|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................

|

Original

Contribution/Clinical Investigation

|

|

|

<-- Turkey -->

Very high

levels of C-reactive protein should alert the

clinician to the development of acute chest

syndrome in sickle cell patients

[pdf version]

Can Acipayam, Sadik Kaya, Mehmet Rami Helvaci,

Gül Ilhan, Gönül Oktay

<-- Jordan -->

Seroprevalence

of HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among

blood donors at Blood Bank of King Hussein Medical

Center: A 3 Year Study

[pdf

version]

Baheieh Al Abaddi, Maha Al Amr, Lamees Abasi,

Abeer Saleem, Nisreen Abu hazeem, Ahmd Marafi

|

|

........................................................ |

Medicine and Society

........................................................

International Health

Affairs

.......................................................

Education

and Training

.......................................................

Continuing

Medical Education

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| August 2014 -

Volume 12 Issue 6 |

|

Training

medical students in general practices: Patients'

attitudes

R. P. J .C. Ramanayake (1)

A. H. W. de Silva (2)

D. P. Perera (2)

R. D. N. Sumanasekera (2)

K. A. T. Fernando (3)

L. A. C. L. Athukorala (3)

(1) Senior Lecturer, Department of Family

Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of

Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

(2) Lecturer, Department

of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University

of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

(3) Demonstrator,

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine,

University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

Correspondence:

Dr. R. P. J. C. Ramanayake

Senior

Lecturer, Department of Family Medicine, Faculty

of Medicine,

University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka.

Mobile: 0094773308700

Email:

rpjcr@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Introduction:

Training medical students in the setting

of family/general practice has increased

considerably in the past few decades in

Sri Lanka with the introduction of family

medicine into the undergraduate curriculum.

This study was conducted to explore patients'

attitudes towards training students in

fee levying general practices.

Methodology: Six general practices,

to represent different practices (urban,

semi urban, male and female trainers)

where students undergo training, were

selected for the study. Randomly 50 adult

patients were selected from each practice

and they responded to a self administered

questionnaire following a consultation

where medical students had been present.

Results: 300 patients (57.2 % females)

participated in the study. 44.1% had previously

experienced students. 30.3% were able

to understand English. Patients agreed

to involvement of students; taking histories

(95.3%), examination (88.5%), looking

at reports (96.6) and presence during

consultation (88.3 %). Patients' perceived

no change in duration (55%) or quality

(56.3%) of the consultation due to the

presence of students. The majority (78%)

preferred if doctor student interaction

took place in their native language. 45.8%

expected prior notice regarding student

participation and two to three students

were the preferred number. 93.6% considered

their participation as a social service

and only 8.8% expected a payment.

Conclusion: The vast majority of

the patients accepted the presence of

students and were willing to participate

in this education process without any

reservation. Their wishes should be respected.

The outcome of this study is an encouragement

to educationists and GP teachers.

Key words: Medical students, training,

General practice, patients' attitudes

|

There is a growing trend that undergraduate teaching

should take place more within the community, primarily

in the general practices(1,2) and as a result

worldwide Family medicine has come into the core

of the medical curriculum during the last few

decades.(3,4) That trend has invaded the Sri Lankan

medical schools as well and it is now well established

in most of the medical schools in the country.(5)

The reasons for this trend are many; everywhere

in the world in-patient care as a proportion of

all medical care is decreasing.(4,6) Diseases

which required in-patient care earlier no longer

do so due to the invention of newer medications

and newer techniques and accessibility of general

practitioners to investigations, telemedicine

and the internet.(4) The duration of stay in hospitals

for diseases which require admission has also

reduced considerably due to more efficient newer

medications and techniques. Educationally, there

are implications on undergraduate training due

to this trend. The morbidity seen in a hospital

ward has become less and less representative of

the overall morbidity in the whole population

and the opportunity for hands on experience for

students has reduced.(4) In the mean time community

offers a wealth of teaching opportunities for

medical students, a fact which was recognized

by the General medical council's directive, Tomorrow's

doctors(GMC,1993)(2).

