|

The effectiveness of

life skills training on happiness, mental health,

and marital satisfaction in wives of Iran-Iraq

war veterans

Kamal Solati

Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry,

Social Determinants of Health Research Center,

Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences,

Shahrekord, Iran

Correspondence:

Department of Psychiatry,

Shahrekord University of Medical Sciences, Rahmatiyeh,

Shahrekord, Iran,

Tel.: +98-3833338891,

Email: kamal_solati@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Background:

Injury due to war or accidents causes

numerous mental, physical, and social

adverse effects on affected individuals

and their family.

Aims: This

study was conducted to determine the effectiveness

of life skills training on happiness,

mental health, and marital satisfaction

in wives of Iran-Iraq war veterans.

Methods and

Material: In this semi experimental,

controlled study with pretest-posttest,

102 veterans in Shahrekord, southwest

Iran were randomly assigned to two groups,

intervention and control, after they filled

out a written consent form. The intervention

group alone received training on four

domains of life skills, coping with stress,

problem solving, decision-making, and

communication skills, for eight weeks.

Oxford Happiness Questionnaire, General

Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), and ENRICH

Marital Satisfaction Scale were administered

at three steps, before intervention, immediately

after intervention, and six months after

intervention (as follow-up). The data

were analyzed by analysis of covariance

in SPSS 23.

Results:

The mean scores of happiness and mental

health indicated a significant difference

between the two groups at posttest (P<001).

But in follow-up, the difference was significant

for neither of the variables (P>0.05).

Mean scores of marital satisfaction exhibited

significant difference at both posttest

(P<001) and follow-up (P=0.001) between

the two groups.

Conclusion:

Life skills training for veterans’

wives can help them promote their mental,

physical health, and marital satisfaction,

but the findings on follow-up indicate

that this effect is not lasting. Therefore,

life skills training should be done continuously

particularly to promote mental health

and happiness.

Key words: Mental

Health, Happiness, Life, War veterans

|

World Health Organization (WHO), with UNICEF

coordination, has launched Life Skills Training

Program as a primary prevention and comprehensive

project of health promotion in children and

adolescents. WHO defines life skills as “the

ability to behave adaptively and positively

to be capable of coping with life necessities

and challenges”. Furthermore, WHO has introduced

ten skills as main life skills including decision-making,

problem solving, creative thinking, critical

thinking, effective communication skills, interpersonal

relationships skills, self-awareness, empathy,

and coping with stress and emotions (1). Chronic

diseases can cause negative effects on quality

of life and various aspects of health (2-9).

Making attempts to understand and assist the

psychiatric victims of wars and accidents requires

psychiatric and psychological interventions

to promote and maintain their health (10). Studies

have shown that posttraumatic stress disorder

(PTSD) affects not only the patients but also

their family function such as family cohesion,

parents’ satisfaction, relationship with

spouse, spouse self-identification, and children’s

emotional and functional safety (11-14). The

veterans of Iran-Iraq War suffer from different

complications and trauma, decrease in libido,

offensive disorder, conflict, and psychotic

symptoms (15, 16) which can influence the happiness,

mental health, and marital satisfaction in them

and their families.

Happiness is a kind of feeling positive. Happiness

means increase in positive feelings, high life

satisfaction, and relief of negative feelings

(17). Experiences of happiness depend on self-concept.

People with low self-esteem and self-worth are

often unhappy (18). Happiness rate is likely

to increase through training in the ten life

skills.

Mental health is a state of well-being in which

people realize their potential, cope with routine

life stresses, can function usefully and efficiently,

and help community (WHO, 2005), and marital

satisfaction refers to individual experiences

of marriage that are only measured by response

to the degree of the pleasure derived from marriage

(19). Studies have indicated that dissatisfaction

with married life is associated with development

of depression (20, 21), and marriage compatibility

is lower in the wives of the veterans with PTSD.

Moreover, marriage compatibility was considerably

lower in the couples both with PTSD than those

with only the veteran suffering from PTSD (22).

A study has shown that the chemical veterans

of the Iran-Iraq War are dependent on others,

particularly their wives, and cannot do even

their daily activities and hence are under stress

(23).

Many studies have been conducted on the effect

of life skills training on different populations

with different problems indicating the efficiency

of this method. The effect of life skills training

on relief of stress, prevention of high risk

sexual behaviors, and abuse of alcohol and substances

in adolescents has been reported (24-27). Codony

et al found that life skills training for adolescents

caused increase in self-confidence, life satisfaction,

and improvement of problem solving (28). In

a study in Mexico, life skills training for

girls led to increased self-efficacy and self-esteem

after training (29).

The soldiers with PTSD have been reported to

be involved in family aggression more frequently

than those without PTSD (30). The studies have

shown that the families of the war-afflicted

people suffer from many problems requiring therapeutic

interventions. Accordingly, a significant decrease

in severe psychiatric disorders was seen in

the war-afflicted families following psychological

training (31).

