|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor)

DOI:10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93610

|

........................................................

|

|

Editorial

Dr.

Abdulrazak Abyad

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93623

Original Contribution

Self-monitoring

of Blood Glucose Among Type-2 Diabetic Patients:

An Analytical Cross-Sectional Study

[pdf]

Ahmed S. Alzahrani, Rishi K. Bharti, Hassan

M. Al-musa, Shweta Chaudhary

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93624

White

coat hypertension may actually be an acute phase

reactant in the body

[pdf]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, Orhan Ayyildiz, Orhan Ekrem

Muftuoglu, Mehmet Gundogdu, Abdulrazak Abyad,

Lesley Pocock

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93625

Case Report

An

Unusual Persistent Mullerian Duct Syndrome in

a child in Abha city: A Case Report

[pdf]

Youssef Ali Mohamad Alqahtani, Abdulrazak Tamim

Abdulrazak, Hessa Gilban, Rasha Mirdad, Ashwaq

Y. Asiri, Rishi Kumar Bharti, Shweta Chaudhary

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93628

Population and Community

Studies

Prevalence

of abdominal obesity and its associated comorbid

condition in adult Yemeni people of Sana’a

City

[pdf]

Mohammed Ahmed Bamashmos

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93626

Smoking

may even cause irritable bowel syndrome

[pdf]

Mehmet Rami Helvaci, Guner Dede, Yasin Yildirim,

Semih Salaz, Abdulrazak Abyad, Lesley Pocock

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93629

Systematic

literature review on early onset dementia

[pdf]

Wendy Eskine

DOI: 10.5742/MEWFM.2019.93627

|

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

AUSTRALIA

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| March 2019 - Volume

17, Issue 3 |

|

|

Smoking may even cause irritable

bowel syndrome

Mehmet Rami Helvaci

(1)

Guner Dede (2)

Yasin Yildirim (2)

Semih Salaz (2)

Abdulrazak Abyad (3)

Lesley Pocock (4)

(1) Specialist of Internal Medicine, MD

(2) General practitioner, MD

(3) Middle-East Academy for Medicine of Aging,

MD

(4) medi-WORLD International

Corresponding

author:

Mehmet

Rami Helvaci, MD

07400, ALANYA, Turkey

Phone: 00-90-506-4708759

Email: mramihelvaci@hotmail.com

|

Abstract

Background: Smoking induced chronic

vascular endothelial inflammation may

even cause irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Method: IBS is diagnosed according

to Rome II criteria in the absence of

red flag symptoms.

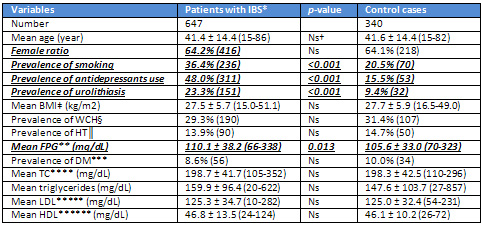

Results: The study included 647

patients with IBS and 340 control cases.

Mean age of the IBS patients was 41.4

years. Interestingly, 64.2% of the IBS

patients were female. Prevalence of smoking

was higher in the IBS cases (36.4% versus

20.5%, p<0.001). Similarly, prevalence

of antidepressants use was higher in the

IBS patients (48.0% versus 15.5%, p<0.001).

Additionally, prevalence of urolithiasis

was also higher in the IBS group (23.3%

versus 9.4%, p<0.001). Mean body mass

index values were similar in the IBS and

control groups (27.5 versus 27.7 kg/m2,

p>0.05, respectively). Prevalence of

white coat hypertension was also similar

in them (29.3% versus 31.4%, p>0.05,

respectively). Although prevalence of

hypertension and diabetes mellitus and

mean values of total cholesterol, triglycerides,

low density lipoproteins, and high density

lipoproteins were all similar in them,

mean value of fasting plasma glucose (FPG)

was significantly higher in the IBS group

(110.1 versus 105.6 mg/dL, p= 0.013).