General practitioner teachers have also transformed

from their original role as teachers of behavioral

science and general practice(7) into teachers

of clinical skills, with excellent access to a

wide range of patients.(8,9) It has been found

that community based teaching is as effective

as hospital based teaching of basic clinical skills.(10,11)

General practices offer a highly personalized

teaching in an environment where the importance

of social, economic, psychological and cultural

influences on a patient's illness and the family

response can be experienced firsthand. (12) It

is also an opportunity for students to get an

insight into the socio-economic environment of

patients and the local resources available to

them.

Participating in a general practice clerkship

has been shown to stimulate students to choose

general practice for their career(13) and students

who will take on another specialty will have gained

an understanding of primary care. (14)

Training undergraduates in family practices converts

an activity between two parties (doctor and patient)

into a three party affair.(15) It's in the privacy

of the consultation room that patients divulge

and discuss some sensitive issues and the presence

of students could affect the doctor patient relationship

and interaction. In a family practice patients

are autonomous and the majority of the patients

are ambulatory. They spend only a limited time

in a family practice and student participation

could lead to delays. Patients' consent to participate

in medical education is often taken for granted

and patients are not always aware of teaching

activities.(16)

The Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya

sends students to general practices during their

fourth year. They learn by observing doctor

patient encounters, taking histories, performing

clinical examinations and getting involved with

the management of patients with the GP teacher.

The doctor student interaction usually takes

place in English which is the medium of medical

education in the country.

Although studies from the western world have

revealed the positive attitude of patients towards

presence and involvement of students during

the consultation, this area remains relatively

unresearched in Sri Lanka and the south Asian

region. The only reported study from Sri Lanka

in this regard also supported the acceptance

of students by the patients but this study has

been conducted in a non fee levying university

family practice.(17)

Therefore this multicentre study was planned

to explore attitudes of patients towards students

in fee levying general practices.

This descriptive cross sectional study was conducted

in 6 general practices purposively selected to

represent urban and semi-urban practices as well

as general practices managed by both male and

female doctors. A self administered questionnaire

was used to gather demographic data, number of

previous consultations with student participation

and their willingness to have presence of students

at different stages of the consultation, reasons

for the willingness, the factors impacting upon

willingness, patients' experience of consultations

in the presence of students and their views on

consent and confidentiality. Fifty consecutive

eligible patients who consulted the doctor in

the presence of students were invited to respond

to the questionnaire. Patients below 16 years,

seriously ill patients, and confused or cognitively

impaired patients, who were unable to read and

write, were excluded. Younger patients were excluded

since they may not be able to respond to the questionnaire

and the opinion of the guardian could vary depending

on the relationship to the patient.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from

the ethical review committee of the faculty of

medicine, University of Kelaniya.

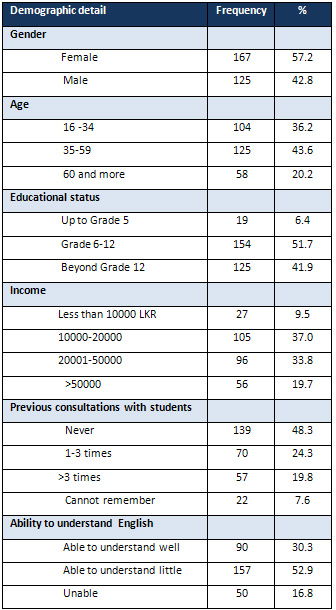

A total of 300 patients responded to the questionnaire.

Table 1: Demographic details of the patients

n=300 note: Percentages expressed are of valid

responses for a given item, not for the entire

sample

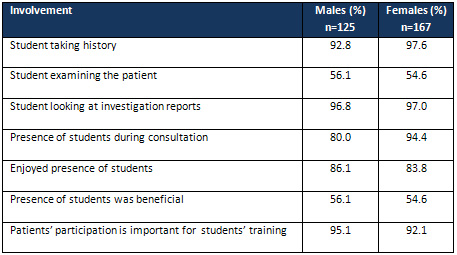

Table 2: Patients' agreement on involvement

of students

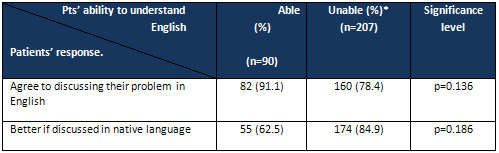

Patients' opinion on discussing their problems

in English

Overall 81.7% agreed with the doctor discussing

their problem in English with students, while

77% felt it was better if the discussion took

place in their native language. More people

among those who could not understand English

preferred if discussions took place in their

native language.