The studies of the people injured due to war

or trauma (psychiatric and physical injuries)

and their families have indicated that it causes

not only psychological, physical, and social

impacts on the injured people but also affects

their family members, particularly wives, indirectly,

and is associated with many adverse effects

in different domains, including marital, family,

and interpersonal, as well as psychiatric disorders,

depression, and anxiety. Previous studies have

mainly described the problems in these families

and less frequently investigated the educative

and therapeutic interventions.

The training on managing anger and stress,

decision making, problem solving, and communication

skills delivered to the relatives of this subpopulation

of the community is likely to contribute to

both prevention and resolution of the current

problems.

Therefore, the present study was conducted

to investigate and follow up the effect of life

skills training on happiness, mental health,

and marital satisfaction in the veterans’

wives in southwest Iran. The findings of this

study can help plan for mental health promotion

in the veterans’ wives to resolve the marital

and familial problems and increase the rate

of life satisfaction in these families.

In this controlled, quasi-experimental study

with pretest and posttest, the study population

consisted of the wives of all veterans with

25-70% physical and psychiatric injuries due

to war in Shahrekord, southwest Iran. Sampling

was random and convenience. Because the participants

were selected from the Martyrs Foundation, primary

sampling was convenience. Then, as the list

of veterans with 25-70% injuries was provided,

102 veterans were selected according to convenience

sampling and then their wives were enrolled

in the study. Regarding first type error=0.05,

power=0.80, happiness mean score of 13.20 in

a previous study (32), and 87.2 difference in

effect size (delta=2.87), 48 people were assigned

to each group. To further the rigor of the study

and deal with possible attrition, 51 people

were included in each group and totally 102

people were investigated. The participants were

randomly assigned to two 51- people groups,

case and control. The research protocol was

registered as 89-5-10 by the ethics committee

of the university.

The participants in the intervention group attended

eight sessions of life skills training on four

domains, stress management, problem solving,

decision making, and communication skills. The

control group underwent no treatment.

The protocol of life skills training

The intervention group received life skills

training on four domains consisting of stress

management, problem solving, decision making,

and communication skills within eight sessions,

and the control group underwent no intervention.

To increase the efficiency of training, the

intervention group was subdivided into three

groups of 17 each and the training was conducted

within one 2-hour session per week separately

for each subgroup.

In each of these sessions, a skill was discussed

and the homework, including special forms appropriate

for the session content, was developed prior

to that session and assigned to be done at home,

in addition to the assignments within sessions.

This training was conducted by a trained and

experienced clinical psychologist. At the beginning

of any session, the previous session was examined

and assessed and then the new subject was introduced.

The subjects for stress management were an introduction

to stress, positive and negative stress, stress

impacts and consequences (physiological, psychological,

and behavioural), different methods of coping

with the problems specific to the veterans’

families, and assigning homework.

For problem solving skill, the sessions included

introduction to problem, steps of problem solving,

the ways of gathering data to arrive at solutions,

detecting different solutions in coping with

life problems and adopting the best one, the

ways of clear thinking and problem solving in

critical conditions, regulation and control

and precision, reconciliation to resolve conflicts,

the effect of problem solving on solving the

daily problems of the veterans’ families,

and assigning homework.

For decision making skill, the sessions included

the introduction to decision making, the significance

of decision making in life, steps of decision

making, gathering data as much as possible in

decision making, decision making precisely based

on the situations, planning for life, acceptance

of decision making consequences, and assigning

homework.

For communication skills, the sessions included

the introduction to communication, definition

of communication and associated factors, the

process of establishing communication, being

a good listener and the required skills for

listening efficiently, verbal and nonverbal

communication (features), effective methods

of communicating with others, assertiveness,

understanding others’ feelings, respect

for others’ ideas, the methods of saying

no to insensible requests, and assigning homework.

The study was conducted at three steps, i.e.

pretest, posttest after two months of life skills

training, and follow-up (six months after the

last intervention). The two groups were assessed

at each step of the study by administration

of the research instruments. Follow-up was considered

to assess the stability of the training in the

intervention group.

Methods of data collection:

The data were gathered by three questionnaires

as follows:

1. Oxford Happiness Questionnaire

This questionnaire, developed by Argyle et al,

consists of 29 four-choice items. Each item

is aimed to judge the happiness level of respondents.

Argyle et al (1989) reported the reliability

of this questionnaire 0.90 by Cronbach’s

alpha and 0.78 by test-retest with a seven-week

interval (33). This questionnaire was translated

into Persian by Alipoor and Noorbala and its

reliability has been reported 0.98 by Cronbach’s

alpha, 0.92 by split-half reliability, and 0.79

by test-retest with a three-week interval. Furthermore,

the face validity of the questionnaire has already

been confirmed (34).