Conclusion: IBS may be a low-grade

inflammatory process being initiated with

infection, inflammation, psychological

disturbances-like stresses, and eventually

terminates with dysfunctions of gastrointestinal

and genitourinary tracts and other systems

of the body. Although there may be several

possible causes of IBS, smoking induced

chronic vascular endothelial inflammation

may even cause IBS. The higher FPG in

the IBS patients should be researched

with further studies.

Key words:

Smoking, irritable bowel syndrome,

metabolic syndrome, fasting plasma glucose

|

One of most frequent applications to Internal

Medicine Polyclinics are due to recurrent upper

abdominal discomfort (1). Although gastroesophageal

reflux disease, esophagitis, duodenal or gastric

ulcers, erosive gastritis or duodenitis, celiac

disease, chronic pancreatitis, and malignancies

are found among possible causes, irritable bowel

syndrome (IBS) may be one of the most frequently

diagnosed diseases, clinically. Flatulence,

periods of diarrhea or constipation, repeated

toilet visits due to urgent evacuation or early

filling sensation, excessive straining, feeling

of incomplete evacuation, frequency, urgency,

reduced feeling of well-being, and eventually

disturbed social life are often reported by

the IBS patients. Although many patients relate

onset of symptoms to intake of food, and often

incriminate specific food items, a meaningful

dietary role is doubtful in the IBS. According

to literature, 10-20% of the general population

have IBS, and it is more common among females

with unknown causes (2). Psychological factors

seem to precede onset or exacerbation of gut

symptoms, and many potentially psychiatric disorders

including anxiety, depression, or sleep disorders

frequently coexist with the IBS (3). For example,

thresholds for sensations of initial filling,

evacuation, urgent evacuation, and utmost tolerance

recorded via a rectal balloon significantly

decreased by focusing the examiners' attention

on gastrointestinal stimuli by reading pictures

of gastrointestinal malignancies in the IBS

cases (4). So although IBS is described as a

physical instead of a psychological disorder

according to Rome II guidelines, psychological

factors may be crucial for triggering of the

physical changes in the body. IBS is actually

defined as a brain-gut dysfunction according

to the Rome II criteria, and it may have more

complex mechanisms affecting various systems

of the body with a low-grade inflammatory state

(5). For example, IBS may even terminate with

chronic gastritis, urolithiasis, and hemorrhoid

in a significant proportion of patients (6-8).

Similarly, some authors studied the role of

inflammation via colonic biopsies in 77 patients

with IBS (9). Although 38 patients had normal

histology, 31 patients demonstrated microscopic

inflammation and eight patients fulfilled criteria

for lymphocytic colitis. However, immunohistology

revealed increased intraepithelial lymphocytes

as well as increased CD3 and CD25 positive cells

in lamina propria of the group with "normal"

histology. These features were more evident

in the microscopic inflammation group who additionally

revealed increased neutrophils, mast cells,

and natural killer cells. All of these immunopathological

abnormalities were the most evident in the lymphocytic

colitis group who also demonstrated HLA-DR staining

in the crypts and increased CD8 positive cells

in the lamina propria (9). A direct link between

the immunologic activation and IBS symptoms

was provided by work of some other authors (10).

They demonstrated not only an increased incidence

of mast cell degranulation in the colon but

also a direct correlation between proximity

of mast cells to neuronal elements and pain

severity in the IBS (10). In addition to these

findings, there is some evidence for extension

of the inflammatory process behind the mucosa.

Some authors addressed this issue in 10 patients

with severe IBS by examining full-thickness

jejunal biopsies obtained via laparoscopy (11).

