

respectively.

Also,

the

mean

age

of

respondents

was

40.33

years

with

a

standard

deviation

of

13.45.

With

regard

to

the

marital

status

of

the

respondents,

45.2%

were

married

while

32.9%

are

single.

The

widowed,

separated

and

divorced

respondents

were

very

few

(11.7%,

5.6%

and

4.6%

respectively).

The

large

number

of

married

respondents

illuminates

the

high

premium

placed

on

marriage

and

family

institution

in

the

area.

Similarly,

divorce

is

low

probably

because

the

value

system

abhors

it.

Being

married

and

having

stable

marriage

are

accorded

high

esteem

and

social

honour

among

Igbo

people.

With

respect

to

religious

affiliation,

the

table

clearly

shows

that

more

than

three-quarters

of

the

respondents

(80.6%)

were

Christians.

A

few

of

the

respondents

belong

to

other

religious

groups

including

Islam

(1.9%),

traditional

religion

(17.1%)

and

other

unspecified

groups

(.4%).

In

terms

of

highest

formal

educational

attainment,

those

who

possess

secondary

school

certificate

constituted

37.5%

of

the

respondents.

Other

categories

of

educational

attainment/

certification

were

tertiary

(21.3%),

vocational/technical

school

(15.2%),

and

primary

school

certificate

holders

(12.9%).

With

only

13.1%

of

the

respondents

without

any

form

of

formal

education,

the

literacy

level

in

the

area

is

relatively

high.

However,

more

respondents

from

Anambra

state

(27.7%)

had

tertiary

education

than

those

from

Ebonyi

state

where

only

15%

had

tertiary

education.

The

respondents

were

almost

equally

divided

across

three

major

occupations.

These

are

farmers

(23.6%),

traders

(22%),

and

civil/public

servants

(21.6%).

Students,

apprentices,

artisans

and

the

unemployed

were

few.

They

constituted

10.8%,

7.7%,

7.2%,

and

6.7%

respectively.

The

occupational

distribution

of

the

respondents

highlighted

above

mirrors

the

popular

description

of

Ebonyi

state

as

food

basket

(major

agricultural

zone)

of

the

nation,

and

Anambra

state

as

center

for

commerce

and

other

entrepreneurial

activities.

The

predominance

of

farmers

and

traders

in

the

area

of

study

is

therefore

not

a

major

surprise.

However,

the

nature

of

income

reveals

that

most

of

the

respondents

(57.4%)

earn

periodic

income;

21.6%

earn

regular

income

on

monthly

basis,

while

20.9%

earn

no

income

at

all.

In

terms

of

actual

income

earned

per

quarter

(every

three

months),

many

of

the

respondents

(21%)

earn

no

income.

These

include

students,

apprentices,

some

artisans

and

the

unemployed.

More

than

two-thirds

of

these

respondents

that

earn

no

income

are

from

Anambra

state.

Furthermore,

13.5%

of

the

respondents

earn

below

N30,000

per

quarter,

and

only

8.6%

earn

above

N131,000

per

quarter.

This

shows

that

income

status

of

individuals

within

the

area

of

study

is

generally

low.

The

mean

income

per

quarter

of

the

respondents

is

about

N59,033

with

a

standard

deviation

of

N45,933.

The

median

income

stood

at

about

N55,378.

(c)

Research

Question

1:

What

types

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

programmes

are

available

to

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states?

Data

relevant

to

the

research

question

are

presented

in

Tables

4

and

5

below.

Table

4:

Distribution

of

Respondents

by

their

opinion

on

whether

Social

and

Economic

Rehabilitation

is

a

component

of

Leprosy

Control

in

their

Area.

Source:

Field

Survey,

2010.

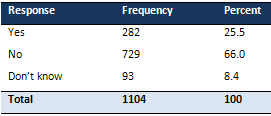

Table

4

shows

that

66%

of

the

respondents

stated

that

there

was

no

SER

component

of

leprosy

control

in

their

area.

Only

25.5%

of

the

respondents

acknowledged

existence

of

any

form

of

SER

activities.

However,

more

respondents

from

Ebonyi

state

(75.3%)

were

of

the

view

that

SER

was

not

a

component

of

leprosy

control

in

their

state

as

against

56.6%

who

had

a

similar

opinion

at

Anambra

state.