2. General Health Questionaire-28

This 28-item questionnaire investigates the

illness, medical diseases, and general and mental

health within the past month with minimal and

maximal score of 0 and 56, respectively. This

questionnaire was developed by Goldberg in 1972

and has been translated into 38 languages and

is being administered in 70 countries. Its subscales

are physical symptoms, anxiety symptoms and

sleep disorder, social functioning, and depression

symptoms. High reliability and reliability have

been reported for different versions of this

questionnaire (35-37). Williams et al in a study

in England reported the reliability of this

questionnaire as approximately 80% (37). Furthermore,

its reliability has been confirmed for an Iranian

population with Cronbach’s alpha 0.97 (38).

3. ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale:

The original version of this scale consists

of 115 items and 12 subscales. Given the large

number of the scale’s items and the participants’

tiredness, a shortened, 47-item version of the

original scale was developed. The subscales

of this scale were personality issues, marital

relationship, resolution of conflict, financial

management, leisure activities, sexual intercourse,

marriage and children, relatives and friends,

and religious orientation. The replies to the

scale’s items were scored by a five-point

Likert scale consisting of severely dissatisfied,

moderately dissatisfied, very satisfied, and

extraordinarily satisfied. The reliability and

validity of this Scale have already been confirmed

(39).

The demographic data of the participants (marital

status, education level, age, place of residence,

occupation, disability percentage of the veterans,

and disability type) were recorded in a separate

checklist. To study the association of happiness

in the veterans wives, the mean (SD) scores

of the two groups at three steps of the study

were compared and the effect of difference on

happiness was investigated in the intervention

group by analysis of covariance. The data were

analyzed by SPSSv23.

The

mean

age

of

the

participants

was

40.61±5.49

years.

97.06%

of

the

participants

had

at

least

elementary

education.

The

highest

frequency

of

education

level

was

obtained

for

guidance

education

completion.

63.7%

of

the

participants

were

living

in

cities

and

the

rest

in

villages.

90.2%

were

housewives

and

only

9.8%

were

employed

(mainly

civil

servants).

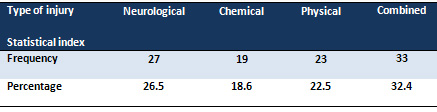

Regarding

the

types

of

veterans’

injuries,

26.5%

were

neurologically

injured,

18.6%

were

injured

by

chemical

weapons,

22.5%

were

physically

injured,

and

32.4%

had

combined

injury.

85%

of

the

veterans

were

25-40%

disabled

(Table

1).

Table

1:

The

types

of

the

injuries

of

participants’

spouses

Table

2

shows

both

frequency

and

percentage

of

injuries

of

the

participants’

spouses.

As

shown,

the

percentage

of

the

injuries

of

most

participants’

spouses

was

40%

and

the

percentage

of

the

least

number

of

participants’

injuries

was

45%-55%.

Click

here

for

Table

2:

The

frequency

and

percentage

of

injuries

of

the

participants’

spouses

The

mean

score

of

happiness

in

the

intervention

group

(49.39)

increased

more

markedly

than

the

control

group

(36.98)

at

follow-up

(Table

3).

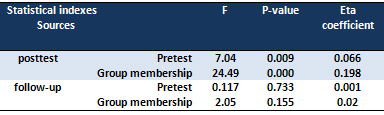

Furthermore,

Table

4

indicates

a

significant

difference

was

seen

in

happiness

mean

scores

between

the

two

groups

at

posttest

so

that

the

mean

difference

was

not

significant

after

controlling

for

pretest

scores

as

covariate.

Click

here

for

Table

3:

Statistical

indexes

of

crude

scores

of

happiness

in

participants

of

two

groups

Statistical

power

(0.998)

indicated

that

the

sample

size

was

adequately

large.

Therefore,

the

difference

between

the

two

groups

at

posttest

was

confirmed

and

life

skills

training

resulted

in

increased

happiness

in

the

veterans’

wives

at

posttest,

but

no

significant

difference

was

seen

in

the

mean

scores

of

happiness

between

the

two

groups

at

follow-up,

so

that

after

controlling

for

pretest

scores,

the

mean

difference

was

not

derived

as

significant

(Table

2).

Therefore,

life

skills

training

had

no

stable

effect

on

happiness

and

the

happiness

rate

decreased

over

time

in

the

participants.

Table

4:

Results

of

analysis

of

covariance

for

effect

of

life

skills

training

on

happiness

in

participants

at

posttest

and

follow-up

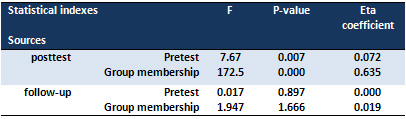

The

mean

score

of

mental

health

decreased

markedly

at

follow-up

in

the

intervention

group

(22.96).