They detected a low-grade infiltration of lymphocytes

in myenteric plexus of nine patients, four of

whom had an associated increase in intraepithelial

lymphocytes and six demonstrated evidence of

neuronal degeneration. Nine patients had hypertrophy

of longitudinal muscles and seven had abnormalities

in number and size of interstitial cells of

Cajal. The finding of intraepithelial lymphocytosis

was consistent with some other reports in the

colon (9) and duodenum (12). On the other hand,

smoking is a well-known cause of chronic vascular

endothelial inflammation all over the body.

We tried to understand whether or not smoking

induced chronic vascular endothelial inflammation

all over the body is found among one of the

possible causes of the IBS.

The

study

was

performed

in

the

Internal

Medicine

Polyclinic

of

the

Dumlupinar

University

between

August

2005

and

March

2007.

Consecutive

patients

with

upper

abdominal

discomfort

were

taken

into

the

study.

Their

medical

histories

including

smoking

habit,

hypertension

(HT),

diabetes

mellitus

(DM),

and

already

used

medications

including

antidepressants

at

least

for

a

period

of

six

months

were

learned.

A

routine

check

up

procedure

including

fasting

plasma

glucose

(FPG),

triglycerides,

low

density

lipoproteins

(LDL),

high

density

lipoproteins

(HDL),

erythrocyte

sedimentation

rate,

C-reactive

protein,

albumin,

thyroid

function

tests,

creatinine,

urinalysis,

hepatic

function

tests,

markers

of

hepatitis

A

virus,

hepatitis

B

virus,

hepatitis

C

virus,

and

human

immunodeficiency

virus,

a

posterior-anterior

chest

x-ray

film,

an

electrocardiogram,

a

Doppler

echocardiogram

in

case

of

requirement,

an

abdominal

ultrasonography,

an

abdominal

X-ray

graphy

in

supine

position,

and

a

questionnaire

for

IBS

was

performed.

IBS

is

diagnosed

according

to

Rome

II

criteria

in

the

absence

of

red

flag

symptoms

including

pain

and

diarrhea

that

awakens/interferes

with

sleep,

weight

loss,

fever,

and

abnormal

physical

examination

findings.

An

additional

intravenous

pyelography

was

performed

just

in

suspected

cases

from

presenting

urolithiasis

as

a

result

of

the

urinalysis

and

abdominal

X-ray

graphy.

So

urolithiasis

was

diagnosed

either

by

medical

history

or

as

a

result

of

clinical

findings.

Patients

with

a

history

of

eating

disorders

including

anorexia

nervosa,

bulimia

nervosa,

compulsive

overeating,

or

binge

eating

disorder,

insulin

using

diabetics,

and

patients

with

devastating

illnesses

including

malignancies,

acute

or

chronic

renal

failure,

cirrhosis,

hyper-

or

hypothyroidism,

and

heart

failure

were

excluded

to

avoid

their

possible

effects

on

weight.

Current

daily

smokers

at

least

for

six

months

and

cases

with

a

history

of

five

pack-year

were

accepted

as

smokers.

Body

mass

index

(BMI)

of

each

case

was

calculated

by

the

measurements

of

the

same

physician

instead

of

verbal

expressions.

Weight

in

kilograms

is

divided

by

height

in

meters

squared

(13).

Cases

with

an

overnight

FPG

level

of

126

mg/dL

or

higher

on

two

occasions

or

already

using

antidiabetic

medications

were

defined

as

diabetics.

An

oral

glucose

tolerance

test

with

75

grams

glucose

was

performed

in

cases

with

FPG

levels

between

100

and

126

mg/dL,

and

diagnosis

of

cases

with

2-hour

plasma

glucose

levels

of

200

mg/dL

or

higher

is

DM

(13).

Office

blood

pressure

(OBP)

was

checked

after

a

5-minute

rest

in

seated

position

with

mercury

sphygmomanometer

on

three

visits,

and

no

smoking

was

permitted

during

the

previous

2

hours.

Ten-day

twice

daily

measurements

of

blood

pressure

at

home

(HBP)

were

obtained

in

all

cases,

even

in

normotensives

in

the

office

due

to

the

risk

of

masked

HT

after

a

10-minute

education

session

about

proper

blood

pressure

(BP)

measurement

techniques

(14).