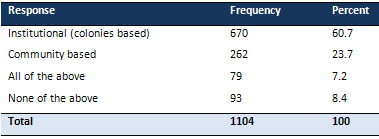

Also,

most

of

the

respondents

(60.7%)

identified

the

core

rehabilitation

strategy

as

institutional

or

colony

based

(see

Table

5

below).

This

suggests

that

the

current

thrust

of

World

Health

Organization

(WHO)

towards

Community

Based

Rehabilitation

(CBR)

is

yet

to

make

an

appreciable

impact

in

the

two

states.

Table

5:

Distribution

of

Respondents

by

their

opinion

on

Rehabilitation

Strategy

adopted

by

Leprosy

Control

Programme

Source:

Field

Survey,

2010.

The

specific

SER

activities

provided

or

available

to

patients

were

also

identified.

They

included

resettlement

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

colonies

which

ranked

tops

with

36.7%

of

responses.

Others

were

public

re-orientation

(17.3%),

vocational

/

occupational

training

(12.6%),

and

financial

support

to

set-up

small

businesses

(10.9%).

Furthermore,

approximately

half

of

the

respondents

(49.5%)

were

of

the

view

that

government,

NGOs,

companies,

philanthropists

and

faith

based

organizations

do

not

provide

support

for

SER

activities.

Only

about

14.9%

and

11.1%

of

the

respondents

acknowledged

NGO

and

government

support

for

SER

activities

as

part

of

leprosy.

Similarly,

most

of

the

respondents

(79.0%)

were

also

of

the

opinion

that

vocational

training

was

not

provided

to

leprosy

patients.

In

a

similar

vein,

most

of

the

respondents

(78.8%)

submitted

that

vocational

training

in

the

areas

of

carpentry;

shoe

making,

tailoring,

weaving

and

soap

making

were

not

provided

as

part

of

leprosy

control.

Many

of

the

respondents

(68.4%)

equally

stated

that

there

were

no

community

based

supportive

activities

aimed

at

rehabilitation

of

patients

and

stigma

reduction.

These

responses

reveal

the

lapses

of

the

control

programme

in

the

two

states

in

the

area

of

SER

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy.

The

high

negative

responses

to

SER

variables

were

however

not

fully

corroborated

by

IDI

participants.

More

than

half

of

the

IDI

participants,

particularly

health

workers

enumerated

efforts

at

rehabilitation

of

patients

but

accepted

that

a

lot

still

needs

to

be

done.

An

IDI

respondent

from

Anambra

state

reported

thus-

There

is

a

Community

Based

Rehabilitation

(CBR)

Committee

in

Anambra

state.

The

German

Leprosy

Relief

Association

(GLRA)

pays

about

12

persons

affected

by

leprosy

a

monthly

welfare

support

of

N2000.

Two

(2)

dependants

are

also

currently

benefiting

from

educational

support

from

GLRA.

The

respondent

also

recounted

that

financial

support

(loan)

to

the

tune

of

N10,000

for

trading

or

farming

was

provided

in

the

past

but

regretted

that

patients

did

not

repay

such

loans

to

enable

others

to

benefit.

On

their

part,

male

and

female

FGD

participants

at

Mile

4

Hospital

Abakaliki

recounted

promises

made

toward

their

social

and

economic

rehabilitation.

They

however

maintained

that

such

promises

are

yet

to

materialize.

Male

and

female

FGD

participants

at

Fr

Damian

TB

and

Leprosy

Hospital,

Nnewi/Amichi

in

Anambra

state

also

decried

the

absence

of

SER

programme

for

them.

They

maintained

that

they

depend

on

donations

of

people

of

goodwill

to

subsist.

(d)

Research

Question

2:

What

are

the

perceived

outcomes

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states?

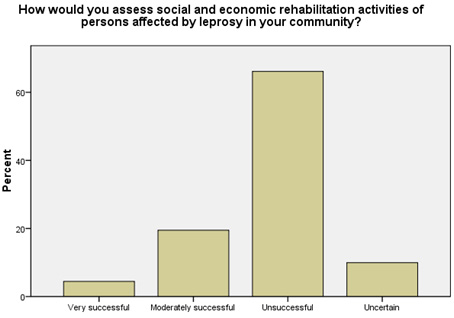

Data

relevant

to

the

research

question

are

reflected

in

the

bar

chart

(Figure

2)

and

Table

6

below.

