|

|

|

Medicine and Society

........................................................

Case Report

........................................................

Continuing Education

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| January 2015 -

Volume 13 Issue 1 |

|

Women's

health Aspect In Humanitarian Missions And Disasters:

Jordanian Royal Medical Services Experience

Fatima

Al-Odwan

Suhair Wreikat

Specialist of obstetric and gynecology,

Royal Medical Services

Jordan

Correspondence:

Fatima Al-Odwan

Suhair Wreikat

Specialist of obstetric and gynecology,

Royal Medical Services

Jordan

Email: mkateeb@lycos.com

|

Abstract

Objective: To

review women's health problems in patients

who presented to Royal Medical Services

humanitarian missions over a 3 year period.

Design and method: Analysis of

humanitarian missions of RMS data and

records over three year period (2009-2011)

in regards to women's health issues, was

done. The data were analyzed in regards

to number of women seen, the presenting

conditions, and prevalence of domestic

violence in these cases.

Results: During

the 3 year period 72 missions were deployed

to 4 locations ( Gaza, Ram Allah -West

Bank, Jeneen-West Bank, and Iraq). Total

numbers of females seen in this period

was 86,436 women accounting for 56% of

adults patients seen by RMS humanitarian

missions. Acute injuries were responsible

for 32% of the cases, chronic diseases

for 52% and women's health issues for

the rest. Domestic violence was encountered

in 11% of the cases. Pregnancy related

problems were the main reason for presentation

(38%). Contraception was the second reason

for seeking help and was seen in 25% of

cases.

Conclusion: Women's

health care providers are needed to advise,

assist, and support public health authorities

in planning for and serving during a disaster.

Emergency preparedness is essential to

maintaining healthy pregnancies and ensuring

good outcomes for pregnant women and their

infants who endure disasters.

Key words: women's

health problems, humanitarian missions,

Royal Medical Services(RMS).

|

Gender can also place women and men at different

risks of disaster. Women suffer in the aftermath

of disasters when social networks are frayed,

when family and kin are displaced, and when

they feel the cumulative effects of caring for

others including for men and boys, are not well

served by disaster mental health care and facilities.

Examples from previous disaster events demonstrated

this gender difference: In 1976, in the technological

disaster of Seveso, Italy, the population was

exposed to dioxin. Biologic differences between

the sexes were seen: 15 years later, more men

died of rectal and lung cancer, whereas more

women died of diabetes. In the Indian Ocean

tsunami in 2004, the ratio of deaths between

women and men was 3:1 because men were stronger,

women had not learned to swim, and women's long

hair got entangled in debris.

In the 1993 earthquake in Maharashtra, India,

more women and children died than men because

the women were in the homes, whereas the men

were out in the fields. Conversely, social roles

determined that men were more affected than

women during the 1985 Chernobyl disaster. The

soldiers and male civilians predominantly cleaned

up the site and as a result were exposed to

more radiation. Cultural norms have prevented

women from seeking help after a disaster, especially

in certain regions where interacting with men

is strictly forbidden. (2) Social norms have

demonstrated that women bear more of the responsibility

of caring for children, elderly, and the sick

or injured.

Women also face an increased risk of domestic

violence: Studies have found that there are

many more calls to women's shelters as much

as year after an emergency, the aim of this

review is to study the effect on disasters on

women's health. Royal Medical Services has been

involved in more than 100 humanitarian missions

over the last 15 years in more than 15 locations

all over the world. The aim of this study is

to review women's health problems in patients

presented to RMS humanitarian missions over

a 3 year period.

Analysis of humanitarian

missions of RMS data and

records over a three year

period ( 2009-2011) in

regards to women health

issues was done. The data

were analyzed in regards

to number of women seen,

the presenting conditions,

and prevalence of domestic

violence in these cases.

During 3 years period

72 missions were deployed

to 4 locations ( Gaza,

Ram Allah -West Bank,

Jeneen-West Bank, and

Iraq).