Table 3: Patients' attitudes towards discussion

in English vs their knowledge of English

*able to understand little + unable to understand

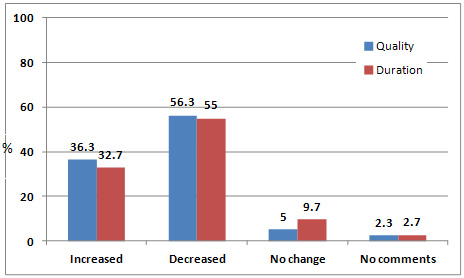

Graph 1: Patients' perception on the impact

of presence of students on quality & duration

of consultation

Only 14.3% of the patients were unhappy about

having to spend more time during consultation

due to the involvement of students. 75.5% were

not bothered while 10.2% did not respond to

the question.

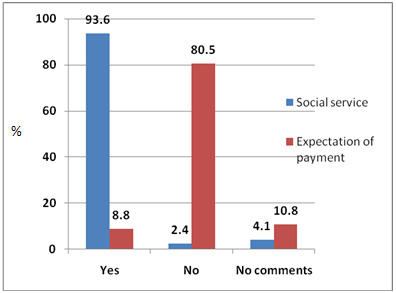

Graph 2: Patients' opinion on involvement

of training and expectation of a payment

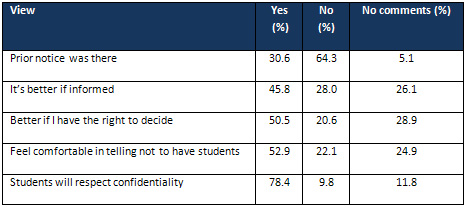

Table 4: Patients' views on consent and

confidentiality

Patients' views on number of student participation

during consultation

17.1% of the patients preferred the presence

of one student while 29.0% preferred 2 students.

Another 23.9% preferred 3 and 30% agree with

the presence of more than 3 students.

For this multicenter study general practices were

purposively selected to include general practices

with different backgrounds with the objective

of obtaining views of a wide range of patients.

Analysis of their demographic details shows that

the sample included both males and females, patients

belonged to all age groups, and different socioeconomic

and educational backgrounds. It also included

patients who had previous experience with students

and those who had not consulted the doctor in

the presence of students.

The vast majority of patients had positive feelings

about the involvement of medical students. More

than 90% of the patients were willing to tell

details of the disease to students but only about

50% agreed to be examined by a student. There

was no significant difference in attitudes between

males and females. There was no resistance to

students looking at their investigation reports

and the majority not only agreed to presence of

students during consultation, they enjoyed interaction

with students as well. Quite rightly patients

have understood that their participation is important

for student training. Number of previous studies

also reported high consent rate to presence or

participation of students in general practices.(18,19,20)

Our finding that patients were less willing to

be examined by a student was also in line with

reported studies. (16,21,)

This study explored views of patients on doctor

student interaction taking place in English

which is not the native language of the country.

Only 30.3% of the participants could understand

English language well according to them. Even

though they agreed to doctor student interaction

in English they preferred if discussions took

place in their native language. Studies conducted

in western countries where the medium of learning

and the mother tongue of patients were the same

revealed that patients enjoyed hearing their

condition being discussed with the students

(22), drew more information from the explanation

directed at students and discussions with students

led to increased insight into clinical reasoning.(23)

Such benefits cannot be expected for patients

in Sri Lankan settings and even could have unwarranted

effects such as misunderstandings in patients

which could create unnecessary anxiety. Therefore

GP teachers should either discuss with students

in native language or offer an explanation to

patients afterwards. It is important not to

sideline patients in discussions and a sense

of inclusion and participation is essential

for patient satisfaction with the experience.

(24)

The perception among patients that the quality

of the consultation was not adversely affected

due to the presence of students by the majority

(92.6%) is an encouragement to GP trainers.