Figure

2:

Respondents

Assessment

of

Social

and

Economic

Rehabilitation

(SER)

Activities

of

Persons

Affected

by

Leprosy

in

their

Community

The

chart

above

shows

that

most

of

the

respondents

(66.1%)

assessed

SER

component

of

the

leprosy

control

programme

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states

as

unsuccessful.

This

suggests

high

neglect

of

SER

activities

in

leprosy

control

in

the

area.

However,

more

respondents

from

Ebonyi

state

(88%)

subscribed

to

the

opinion

that

SER

was

unsuccessful

as

against

44.1%

from

Anambra

state

who

shared

similar

views.

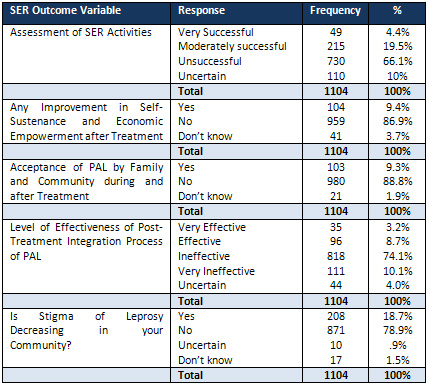

Table

6

below

summarizes

other

findings

on

perception

of

outcome

of

SER

activities.

Again,

the

table

shows

high

negative

responses

to

five

SER

outcome

variables

examined.

The

situation

points

to

the

magnitude

of

unmet

expectations

of

respondents

in

the

area

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

of

victims

of

leprosy.

Table

6:

Distribution

of

Respondents

by

their

Assessment

of

Outcomes

of

SER

Activities

in

Leprosy

Control

Source:

Field

Survey

2010.

The

FGD

results

agree

to

a

large

extent

with

the

above

table

over

poor

SER

outcomes.

The

opinion

of

a

female

FGD

participant

at

Fr

Damian

TB

and

Leprosy

Hospital,

Nnewi

summarizes

FGD

data

on

SER

outcome

in

both

states

is

as

follows

-'We

have

not

benefited

anything

except

free

drugs.

Others

are

but

promises.

I

look

forward

to

when

I

shall

not

be

called

all

sorts

of

names

and

be

truly

accepted

and

seen

as

a

human

being

in

my

community;

when

my

ulcer

and

deformed

fingers

are

disregarded

and

I

could

shop

with

money

earned

from

my

work

and

not

from

begging.

I

beg

out

of

frustration.

I

dislike

it'.

On

their

part,

many

IDI

participants

spoke

of

some

limited

level

of

success

in

SER

activities.

An

IDI

respondent

from

World

Health

Organization's

(WHO)

Zonal

Office

at

Enugu

clarified

as

follows-

'WHO

has

no

direct

SER

programme

for

persons

affected

by

leprosy.

However,

she

(WHO)

collaborates

with

partners

to

provide

cash

stipends,

vocational

training

and

prosthesis'.

The

respondent

however

noted

that

funding

for

SER

is

low,

and

that

SER

has

not

made

much

impact

in

leprosy

control

due

to

incomprehensive

data

base

on

patients'

needs.

Above

all,

the

respondent

lamented

that

many

leprosy

patients

were

already

disadvantaged

before

starting

treatment

and

SER

cannot

reverse

their

situation.

The

negative

perception

of

SER

outcome

cannot

be

totally

divorced

from

impediments

posed

by

limited

funds

and

poor

capacity

of

health

workers.

Late

commencement

of

treatment

and

its

associated

lifelong

disabilities

(present

even

after

completing

treatment)

cast

further

doubts

about

any

serious

plan

for

prevention

of

disabilities

(POD).

POD

which

is

a

key

component

of

SER

appears

to

be

weak

in

the

two

states.

In

the

context

of

weak

POD,

the

public

opinion

is

that

nothing

has

improved

as

long

as

disabilities

remain

with

patients.

The

situation

is

compounded

by

the

absence

of

corrective

surgery

facilities

for

persons

affected

by

leprosy

at

the

leprosy

clinics.

The

researcher

also

recognizes

that

weak

rehabilitation

plan

may

have

contributed

to

the

emergence

of

co-operatives

involving

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

their

attempt

to

help

themselves.

More

than

two-thirds

of

the

respondents

(70.9%)

acknowledged

the

existence

of

such

co-operatives

which

serve

as

coping

mechanisms

to

life

challenges

posed

by

leprosy.