Total number of females

seen in this period

was 86,436 women accounting

for 56% of adult patients

seen by RMS humanitarian

missions . Table 1 shows

the age distribution

of these women, and

Table 2 shows the presenting

conditions.

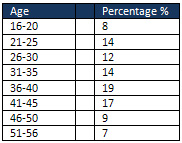

Table 1: Age of women

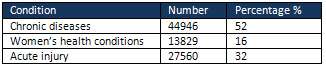

Table 2: Condition of

presentation

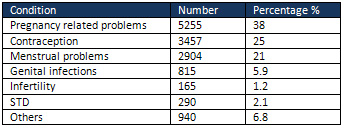

Table 3: Women's Health

condition

Acute injuries were

responsible for 32%

of the cases, chronic

diseases for 52%, and

women's health issues

for the rest. Domestic

violence was encountered

in 11% of the cases.

Pregnancy related problems

was the main reason

for presentation(38%).

Contraception was the

second reason for seeking

help and was seen in

25% of cases. Menstrual

related problems were

responsible for 21%

of cases, and genital

infections were responsible

for 8% of cases. Among

them STD was not prevalent

in the women who presented

(only 2.1%). Surprisingly

infertility problem

was the main cause of

presentation in 3% of

cases.

Pregnant

women,

newborns,

and

infants

may

be

disproportionately

harmed

by

natural

disasters.

The

lack

of

resources,

such

as

food

and

clean

water,

lack

of

access

to

health

care

and

medications,

as

well

as

psychologic

stress

in

the

aftermath

of

disasters

increase

pregnancy-related

morbidities.

After

Hurricane

Katrina,

the

Centers

for

Disease

Control

and

Prevention

found

that

the

14

Federal

Emergency

Management

Agency

designated

counties

and

parishes

affected

by

the

hurricane

had

a

significant

increase

in

the

number

of

women

who

received

late

or

no

prenatal

care.

In

the

designated

counties

in

Mississippi,

the

percentage

of

inadequate

prenatal

care

increased

significantly

from

2.3%

to

3.3%

(3).

In

Louisiana,

among

Hispanic

women,

it

increased

from

2.3%

to

3.9%

(3).

Infants

who

were

born

to

pregnant

women

living

within

a

2-mile

radius

of

the

World

Trade

Center

on

9/11

were

found

to

have

a

higher

rate

of

intrauterine

growth

restriction,

decreased

birth

weight,

and

a

small

head

circumference

.

In

a

study

that

monitored

birth

outcomes

following

Hurricane

Katrina,

women

who

experienced

three

or

more

severe

traumatic

situations

during

the

hurricane,

such

as

feeling

as

though

one's

life

was

in

danger,

walking

through

flood

waters,

or

having

a

loved

one

die,

were

found

to

have

a

higher

rate

of

low

birth

weight

infants

and

an

increase

in

preterm

deliveries.

Additionally,

disruption

of

the

health

care

system

may

result

in

the

separation

of

mothers

and

infants.

For

example,

during

Hurricane

Katrina,

many

critically

ill

hospitalized

infants

were

transported

to

medical

facilities

outside

of

New

Orleans

without

their

mothers.

The

separation

of

mothers

and

their

infants

can

interfere

with

breastfeeding

as

well

as

create

additional

stress

for

the

mothers.

These

pregnancy

morbidities

can

be

prevented

by

developing

an

emergency

plan

that

addresses

them.

As

providers

of

women's

health

care,

the

involvement

of

the

obstetrician-gynecologist

in

disaster

response

is

essential.

This

can

be

done

at

the

local

level

through

a

hospital

emergency

preparedness

committee

or

a

community

group

attached

to

the

fire

department

or

police

department

and

at

the

state

level.