This

means

that

after

life

skill

training,

mental

health

in

the

intervention

group

improved

but

did

not

change

in

the

control

group

(37.57)

(Table

5).

Table

6

indicates

that

there

is

a

significant

difference

in

the

mean

scores

of

mental

health

between

the

two

groups

at

posttest.

Eta

coefficient

(0.635)

indicated

that

63%

of

the

observed

difference

was

explained

by

life

skills

training.

Therefore,

life

skills

training

led

to

improvement

of

mental

health

in

the

veterans’

wives

at

posttest.

The

mean

scores

of

mental

health

were

not

significantly

different

between

the

two

groups

at

follow-up

(Table

7).

In

other

words,

life

skills

training

had

no

stable

effect

on

mental

health

in

the

veterans’

wives

and

the

mean

score

of

the

two

groups

was

approximately

equal

six

months

after

the

last

intervention.

Click

here

for

Table

5:

Statistical

indexes

of

crude

scores

of

mental

health

in

the

participants

of

two

groups

Table

6:

Results

of

analysis

of

covariance

for

effect

of

life

skills

training

on

mental

health

in

participants

at

posttest

and

follow-up

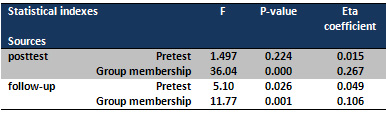

The

mean

scores

of

marital

satisfaction

in

the

intervention

group

at

pretest,

posttest,

and

follow-up

(135.68,

176.77,

and

159.20,

respectively)

increased

markedly

compared

to

the

control

group

(136.43,

141.05,

and

140.70,

respectively).

This

indicates

increase

in

marital

satisfaction

in

the

participants

(Table

7).

Click

here

for

Table

7:

Statistical

indexes

of

crude

scores

of

marital

satisfaction

in

the

participants

of

two

groups

Table

8

indicates

that

a

significant

difference

is

seen

in

mean

score

of

marital

satisfaction

between

the

two

groups

at

posttest.

In

other

words,

life

skills

training

led

to

increased

marital

satisfaction

in

the

veterans’

wives

in

the

intervention

group

at

posttest

but

this

difference

was

not

notable

in

the

control

group.

Furthermore,

a

significant

difference

in

mean

score

of

marital

satisfaction

was

seen

between

the

two

groups

at

follow-up.

Therefore,

the

significant

difference

in

marital

satisfaction

between

the

two

groups

was

confirmed

at

follow-up,

and

life

skills

training

had

a

stable

effect

on

marital

satisfaction

in

the

veterans’

wives.

Table

8:

Results

of

analysis

of

covariance

for

effect

of

life

skills

training

on

marital

satisfaction

in

participants

at

posttest

and

follow-up

Obviously,

the

veterans’

families

are

affected

with

certain

psychological

and

marriage

incompatibility-associated

problems

and

therefore

their

quality

of

life

is

affected

(32).

Meanwhile,

veterans’

wives

are

likely

to

experience

greater

levels

of

stress

with

mental

health

and

life

satisfaction

being

at

higher

risk

than

other

family

members

(33).

These

findings

indicate

that

these

problems

have

many

negative

effects

on

the

veterans’

family

members

particularly

their

wives,

and

life

skills

training

can

greatly

enhance

the

methods

of

coping

with

these

problems

and

their

happiness.

The

present

study

indicated

that

the

life

skills

training

on

four

domains

of

coping

with

stress,

decision

making,

problem

solving,

and

interpersonal

and

social

relationships

could

result

in

the

relief

of

the

problems

in

these

families.

More

clearly,

life

skills

training

had

no

long-term

effect

on

happiness

in

the

veterans’

wives.

Carroll

et

al

study

demonstrated

that

training

life

skills

can

promote

coping

skills

in

the

families

of

military

staff

to

deal

with

adverse

and

unexpected

circumstances

(34).

Life

skills

training

like

mental

health

and

resilience

intervention

for

military

staff’s

wives

can

reduce

negative

mental

health

symptoms,

enhance

resiliency,

and

improve

coping

skills

(40).

Elliott

et

al’s

study

found

that

training

of

problem

solving

as

a

life

skill

was

effective

in

relieving

depression

in

the

family

caregivers

of

disabled

women

(41).

The

wives

of

war-afflicted

people

were

mainly

responsible

for

both

caring

for

the

veterans

and

the

related

problems

and

looking

after

children.

This

leads

to

heavy

psychological

and

physical

consequences

in

people

under

such

circumstances.

Therefore,

the

treatment

of

these

people

is

far

more

complex.

Naturally,

the

problems

in

these

families

are

much

more

complicated,

representing

that

they

require

continuous

training

to

cope

with

the

problems,

and

no

training

and

failure

to

support

them

leads

to

incidence

and

exacerbation

of

the

problems.

In

the

present

study,

life

skills

training

caused

promotion

of

mental

health

in

the

veterans’

wives.