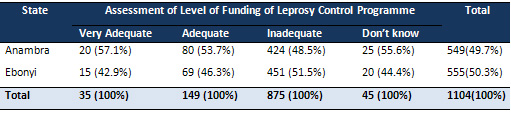

(d)

Research

Question

3:

How

do

people

of

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

States

of

Southeast

Nigeria

perceive

the

level

of

funding

for

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

in

their

area

in

terms

of

its

adequacy?

Table

7:

Distribution

of

Respondents

according

to

State

of

Origin

and

their

Assessment

of

Level

of

Funding

for

Leprosy

Control

Programme

X2

=

2.883,

df

=

3,

p

=

.410

From

Table

7

it

could

be

seen

that

there

is

no

significant

difference

in

the

mode

of

assessment

/

perception

of

funding

for

leprosy

control

activities

across

the

two

states.

Almost

an

equal

number

of

respondents

from

both

states

saw

funding

for

leprosy

control

as

inadequate.

This

suggests

that

funding

problem

remains

a

common

handicap

to

leprosy

control

in

both

states.

From

the

analysis

of

field

data,

it

was

observed

that

leprosy

was

considered

a

serious

skin

related

health

problem

in

the

area

studied.

This

is

consistent

with

findings

in

a

previous

study

by

Nicholls

(2000).

The

medical

and

social

problems

associated

with

leprosy

have

also

been

well

documented

by

scholars

(see

Federal

Ministry

of

Health,

FMOH

1997;

Sofola

1999,

Ogbeiwi

2005,

Rafferty

2005

etc).

The

fact

that

there

was

very

poor

performance

of

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

(SER)

component

of

leprosy

control

in

the

two

states

was

a

major

finding.

This

area

is

certainly

the

weakest

aspect

of

leprosy

control

in

the

two

states.

Most

study

participants

responded

negatively

to

the

issue

of

availability

of

SER

activities

and

to

five

SER

outcome

variables

that

were

examined.

Such

poor

performance

of

SER

component

is

a

departure

from

the

submissions

of

both

Smith

(2000)

and

WHO

(1999).

They

have

held

that

SER

should

actually

be

a

priority

in

leprosy

control

projects.

The

respondents

in

this

study

were

of

the

opinion

that

vocational

training,

stigma

reduction,

economic

empowerment

and

acceptance

of

PAL

by

community

have

all

failed

to

materialize

as

envisaged.

The

finding

of

this

study

with

respect

to

SER

is

also

totally

at

variance

with

those

of

Nash

(2001)

who

held

that

SER

had

attained

significant

levels

of

success

in

Nigeria

or

that

patients

had

fitted

into

new

economic

roles

that

won

them

social

acceptance

and

respect.

The

disconnect

in

findings

between

the

present

study

and

that

of

Nash

(2001)

could

be

explained

by

the

time

lag

between

the

two

studies

and

the

fact

that

Nash

focused

on

Northern

Nigeria

while

the

present

study

was

located

at

the

Southeast

zone.

Above

all,

institutional

(colony

based)

rather

than

community

based

rehabilitation

strategies

were

still

being

practiced

with

limited

results.

Factors

accountable

for

the

deplorable

SER

status-quo

include

belief

systems,

low

public

enlightenment,

poor

logistics,

low

knowledge,

lack

of

funds,

inadequate

and

non-enthusiastic

health

staff.

There

was

also

no

strategy

in

place

to

ensure

that

rehabilitation

takes

on

a

multi-sectoral

approach

best

suited

for

its

operations.

The

situation

was

further

compounded

by

the

fact

that

the

Social

Welfare

Department

and

other

important

agencies

were,

in

the

opinion

of

respondents,

operating

at

a

distance

away

from

SER

activities

in

leprosy

control.

The

synergy

and

collaboration

that

ought

to

characterise

their

relationship

was

nonexistent.

These

observations

on

the

state

of

rehabilitation

of

PAL

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states

could

be

accountable

for

the

conclusion

drawn

by

Nigeria

Television

Authority

(NTA,

2011)

to

the

effect

that

rehabilitation

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

is

largely

unaddressed

in

Nigeria.

The

role

of

funding

in

leprosy

control

has

been

strongly

emphasized

by

Anyam

(2001)

and

Osakwe

(2004).