Disaster

Preparedness

for

the

Health

Care

System

and

Providers

Caring

for

Pregnant

Women

Although

a

"one-size

fits

all"

emergency

plan

is

difficult

to

apply

to

all

disasters,

there

are

common

distresses

experienced

by

all

pregnant

women

regardless

of

the

nature

of

the

disaster.

Pregnant

women

should

be

encouraged

to

develop

evacuation

plans

in

the

event

there

is

enough

forewarning

to

allow

for

evacuation.

The

Red

Cross

provides

emergency

preparedness

checklists

for

specific

disasters.

However,

when

evacuation

is

not

possible,

the

health

care

for

women

in

the

antepartum,

intrapartum,

and

postpartum

periods

needs

to

be

safely

managed.

For

women

in

the

antepartum

period,

maintaining

prenatal

care

is

of

utmost

importance.

Health

care

providers

outside

the

perimeter

of

the

disaster

should

be

willing

to

accept

evacuees

in

an

effort

to

ensure

continuation

of

prenatal

care.

State

and

local

governments

should

establish

local

facilities

where

prenatal

care

and

obstetric

services

can

be

provided

for

those

women

unable

to

evacuate.

Accessing

prenatal

records

is

important

in

maintaining

prenatal

care.

This

will

be

impossible

if

written

records

are

destroyed

because

of

the

disaster

or

if

interruption

in

electricity

prohibits

access

to

electronic

medical

records.

In

preparation,

clinicians

should

make

patients

aware

of

their

specific

prenatal

issues

as

well

as

provide

them

with

key

portions

of

their

medical

records.

This

is

especially

true

in

areas

where

natural

disasters

are

seasonal

and

may

be

likely

to

occur.

Also,

health

care

providers

of

prenatal

care

should

increase

patients'

awareness

of

the

signs

of

preterm

labor

and

other

obstetric

emergencies

and

the

action

to

take

in

the

event

of

these

emergencies.

Obstetric

care

at

a

designated

facility

is

ideal,

and

it

is

the

role

of

public

health

officials

in

an

area

to

designate

and

equip

obstetric

care

facilities,

publicize

which

facilities

in

a

given

area

will

offer

obstetric

services,

identify

alternative

safe

delivery

sites,

and

arrange

for

the

staffing

of

the

facilities.

Individual

obstetric

care

providers

are

urged

to

assist

public

health

officials

and

to

practice

within

the

obstetric

care

system

that

is

established.

However,

there

are

several

factors

that

may

contribute

to

difficulty

in

accessing

obstetric

health

care

facilities

during

a

disaster.

The

health

care

system

may

become

inundated

with

other

health

emergencies,

which

could

decrease

the

resources

available

to

pregnant

women.

Also,

physical

barriers,

such

as

impassible

roads,

demolished

bridges

and

fire

lines,

may

serve

as

obstacles

to

accessing

obstetric

care

facilities.

These

hindrances

may

result

in

women

giving

birth

outside

of

health

care

facilities.

To

prepare,

clinicians

should

make

pregnant

women

who

reside

in

locations

subject

to

seasonal

or

frequent

environmental

emergencies

aware

of

the

availability

of

emergency

birth

kits

.

These

kits

have

all

of

the

essential

equipment

necessary

should

a

birth

occur

outside

of

a

birthing

facility.

During

a

disaster,

women

who

are

not

breastfeeding

may

have

difficulty

in

providing

food

for

their

newborns.

Some

new

mothers

may

plan

to

bottle-feed

their

newborns.

However,

during

a

disaster,

there

may

not

be

access

to

clean

water

for

sterilization

of

bottles

or

access

to

formula.

Encouraging

and

establishing

breastfeeding

as

a

part

of

routine

care

ensures

that

mothers

are

able

to

feed

their

newborns

in

the

event

of

a

disaster.

Additionally,

health

care

providers

should

be

educated

in

lactation

to

assist

new

mothers

in

initiating

breastfeeding

in

the

immediate

phase

of

a

disaster.