The

education

included

recommendation

of

upper

arm

while

discouraging

wrist

and

finger

devices,

using

a

standard

adult

cuff

with

bladder

sizes

of

12

x

26

cm

for

arm

circumferences

up

to

33

cm

in

length

and

a

large

adult

cuff

with

bladder

sizes

of

12

x

40

cm

for

arm

circumferences

up

to

50

cm

in

length,

and

taking

a

rest

at

least

for

a

period

of

5

minutes

in

the

seated

position

before

measurements.

An

additional

24-hour

ambulatory

blood

pressure

monitoring

(ABP)

was

not

required

due

to

an

equal

efficacy

of

the

method

with

HBP

measurement

to

diagnose

HT

(15).

Eventually,

HT

is

defined

as

a

mean

BP

of

140/90

mmHg

or

higher

on

HBP

measurements

and

white

coat

hypertension

(WCH)

is

defined

as

an

OBP

of

140/90

mmHg

or

higher,

but

a

mean

HBP

value

of

lower

than

140/90

mmHg

(14).

Eventually,

all

patients

with

the

IBS

were

collected

into

the

first

and

age

and

sex-matched

controls

were

collected

into

the

second,

groups.

Mean

BMI,

FPG,

total

cholesterol

(TC),

triglycerides,

LDL,

and

HDL

values

and

prevalences

of

smoking,

antidepressants

use,

urolithiasis,

WCH,

HT,

and

DM

were

detected

in

each

group

and

compared

in

between.

Mann-Whitney

U

test,

Independent-Samples

T

test,

and

comparison

of

proportions

were

used

as

the

methods

of

statistical

analyses.

The

study

included

647

patients

with

the

IBS

and

340

control

cases,

totally.

The

mean

age

of

the

IBS

patients

was

41.4

±

14.4

(15-86)

years.

Interestingly,

64.2%

(416)

of

the

IBS

patients

were

female.

Prevalence

of

smoking

was

significantly

higher

in

cases

with

the

IBS

(36.4%

versus

20.5%,

p<0.001).

Similarly,

prevalence

of

antidepressants

use

was

higher

in

cases

with

the

IBS

(48.0%

versus

15.5%,

p<0.001).

Beside

that

prevalence

of

urolithiasis

was

also

higher

in

the

IBS

group

(23.3%

versus

9.4%,

p<0.001).

Mean

BMI

values

were

similar

both

in

the

IBS

and

control

groups

(27.5

versus

27.7

kg/m2,

p>0.05,

respectively).

Additionally,

prevalence

of

WCH

was

similar

in

both

groups,

too

(29.3%

versus

31.4%,

p>0.05,

respectively).

Although

prevalence

of

HT

and

DM

and

mean

values

of

TC,

triglycerides,

LDL,

and

HDL

were

all

similar

in

both

groups

(p>0.05

for

all),

mean

value

of

FPG

was

significantly

higher

in

the

IBS

group

with

unknown

reasons,

yet

(110.1

versus

105.6

mg/dL,

p=

0.013)

(Table

1).

Table

1:

Comparison

of

patients

with

irritable

bowel

syndrome

and

control

cases

*Irritable

bowel

syndrome

†Nonsignificant

(p>0.05)

‡Body

mass

index

§White

coat

hypertension

?Hypertension

**Fasting

plasma

glucose

***Diabetes

mellitus

****Total

cholesterol

*****Low

density

lipoproteins

******High

density

lipoproteins *Irritable

bowel

syndrome

†Nonsignificant

(p>0.05)

‡Body

mass

index

§White

coat

hypertension

?Hypertension

**Fasting

plasma

glucose

***Diabetes

mellitus

****Total

cholesterol

*****Low

density

lipoproteins

******High

density

lipoproteins

| | |