In fact about one third felt there was a positive

impact perhaps due to more detailed history

taking, methodical examination and plan of management

and doctor spending more time with the patient

due to the presence of students. The findings

regarding quality of consultation of this study

are in line with previous studies which reported

no decreased sense of patient enablement or

satisfaction(25,26) and even a positive effect.(26,27,28)

32.7 percent thought the duration of the consultation

was more when students were present but the

majority (74%) was not unhappy and willing to

sacrifice their time.

It is heartening to note that the majority of

the respondents were of the view that their

involvement in undergraduate training is a social

service and did not expect a payment for their

involvement and contribution. The probable reasons

may be sense of altruism, mutual obligation

and giving something back to the system.(24,29)

Patients' opinion on the number of students

they would like to interact with at a time varied.

When deciding on the number of students the

space in the consultation room also should be

taken into account. If the room is overcrowded

patients may not feel free to divulge information

and feel embarrassed during examination. It

can create problems for the doctor in managing

patients and for students such an environment

may not be conducive for learning. More students

could compromise one of the key advantages of

community based learning which is the one to

one supervision and the attention of the trainer.

According to patients only 30.6% were aware

that students would be present during the consultation

which is not a satisfactory situation. A fairly

high percentage thought it would have been better

if they were informed beforehand. It is interesting

to note that half the patients felt that they

should be given the choice to decide. Studies

elsewhere in the world have revealed that patients'

consent to participation in medical education

is often taken for granted and formal consent

is not obtained prior to their involvement in

teaching.(16) It is only 52.9% who felt comfortable

in telling the doctor not to have students.

Patients may feel pressured to consent to the

students' presence and they may be concerned

that refusal to have students may disappoint

their family doctor. There is evidence that

patients may have difficulty refusing consent(26)

and GPs should be mindful of this fact.

Patients were of the view that students will

respect the confidentiality of the information

they receive from patients. In one study patients

expressed concern that students would talk about

them afterwards.(30) Students should be strictly

instructed not to discuss about patients in

a careless manner.

Issue of consent and confidentiality should

be an integral part of teaching in both primary

and secondary care and patients should be explained

the need of their participation in teaching

and advantages and disadvantages of participation

of students. Patients should be made aware that

they have the freedom to choose and their non

involvement will in no way influence the care

they receive or the doctor patient relationship.

Patient information can be made available in

the waiting room and consulting rooms to reiterate

that patients have a choice about presence of

students.

This study which demonstrates the views of

a broad range of patients reveals the positive

attitudes of patients and their willingness

to participate in student training which is

vital for the sustainability of community-based

teaching.(31) The findings of this study will

be reassuring for doctors who presently are

involved and those who plan to be involved in

undergraduate training in the future. It will

be of help in planning general practice clerkships.

1. Patients are a willing resource for

student education in training practices.

2. Patients perceive that presence of students

does not decrease the quality of consultation.

3. Patients should be able to choose when

they want to be involved in teaching.

4. Trainers should be careful when discussing

with students in a language not understood by

the patient and at least a brief explanation should

be provided to the patient on what was discussed

1. Boaden N, Bligh J.

Community based medical

education. London: Arnold.

1999;29-41

2. General Medical Council.

Tomorrow's Doctors: Recommendations

on Undergraduate Medical

Education. London: GMC,1993.

3. Marley J. Family medicine

in the 21st century. Sri

Lankan Family Physician

1998;21:22-23

4. Metcalfe D. Family

Medicine: in from the

periphery in medical education.

Sri Lankan Family Physician

1999: 22(1); 3-7.

5. Ramanayake RPJC. Historical

evolution and present

status of family medicine

in Sri Lanka. Journal

of family medicine and

primary care 2013:2;131-134

6. Institute for the Future.

Health and health care,

2010, the forecast, the

future, the challenge.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass,

2000;6-8.

7. Towle A. Community

based teaching. Sharing

ideas 1. London: King's

Fund Centre; 1992.

8. Parle JV, Greenfield

SM, Skelton J, Lester

H, Hobbs FD. Acquisition

of basic clinical skills

in the general practice

setting. Med Educ 1997;31:99-104.