For

mothers

who

are

less

than

6

months

postpartum,

even

if

they

have

not

previously

established

lactation,

relactation

can

be

established

and

should

be

encouraged.

For

those

mothers

who

choose

not

to

begin

relactation

or

are

beyond

the

6-month

period,

ready-to-feed

infant

formula

in

a

single-serving

bottle

should

be

provided.

Disaster

Preparedness

for

the

Health

Care

System

and

Providers

Caring

for

Nonpregnant

Women

Providing

contraception

for

postpartum

and

nonpregnant

women

during

a

disaster

is

also

important

to

prevent

unintended

pregnancies.

Contraception

should

be

provided

in

the

form

of

emergency

contraception

as

well

as

prophylactic

contraception.

Providing

condoms

allows

for

the

prevention

of

not

only

unintended

pregnancies

but

also

decreases

the

transmission

of

sexually

transmitted

diseases.

For

women

who

are

using

reversible

contraception

in

the

form

of

pills,

the

ring,

or

the

patch,

these

prescription

medications

should

be

provided

to

enable

these

women

to

maintain

their

current

form

of

birth

control.

When

possible,

emergency

health

care

facilities

should

stock

and

dispense

a

variety

of

contraceptive

products.

Mental

Health

Considerations

Involvement

in

a

disaster

situation

causes

and

exacerbates

tremendous

anxiety,

depression,

and

grief.

Post-disaster,

patients

and

health

care

providers

need

to

be

aware

of

the

signs

of

mental

distress

requiring

medical

attention.

The

Centers

for

Disease

Control

and

Prevention

offers

information

and

resources

for

mental

health

care

during

and

after

disasters.

This

can

be

accessed

at

http://www.bt.cdc.gov/mentalhealth/.

Prevention

of

Violence

Against

Women

During

a

Disaster

Women

are

subjected

to

and

vulnerable

to

intimate

partner

violence

and

sexual

assault

during

disasters

(9,

10).

Similar

to

the

conditions

found

in

refugee

camps

where

sexual

violence

also

is

increased,

during

the

phases

of

a

disaster

women

are

isolated

from

their

families

and

without

physical

protection.

The

United

Nations

Refugee

Agency,

in

developing

guidelines

for

prevention

and

response

to

sexual

violence

against

refugees,

has

identified

some

contributing

circumstances:

1)

male

perpetrators'

dominance

over

female

victims,

2)

psychologic

strains

in

refugee

camps,

3)

absence

of

support

systems

for

protection,

4)

crowded

facilities,

5)

lack

of

physical

protection,

6)

general

lawlessness,

7)

alcohol

and

drug

abuse,

8)

politically

motivated

violence

against

refugees,

and

9)

single

females

separated

from

male

family

members

(5).

Ironically,

these

same

circumstances

existed

among

the

Hurricane

Katrina

evacuees

and

were

likely

responsible

for

the

many

personal

accounts

of

rape

that

occurred

in

evacuation

shelters.

Establishing

safety,

order,

and

the

rule

of

law

in

shelters

for

disaster

survivors

is

paramount

to

the

protection

of

women

from

sexual

assault.

In

the

event

that

sexual

violence

does

occur,

appropriate

and

sensitive

services

should

be

available

to

victims,

including

emergency

contraception

and

sexual

assault

forensic

examiners

or

sexual

assault

nurse

examiners.

Disasters are unplanned

but can be anticipated.

Emergency preparedness

is essential to maintaining

healthy pregnancies and

ensuring good outcomes

for pregnant women and

their infants who endure

disasters. Developing

an evacuation plan is

the first step. However,

if evacuation is not possible,

identifying local health

care facilities that can

provide obstetric care,

discussing the availability

of emergency birth kits,

and emphasizing the importance

of lactation are key steps

to facing the many challenges

of a disaster that are

unique to pregnant women.