Similarly,

Weines

et

al

indicated

that

psychological

education

of

Kosovo

War-afflicted

families

suffering

from

severe

psychiatric

disorders

led

to

remarkable

relief

of

symptoms

and

improvement

of

mental

health

(31).

Consistent

with

the

present

study,

Layne

et

al

reported

a

58%

decrease

in

PTSD

and

20%

decrease

in

depression

after

interventions

(42).

However,

in

the

present

study,

no

significant

difference

was

observed

in

the

mean

score

of

mental

health

between

the

two

groups

at

follow-up.

In

other

words,

life

skills

training

had

no

continuous

and

long-term

effect

in

treating

symptoms

and

promoting

mental

health

in

the

veterans’

wives,

which

is

partially

inconsistent

with

the

study

of

Layne

et

al

that

reported

an

81%

decrease

in

PTSD

symptoms

and

61%

decrease

in

depression

symptoms

four

months

after

the

last

intervention

(at

follow-up)

in

war-afflicted

adolescents

(42).

As

previously

argued,

this

inconsistency

could

be

due

to

differences

in

the

participants’

experiences.

The

results

of

marital

satisfaction

indicated

that

life

skills

training

led

to

a

stable

increase

in

marital

satisfaction

in

the

veterans’

wives.

The

findings

of

the

present

study

are

consistent

with

the

study

of

Hojjat

et

al

of

PTSD

effect

on

the

spouses

of

veterans

with

PTSD.

They

conclude

that

education

of

coping

with

stress

was

effective

in

increasing

the

marital

satisfaction

in

these

women

(43).

The

researchers

of

this

study

argued

that

the

symptoms

of

emotional

indifference

and

anger

should

be

especially

addressed

in

such

people

and

treatment

of

the

patients

with

PTSD

should

be

based

on

life

skills

training

and

support

for

family

(44).

The

present

study

can

demonstrate

that

the

families

of

military

staff

with

PTSD

suffer

from

some

problems

that

may

be

transferred

even

from

one

generation

to

another,

including

the

problems

related

to

intimacy

and

sociability,

marriage

incompatibility,

adaptive

communication

and

physical

aggressiveness,

disorders

of

interpersonal

skills,

and

marital

issues

(45-47).

The

life

skills

training

used

in

the

present

study

could

relieve

the

above

problems

and

strengthen

adaptation

to

life

circumstances,

and

lead

to

individual

and

interpersonal

improvement

and

increased

satisfaction

with

marriage

and

family

life

in

these

families.

Life

skills

training

could

lead

to

positive

effects

on

mental

and

physical

status

and

marital

satisfaction

in

veterans’

wives.

The

important

implication

of

the

present

study

was

that

life

skills

should

be

educated

continuously

for

veterans

and

their

families

because

the

participants

had

recurrent

symptoms

and

problems

in

the

follow-up.

Unfortunately,

veterans’

families

have

been

recently

abandoned

unaided

and

only

Counseling

Center

of

Martyr

Foundation

is

delivering

individual

and

voluntary

services

to

these

families.

In

contrast,

most

of

the

necessary

training

for

such

families

should

be

conducted

in

a

group,

continuously,

and

depending

on

the

type

of

disability.

This

issue

is

more

urgent

for

the

families

with

veterans

with

more

severe

disability

and

neurological

problems.

Further

studies

are

recommended

to

study

the

effect

of

psychological

interventions

on

veterans’

wives

and

other

family

members

depending

on

the

type

of

their

injuries.

Veterans

suffer

from

different

types

of

handicaps

and

therefore

their

families,

including

wives,

are

variously

affected.

For

example,

the

effects

on

the

family

of

a

veteran

with

PTSD

may

be

widely

different

from

those

on

the

family

of

a

veteran

with

a

handicap

from

shooting.

However,

we

decided

to

enroll

veterans

with

different

types

of

handicaps

to

have

an

adequate

sample

size.

Consequently,

the

findings

should

be

cautiously

interpreted

and

generalized.

Acknowledgements:

The

author

sincerely

thanks

all

people

who

cooperated

with

this

study.

1.

WHO.

Programme

on

mental

health,

Life

skills

education

in

schools.

Division

of

mental

health

and

prevention

of

substance

abuse.

1997;Geneva:1.

2.

Nikfarjam

M,

SolatiDehkordi

K,

Aghaei

A,

Rahimian

G.

Efficacy

of

hypnotherapy

in

conjunction

with

pharmacotherapy

and

pharmacotherapy

alone

on

the

quality

of

life

in

patients

with

irritable

bowel

syndrome.

Govaresh.

2013;18(3):149-56.

3.

Haghayegh

SA,

Neshatdoost

H,

Drossman

DA,

Asgari

K,

Soulati

SK,

Adibi

P.