This

study

affirmed

their

contentions

but

also

revealed

that

most

respondents

actually

saw

the

level

of

funding

for

leprosy

control

in

Anambra

and

Ebonyi

states,

especially

as

applicable

to

SER,

as

inadequate.

Many

IDI

respondents

(health

workers)

reported

poor

budgetary

allocation

to

leprosy

control.

Also,

leprosy

patients

who

were

participants

in

the

FGD

sessions

recounted

severe

financial

difficulties

which

they

experienced.

These

observations

justify

the

position

of

the

political

economy

framework

that

government

often

channel

resources

to

maintenance

of

production

to

the

neglect

of

core

social

goal

of

securing

and

improving

health.

A

properly

funded

leprosy

control

programme

will

be

responsive

to

both

medical

and

economic

needs

of

patients.

| CONCLUSIONS

AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

|

Based

on

the

findings

from

the

present

study,

the

following

recommendations

can

be

made:

1.

There

is

immense

need

to

improve

the

level

of

community

involvement,

ownership

and

participation

in

the

programme

which

is

currently

very

low.

The

involvement

of

community

leaders

is

a

laudable

step

in

this

direction.

In

addition,

the

role

of

social

groups

like

age-grades,

women

groups,

clubs

and

faith-based

associations

will

positively

affect

decisions

toward

ameliorating

the

effects

of

socio-cultural

factors

on

leprosy

control

programme.

With

the

support

and

participation

of

the

community,

socio-cultural

practices

and

beliefs

that

negatively

affect

leprosy

control

should

be

abolished

/prohibited.

2.

There

is

need

for

a

holistic

leprosy

control

programme

which

should

include

crucial

components

like

social

and

economic

rehabilitation

and

reintegration

of

persons

affected

by

leprosy

into

their

communities.

Such

a

holistic

package

will

ensure

that

persons

affected

by

leprosy

are

properly

treated.

It

will

also

ensure

that

they

are

economically

empowered

and

remained

socio-politically

relevant

despite

their

disease

experience.

3.

Existing

legislations

should

be

enforced

and

new

ones

enacted

to

adequately

protect

persons

affected

by

leprosy

from

all

forms

of

stigmatization,

discrimination,

and

violations

of

their

fundamental

human

rights.

Such

measure

of

protection

will

encourage

them

to

live

normal

lives

devoid

of

social

seclusion

or

withdrawal

and

to

positively

respond

to

their

problem.

4.

There

is

immense

need

for

inter-agency

collaboration

to

meet

the

goals

of

leprosy

control.

The

programme

should

liaise

with

National

Poverty

Alleviation/

Eradication

Programme

and

the

Social

Welfare

Department

etc

to

address

issues

of

poverty,

welfare

and

social

integration

as

they

affect

leprosy

patients.

The

Ministry

of

Education

at

the

three

tiers

of

government

should

also

be

involved

with

a

view

to

including

leprosy

as

a

subject

of

study

in

the

curricula

of

schools.

This

is

sequel

to

the

finding

that

formal

education

generally

has

positive

impact

on

leprosy

control.

5.

Government

at

all

levels

should

demonstrate

strong

political

will

and

commitment

toward

leprosy

control.

This

should

be

done

through

adequate

funding,

prompt

release

of

budgeted

sums,

provision

of

infrastructure,

logistics,

training

and

motivation

of

leprosy

control

staff

through

prompt

payment

of

entitlement

and

allowances.

6.

There

should

also

be

a

synergy

between

donor

agencies,

non-governmental

organizations,

development

partners

and

government

departments

involved

in

leprosy

control.

All

channels

of

energy

leakage,

wasteful

duplication

of

functions

and

confrontations

should

be

blocked.

7.

Because

of

observed

negative

impact

of

socio-cultural

factors

like

belief

system

on

leprosy

control,

there

is

immense

need

to

enhance

the

capacity

of

health

workers

to

understand

socio-cultural

factors

related

to

leprosy.

This

could

be

achieved

through

on

the

job

training

to

equip

them

about

behaviour

change

techniques.

Furthermore,

social

scientists

that

are

likely

to

better

understand

and

plan

interventions

against

such

socio-cultural

dimensions

should

be

part

of

leprosy

control

teams

in

the

spirit

of

inter-disciplinary

co-operation

and

better

results.

Adagba

.K.

(2011).