Postpartum and nonpregnant

women must have access

to contraception. Women's

health care providers

are needed to advise,

assist, and support public

health authorities in

planning for and serving

during a disaster. Clinicians

also should encourage

local and state governments

to provide shelters that

are safe and secure to

prevent violence against

women.

1.

Toner

E,

Waldhorn

R,

Franco

C,

Courtney

B,

Rambhia

K,

Norwood

A,

Inglesby

TV,

O'Toole

T.

Hospitals

Rising

to

the

Challenge:

The

First

Five

Years

of

the

U.S.

Hospital

Preparedness

Program

and

Priorities

Going

Forward.

Prepared

by

the

Center

for

Biosecurity

of

UPMC

for

the

U.S.

Department

of

Health

and

Human

Services

under

Contract

No.

HHSO100200700038C.

2009.

2.

Women

and

Infants

Services

Package

(WISP),

from

the

National

Working

Group

for

Women

and

Infant

Needs

in

Emergencies,

White

Ribbon

Alliance.

Accessed

March

24,

2008

from

http://www.whiteribbonalliance.org/Resources/Documents/WISP

.Final.07.27.07.pdf.

3.

Hamilton

B,

Sutton

P,

Matthews

TJ,

Martin

J,

Ventura

S.

The

Effect

of

Hurricane

Katrina:

Births

in

the

U.S.

Gulf

Coast

Region,

Before

and

After

the

Storm.

National

Vital

Statistics

Report.

Vol

58,

No

2.

4.

Callaghan

W,

Rasmussen,

S,

Jamieson

D,

Ventura

S,

Farr

S,

Sutton

P,

Mathews,

T,

Hamilton

B,

Shealy

K,

Brantley

D,

Posner

S.

Health

Concerns

of

Women

and

Infants

in

Times

of

Natural

Disasters:

Lessons

Learned

from

Hurricane

Katrina.

Maternal

and

Child

Health

Journal.

2007;

11(4):

307-311.

5.

Lederman

SA,

Rauh

V,

Weiss

L,

Stein

JL,

Hoepner

LA,

Becker

M,

et

al.

The

effects

of

the

World

Trade

Center

event

on

birth

outcomes

among

term

deliveries

at

three

lower

Manhattan

hospitals.

Environ

Health

Perspect

2004;112:1772-8.

6.

Xiong

X,

Harville

E,

Mattison

D,

Elkind-Hirsch

K,

Pridjian

G,

Buekens

P.

Exposure

to

Hurricane

Katrina,

Post-Traumatic

Stress

Disorder

and

Birth

Outcomes.

Am

J

Med

Sci

2008

August;

336(2):

111-115.

doi:

10.1097/MAJ.

0b013e318180f21c.

7.

American

Red

Cross,

"Preparedness

Fast

Facts:

Emergency-Specific

Preparedness

Information".

Copyright

2009.

The

American

National

Red

Cross.

http://www.redcross.org/portal/site/en/menuitem.86f46a12f382290517a8f210b80f78a0/?vgnextoid=92d51a53f1c37110VgnVCM100

0003481a10aRCRD

8.

La

Leche

League

International,

"When

an

Emergency

Strikes

Breastfeeding

Can

Save

Lives,

Part

2,"

media

release,

September

1,

2005.

Accessed

October

3,

2006

from

http://www.lalecheleague.org/Release/emergency2.html

9.

United

Nations

High

Commissioner

for

Refugees

(UNHCR).

Prevention

and

Response

to

Sexual

and

Gender-Based

Violence

in

Refugee

Situations.

Proceedings

of

the

Inter-Agency

Lessons

Learned

Conference,

Geneva

(March

27-29,

2001).

Available

at:

http://action.web.ca/home/cpcc/attach/prevention%20and%20responses.pdf

10.

Thornton,

W.,

Voigt,

L.

"Disaster

Rape:

Vulnerability

of

Women

to

Sexual

Assaults

During

Hurricane

Katrina."

Journal

of

Public

Management

&

Social

Policy.

Fall

2007.

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|