9. Oswald NT. Teaching

clinical methods to medical

students. Med Educ 1993;27:351-

4.

10. Murray E, Jolly B,

Model M. Can students

learn clinical method

in general practice? A

randomized crossover trial

based on objective structured

clinical examinations.

Br Med J 1997;315:920-3.

11. Berg D. Sebastian

J, Heudebert G. Development,

Implementation and evaluation

of an advanced physical

diagnosis course for senior

medical students. Acad

Med 1994;69:758-64.

12. Lefford F, Mccroriet

P, Perrins F. A survey

of medical undergraduate

community-based

teaching: taking undergraduate

teaching into the community.

Medical Education 1994;28:

312-315

13. Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt

D, Kutob R. 2003. Factors

related to the choice

of family medicine: A

reassessment and literature

review. J Am Board Fam

Pract 2003; 16(6):502-12.

14. Mol SSL, Peelen JH,

Kuyvenhoven MM. Patients'

views on student participation

in general practice consultations:

A comprehensive review.

Medical teacher 2011;33:e397-e400

15. Wright HJ. Patients'

Attitudes to Medical Students

in General Practice. BMJ

1974;1: 372-6.

16. Monnickendam SM, Vinker

S, Zalewski S , Cohen

O, Kitai E. Patients'

Attitudes Towards the

Presence of Medical Students

In Family Practice Consultations.

IMAJ 2001; 3:903-906 .

17. Ramanayake RPJC, Sumathipala

WLAH, Rajakaruna IMSM,

Ariyapala DPN. Patients'

Attitudes Towards Medical

Students in a Teaching

Family Practice: A Sri

Lankan Experience. Journal

of Family Medicine and

Primary Care 2012 ; 1

(2): 122-126

18. Choudhury TR, Moosa

AA ,Cushing A, Bestwick

J. Patients' attitudes

towards the presence of

medical students during

consultations. Med Teach

2006 ;28(7): e198-203

19. Haffling AC, Hakansson

A. 2008. Patients consulting

with students in general

practice: Survey of patients'

satisfaction and their

role in teaching. Med

Teach 30: 622-629.

20.Hudson JN, Weston KM,

Farmer EE, Ivers RG, Pearson

RW. 2010. Are patients

willing participants in

the new wave of community-based

medical education in regional

and rural Australia? Med

J Aust 192(3):150-153.

21. Salisbury K, Farmer

EA, Vnuk A. Patients'

views on the training

of medical students in

Australian general practice

settings. Australian Family

Physician 2004;33(4):281-283

22. Grant A, Robling M.

Introducing undergraduate

medical teaching into

general practice: an action

research study. Medical

teacher 2006; 28: 7:e192-e197

(doi:10.1080/01421590600825383)

23. Sturman N. Teaching

medical students Ethical

challenges. Aust Fam physician

2011;40(12):992-995

24. Sweeney K, Magin P,

Pond D. Patient attitudes:

training students in general

practice. Aust Fam Physician

2010;39:676-82

25. Benson J, Quince T,

Hibble A, Fanshawe T,

Emery J. Impact on patients

of expanded, general practice

based, student teaching:

observational and qualitative

study. BM J 2005;331:89.

doi: 10.1136/bmj.38492.599606.8F

26. Price R, Spencer J,

Walker J. Does the presence

of medical students affect

quality in general practice

consultations? Med Educ

2008;42:374-81.

27. Cooke F, Galasko G,

Ramrakha V, Richards D,

Rose A, Watkins J. Medical

students in general practice:

how do patients feel?

BM J 1996;46:361-2.

28. Holden J, Pullon S.

Trainee interns in general

practices. N Z Med J 1997;110:377-9.

29. Coleman K, Murray

E. Patients' views and

feelings on the community-based

teaching of undergraduate

medical students: a qualitative

study. Family Practice

2002;19: 2:183

30. O'Flynn N, Spencer

J, Jones R. Consent and

confidentiality in teaching

in general practice: survey

of patients' views on

presence of students.

BMJ 1997; 315: 1142.

31. Rod Pearce, Caroline

O Laurence, Linda E Black,

Nigel Stocks. The challenges

of teaching in a general

practice setting. MJA

2007:187;129-132

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|