|

|

|

| ............................................................. |

|

|

| ........................................................ |

| From

the Editor |

|

Editorial

A. Abyad (Chief Editor) |

|

|

|

|

........................................................ |

Special

Education feature - Part 2

........................................................

Research

........................................................

Case Report

........................................................

Education Review

|

Middle

East Quality Improvement Program

(MEQUIP QI&CPD)

|

|

Chief

Editor -

Abdulrazak

Abyad

MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF, AFCHSE

.........................................................

Editorial

Office -

Abyad Medical Center & Middle East Longevity

Institute

Azmi Street, Abdo Center,

PO BOX 618

Tripoli, Lebanon

Phone: (961) 6-443684

Fax: (961) 6-443685

Email:

aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Publisher

-

Lesley

Pocock

medi+WORLD International

11 Colston Avenue,

Sherbrooke 3789

AUSTRALIA

Phone: +61 (3) 9005 9847

Fax: +61 (3) 9012 5857

Email:

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

Editorial

Enquiries -

abyad@cyberia.net.lb

.........................................................

Advertising

Enquiries -

lesleypocock@mediworld.com.au

.........................................................

While all

efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy

of the information in this journal, opinions

expressed are those of the authors and do not

necessarily reflect the views of The Publishers,

Editor or the Editorial Board. The publishers,

Editor and Editorial Board cannot be held responsible

for errors or any consequences arising from

the use of information contained in this journal;

or the views and opinions expressed. Publication

of any advertisements does not constitute any

endorsement by the Publishers and Editors of

the product advertised.

The contents

of this journal are copyright. Apart from any

fair dealing for purposes of private study,

research, criticism or review, as permitted

under the Australian Copyright Act, no part

of this program may be reproduced without the

permission of the publisher.

|

|

|

| November 2016

- Volume 14, Issue 9 |

|

|

CME Needs Assessment:

National Model - Dental CME

Abdulrazak

Abyad (1)

Ninette Bandy (2)

(1) Abdulrazak Abyad, MD, MPH, MBA, AGSF

(2) Ninette Banday, BDS, MPH, DMSc, FICOI,FICD

Correspondence:

Dr Abdulrazak Abyad

Email: aabyad@cyberia.net.lb

This

CME Needs Assessment paper was written to provide

analysis on a particular regional country’s

<<the country>> proposed CME in

Primary Care program. It has been provided as

a National Model that other countries may wish

to replicate.

In

this new millennium most nations, both developed

and developing are actively reviewing national

health policies and strategies as well as health

delivery systems. The over-riding imperative

in all cases is to deliver quality health care

in a cost efficient manner while addressing

issues of access and equity.

The provision of

health services in <<the country>>

is divided into federal, local and private sectors.

The Health Authority, and the local government

agency is responsible for the provision of integrated,

comprehensive, and quality of health services

for its population.

As

in

most

areas

of

education,

for

many

years

there

has

been

intense

debate

about

the

definition,

purpose,

validity,

and

methods

of

learning

needs

assessment.

It

might

be

to

help

curriculum

planning,

diagnose

individual

problems,

assess

student

learning,

demonstrate

accountability,

improve

practice

and

safety,

or

offer

individual

feedback

and

educational

intervention.

Published

classifications

include

felt

needs

(what

people

say

they

need),

expressed

needs

(expressed

in

action)

normative

needs

(defined

by

experts),

and

comparative

needs

(group

comparison).

Other

distinctions

include

individual

versus

organizational

or

group

needs,

clinical

versus

administrative

needs,

and

subjective

versus

objectively

measured

needs.

The

defined

purpose

of

the

needs

assessment

should

determine

the

methods

used

and

the

use

made

of

the

findings.

Exclusive

reliance

on

formal

needs

assessment

in

educational

planning

could

render

education

an

instrumental

and

narrow

process

rather

than

a

creative,

professional

one.

| METHODS

OF

NEEDS

ASSESSMENT |

Although

the

literature

generally

reports

only

on

the

more

formal

methods

of

needs

assessment,

doctors

and

dentists

use

a

wide

range

of

informal

ways

of

identifying

learning

needs

as

part

of

their

ordinary

practice.

These

should

not

be

undervalued

simply

because

they

do

not

resemble

research.

Questionnaires

and

structured

interviews

seem

to

be

the

most

commonly

reported

methods

of

needs

assessment,

but

such

methods

are

also

used

for

evaluation,

assessment,

management,

education,

and

now

appraisal

and

revalidation.

The

main

purpose

of

needs

assessment

must

be

to

help

educational

planning,

but

this

must

not

lead

to

too

narrow

a

vision

of

learning.

Learning

in

a

profession

is

unlike

any

other

kind

of

learning.