Psychometric

Characteristics

of

the

Persian

Version

of

the

Irritable

Bowel

Syndrome

Quality

of

Life

Questionnaire

(P-IBS-QOL).

Pakistan

Journal

of

Medical

Sciences.

2012;8(2):312-7.

4.

Solati

K.

Effectiveness

of

cognitive-behavior

group

therapy,

psycho-education

family,

and

drug

therapy

in

reducing

and

preventing

recurrence

of

symptoms

in

patients

with

major

depressive

disorder.

Journal

of

Chemical

and

Pharmaceutical

Sciences.

2016;2(40.84):3.55.

5.

Asadi

Noghabi

AA,

Zandi

M,

Mehran

A,

Alavian

SM,

Dehkordi

AH.

The

Effect

of

Education

on

Quality

of

Life

in

Patients

under

Interferon

Therapy.

Hepatitis

Monthly.

2010:10(3):218-22.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC3269087.

6.

Solati

K,

Lo’Bat

Ja’Farzadeh

AH.

The

effect

of

stress

management

based

on

group

cognitive-behavioural

therapy

on

marital

satisfaction

in

infertile

women.

Journal

of

clinical

and

diagnostic

research:

2016;10(7):VC01.

7.

Solati

K.

The

Efficacy

of

Mindfulness-Based

Cognitive

Therapy

on

Resilience

among

the

Wives

of

Patients

with

Schizophrenia.

Journal

of

clinical

and

diagnostic

research:

2017;11(4):VC01.

8.

Dehkordi

AH,

Solati

K.

The

effects

of

cognitive

behavioral

therapy

and

drug

therapy

on

quality

of

life

and

symptoms

of

patients

with

irritable

bowel

syndrome.

Journal

of

advanced

pharmaceutical

technology

&

research.

2017;8(2):67.

9.

Solati

Dehkordy

K,

Adibi

P,

Sobhi

Gharamaleky

N.

Effects

of

relaxation

and

citalopram

on

severity

and

frequency

of

the

symptoms

of

irritable

bowel

syndrome

with

diarrhea

predominance.

Pakistan

Journal

of

Medical

Sciences.

2010;26(1):88-91.

Pakistan

Journal

of

Medical

Sciences.

2010;26(1):88-91.

10.

Elbogen

EB,

Fuller

S,

Johnson

SC,

Brooks

S,

Kinneer

P,

Calhoun

PS,

et

al.

Improving

risk

assessment

of

violence

among

military

veterans:

an

evidence-based

approach

for

clinical

decision-making.

Clinical

psychology

review.

2010

Aug;30(6):595-607.

PubMed

PMID:

20627387.

Pubmed

Central

PMCID:

2925261.

11.

Galovski

T,

Lyons

JA.

Psychological

sequelae

of

combat

violence:

A

review

of

the

impact

of

PTSD

on

the

veteran’s

family

and

possible

interventions.

Aggression

and

Violent

Behaviour.

2004;9(5):477–501.

12.

King

DW,

Taft

C,

King

LA,

Hammond

C,

Stone

ER.

Directionality

of

the

Association

Between

Social

Support

and

Posttraumatic

Stress

Disorder:

A

Longitudinal

Investigation.

Journal

of

applied

social

psychology.

2006;36(12):2980-92.

13.

Nichols

LO,

Martindale-Adams

J,

Graney

MJ,

Zuber

J,

Burns

R.

Easing

reintegration:

telephone

support

groups

for

spouses

of

returning

Iraq

and

Afghanistan

service

members.

Health

communication.

2013;28(8):767-77.

PubMed

PMID:

24134192.

14.

Renshaw

KD,

Rodrigues

CS,

Jones

DH.

Psychological

symptoms

and

marital

satisfaction

in

spouses

of

Operation

Iraqi

Freedom

veterans:

relationships

with

spouses’

perceptions

of

veterans’

experiences

and

symptoms.

Journal

of

family

psychology:

2008

Aug;22(4):586-94.

PubMed

PMID:

18729672.

15.

Ahmadi

K,

Ranjebar-Shayan

H,

Raiisi

F.

Sexual

dysfunction

and

marital

satisfaction

among

the

chemically

injured

veterans.

Indian

journal

of

urology.

2007

Oct;23(4):377-82.

PubMed

PMID:

19718292.

Pubmed

Central

PMCID:

2721568.

16.

Ahmadi

K,

Fathi-Ashtiani

A,

Zareir

A,

Arabnia

A,

Amiri

M.

Sexual

dysfunctions

and

marital

adjustment

in

veterans

with

PTSD.

Archives

of

Medical

Science.

2006;2(4):280-5.

17.

Lyubomirsky

S,

King

L,

Diener

E.

The

benefits

of

frequent

positive

affect:

does

happiness

lead

to

success?

Psychological

bulletin.

2005

Nov;131(6):803-55.

PubMed

PMID:

16351326.

18.

Lyubomirsky

S,

Tkach

C,

DiMatteo

MR.

What

are

the

differences

between

happiness

and

self-esteem.

Social

Indicators

Research.

2006;78(3):363-404.

19.

Kaplan

M,

Maddux

JE.

Goals

and

marital

satisfaction:

Perceived

support

for

personal

goals

and

collective

efficacy

for

collective

goals.

Journal

of

Social

and

Clinical

Psychology.

2002;21(2):157-64.

20.

Kim

GS,

Kim

B,

Moon

SS,

Park

CG,

Cho

YH.

Correlates

of

depressive

symptoms

in

married

immigrant

women

in

Korea.

Journal

of

transcultural

nursing

:

official

journal

of

the

Transcultural

Nursing

Society

/

Transcultural

Nursing

Society.

2013

Apr;24(2):153-61.

PubMed

PMID:

23341405.

21.

Miller

RB,

Mason

TM,

Canlas

JM,

Wang

D,

Nelson

DA,

Hart

CH.

Marital

satisfaction

and

depressive

symptoms

in

China.

Journal

of

family

psychology

:

JFP

:

journal

of

the

Division

of

Family

Psychology

of

the

American

Psychological

Association.

2013

Aug;27(4):677-82.

PubMed

PMID:

23834363.

22.

Klaric

M,

Franciskovic

T,

Stevanovic

A,

Petrov

B,

Jonovska

S,

Nemcic

Moro

I.

Marital

quality

and

relationship

satisfaction

in

war

veterans

and

their

wives

in

Bosnia

and

Herzegovina.

European

journal

of

psychotraumatology.

2011;2.

PubMed

PMID:

22893809.

Pubmed

Central

PMCID:

3402112.

23.

Afkar

AH,

Mahbobubi

M,

Neyakan

Shahri

M,

Mohammadi

M,

Jalilian

F,

Moradi

F.

Investigation

of

the

relationship

between

illogical

thoughts

and

dependence

on

others

and

marriage

compatibility

in

the

Iranian

Veterans

exposed

to

chemicals

in

Iran-Iraq

War.

Global

journal

of

health

science.

2014

Sep;6(5):38-45.

PubMed

PMID:

25168982.

24.

Sepulveda

AR,

Lopez

C,

Macdonald

P,

Treasure

J.

Feasibility

and

acceptability

of

DVD

and

telephone

coaching-based

skills

training

for

carers

of

people

with

an

eating

disorder.

The

International

journal

of

eating

disorders.

2008

May;41(4):318-25.

PubMed

PMID:

18176950.

25.

Magnani

R,

Macintyre

K,

Karim

AM,

Brown

L,

Hutchinson

P,

Kaufman

C,

et

al.

The

impact

of

life

skills

education

on

adolescent

sexual

risk

behaviors

in

KwaZulu-Natal,

South

Africa.

The

Journal

of

adolescent

health

:

official

publication

of

the

Society

for

Adolescent

Medicine.

2005

Apr;36(4):289-304.

PubMed

PMID:

15780784.

26.

Botvin

G,

Griffin

K.

Life

skills

training:

Empirical

findings

and

future

directions.

Journal

of

Primary

Prevention.

2004;25(2):211-32.

27.

Gorman

DM.

Does

measurement

dependence

explain

the

effects

of

the

Life

Skills

Training

program

on

smoking

outcomes?

Preventive

medicine.

2005

Apr;40(4):479-87.

PubMed

PMID:

15530601.

28.

Codony

M,

Alonso

J,

Almansa

J,

Bernert

S,

de

Girolamo

G,

de

Graaf

R,

et

al.

Perceived

need

for

mental

health

care

and

service

use

among

adults

in

Western

Europe:

results

of

the

ESEMeD

project.

Psychiatric

services.

2009

Aug;60(8):1051-8.

PubMed

PMID:

19648192.

29.

Pick

S,

Givaudan

M,

Poortinga

YH.

Sexuality

and

life

skills

education.

A

multistrategy

intervention

in

Mexico.

The

American

psychologist.

2003

Mar;58(3):230-4.

PubMed

PMID:

12772430.

30.

Taft

CT,

Street

AE,

Marshall

AD,

Dowdall

DJ,

Riggs

DS.

Posttraumatic

stress

disorder,

anger,

and

partner

abuse

among

Vietnam

combat

veterans.

Journal

of

family

psychology

:

JFP

:

journal

of

the

Division

of

Family

Psychology

of

the

American

Psychological

Association.

2007

Jun;21(2):270-7.

PubMed

PMID:

17605549.

31.

Weine

S,

Ukshini

S,

Griffith

J,

Agani

F,

Pulleyblank-Coffey

E,

Ulaj

J,

et

al.

A

family

approach

to

severe

mental

illness

in

post-war

Kosovo.

Psychiatry.

2005

Spring;68(1):17-27.

PubMed

PMID:

15899707.

32.

Siamian

H,

Naeimi

O,

Shahrabi

A,

Hassanzadeh

R,

Abazari

M,

Khademloo

M,

et

al.

The

Status

of

Happiness

and

its

Association

with

Demographic

Variables

among

the

Paramedical

Students.

J

Mazandaran

Univ

Med

Sci.

2012;21

(86):159-66.

33.

Argyle

M,

Martin

M,

Crossland

J.

Happiness

as

a

function

of

personality

and

social

encounters.

In:

Forgas

JP,

Innes

JM

(Eds).

Recent

advances

in

social

psychology:

An

international

perspective.

Netherlands:

Elsevier

Science

Publishers.

1989:189-203.

34.

Alipoor

A,

Noorbala

A.

A

Preliminary

Evaluation

of

the

Validity

and

Reliability

of

the

Oxford

Happiness

Questionnaire

in

Students

in

the

Universities

of

Tehran.

Iranian

Journal

of

Psychiatry

and

Clinical

Psychology.

1999;5(1&2):55-66.

35.

Goldberg

DP,

Hillier

VF.

A

scaled

version

of

the

General

Health

Questionnaire.

Psychological

medicine.

1979

Feb;9(1):139-45.

PubMed

PMID:

424481.

36.

Jenkins

R,

Elliott

P.

Stressors,

burnout

and

social

support:

nurses

in

acute

mental

health

settings.

Journal

of

Advanced

Nursing.

2004;48(6):622-31.

37.

Williams

P,

Goldberg

DP,

Mari

J.

The

validity

of

the

GHQ-28.

Social

Psychiatry.

1987;21:15-8.

38.

Ebrahimi

A,

Moulavi

H,

Mousavi

S,

Bornamanesh

A,

Yaghoubi

M.

Psychometric

properties

and

factor

structure

of

General

Health

Questionnaire

28

(GHQ-28)

in

Iranian

psychiatric

patients.

Journal

of

Research

in

Behavioural

Sciences.

2007;5(1):5-12.

39.

Fowers

B,

Olson

D.

ENRICH

Marital

Satisfaction

Scale:

A

brief

research

and

clinical

tool.

Journal

of

family

psychology

:

JFP

:

journal

of

the

Division

of

Family

Psychology

of

the

American

Psychological

Association.

1993;7(2):176-85.

40.

Kees

M,

Rosenblum

K.

Evaluation

of

a

psychological

health

and

resilience

intervention

for

military

spouses:

A

pilot

study.

Psychological

services.

2015;12(3):222.

41.

Elliott

TR,

Berry

JW,

Grant

JS.

Problem-solving

training

for

family

caregivers

of

women

with

disabilities:

a

randomized

clinical

trial.

Behaviour

research

and

therapy.

2009

Jul;47(7):548-58.

PubMed

PMID:

19361781.

Pubmed

Central

PMCID:

2737710.

42.

Layne

CM,

Saltzman

WR,

Poppleton

L,

Burlingame

GM,

Pasalic

A,

Durakovic

E,

et

al.

Effectiveness

of

a

school-based

group

psychotherapy

program

for

war-exposed

adolescents:

a

randomized

controlled

trial.

Journal

of

the

American

Academy

of

Child

and

Adolescent

Psychiatry.

2008

Sep;47(9):1048-62.

PubMed

PMID:

18664995.

43.

Hojjat

Sk,

Hatami

SE,

Rezaei

M,

Khalili

MN,

Talebi

MR.

The

efficacy

of

training

of

stress-coping

strategies

on

marital

satisfaction

of

spouses

of

veterans

with

post-traumatic

stress

disorder.

Electronic

Physician.

2016;8(4):2232-7.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC4886563.

44.

Ray

SL,

Vanstone

M.

The

impact

of

PTSD

on

veterans’

family

relationships:

an

interpretative

phenomenological

inquiry.

International

journal

of

nursing

studies.

2009

Jun;46(6):838-47.

PubMed

PMID:

19201406.

45.

Monson

CM,

Taft

CT,

Fredman

SJ.

Military-related

PTSD

and

Intimate

Relationships:

From

Description

to

Theory-Driven

Research

and

Intervention

Development.

Clinical

psychology

review.

2009

09/10;29(8):707-14.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC2783889.

46.

Sullivan

CP,

Elbogen

EB.

PTSD

Symptoms

and

Family

vs.

Stranger

Violence

in

Iraq

and

Afghanistan

Veterans.

Law

and

human

behavior.

2014

05/06;38(1):1-9.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC4394858.

47.

Reisman

M.

PTSD

Treatment

for

Veterans:

What’s

Working,

What’s

New,

and

What’s

Next.

Pharmacy

and

Therapeutics.

2016;41(10):623-34.

PubMed

PMID:

PMC5047000.

|