Doctors

and

dentists

live

in

a

rich

learning

environment,

constantly

involved

in

and

surrounded

by

professional

interaction

and

conversation,

educational

events,

information,

and

feedback.

The

search

for

the

one

best

or

"right"

way

of

learning

is

a

hopeless

task,

especially

if

this

is

combined

with

attempting

to

"measure"

observable

learning.

Research

papers

show,

at

best,

the

complexity

of

the

process.

Multiple

interventions

targeted

at

specific

behavior

result

in

positive

change

in

that

behavior.

Exactly

what

those

interventions

are

is

less

important

than

their

multiplicity

and

targeted

nature.

On

the

other

hand,

different

doctors

and

dentists

use

different

learning

methods

to

meet

their

individual

needs.

For

example,

in

a

study

of

366

primary

care

doctors

who

identified

recent

clinical

problems

for

which

they

needed

more

knowledge

or

skill

to

solve,

55

different

learning

methods

were

selected.

The

type

of

problem

turned

out

to

be

the

major

determinant

of

the

learning

method

chosen,

so

there

may

not

be

one

educational

solution

to

the

identified

needs.

Much

of

a

doctors'

and

a

dentists'

learning

is

integrated

with

their

practice

and

arises

from

it.

The

style

of

integrated

practice

and

learning

("situated

learning")

develops

during

the

successive

stages

of

medical

education.

The

components

of

apprenticeship

learning

in

postgraduate

training

are

made

up

of

many

activities

that

may

be

regarded

as

part

of

practice

(13).

Senior

health

professionals

might

also

recognize

much

of

their

learning

in

some

of

these

elements

and

could

certainly

add

more-such

as

conversations

with

colleagues.

Thus,

educational

planning

on

the

basis

of

identified

needs

faces

real

challenges

in

making

learning

appropriate

to

and

integrated

with

professional

style

and

practice.

The

first

step

is

to

recognize

the

need

of

learning

that

are

a

part

of

daily

professional

life

in

medicine

and

to

formalize,

highlight,

and

use

these

as

the

basis

of

future

recorded

needs

assessment

and

subsequent

planning

and

action,

as

well

as

integrating

them

with

more

formal

methods

of

needs

assessment

to

form

a

routine

part

of

training,

learning,

and

improving

practice.

Quality

health

care

for

patients

is

supported

by

maintenance

and

enhancement

of

clinical,

management

and

personal

skills.

The

knowledge

and

skills

of

practitioners

require

refreshment,

and

good

professional

attitudes

need

to

be

fostered

through

the

process

of

continuing

professional

development.

In

an

attempt

to

assess

the

needs

for

professional

development

of

the

medical,

dental

practitioners

and

nursing

staff

a

survey

was

conducted

by

means

of

a

Questionnaire

(APPENDIX

).

This

report

takes

into

account

a

wide

section

of

the

various

medical,

dental

and

nursing

staff.

The

purposes

of

the

review,

therefore

were

to:

•

Determine

the

area

of

professional

development

•

Help

thehealth

professional

,

meet

the

challenge

of

changes

in

the

structure

and

delivery

of

patient

care.

•

Encourage

more

reflection

on

practice

&

learning

needs,

including

more

forward

planning;

and

•

Make

the

educational

methods

used

in

practice

more

effective

| PART

I-

DEMOGRAPHIC

DATA

(SEE

APPENDIX) |

465

questionnaires

were

included

in

the

study

out

of

600

hundreds

distributed.

The

exclusion

criteria

were

that

either

the

questionnaire

was

not

returned

or

was

incomplete.

The

response

rate

was

77

percent.

The

mean

age

of

the

study

population

was

42years

(SD

9.70)

with

the

minimum

age

being

23

years

and

maximum

being

74years.

72%

of

the

study

populations

were

below

50

years.

The

mean

of

the

number

of

years

since

graduation

was

18

years

(mean

=8.46,

SD=9.16).

Whereas

the

mean

of

the

number

of

years

in

practice

was

17

years

(Mean=17.18,

SD=9.16).

As

for

gender

distribution

35%

of

the

samples

were

males

vs

65%

who

were

females.

| TOPICS

FOR

THE

CME

FOR

DENTISTS

AND

DENTAL

ASSISTANTS

|

The

report

includes

the

details

of

the

ratings

on

various

topics,

however

the

topics

that

received

the

highest

ratings

were:

Infection

control,

management

of

the

medically

compromised

patients,

Diagnosis

&

Treatment

planning,

Dental

radiology

&

its

interpretation,

preventive

dentistry,

dental

composites

and

endodontics.

The

response

rate

for

the

monthly

activity

was

the

highest

with

Hands

-

workshops.

Assessment

Strategies

In

the

implementation

of

any

CME

activities

assessment

strategies

is

critical

to

judge

the

success

of

such

a

program.

For

example

communication

skills

learning

must

be

both

formative

and

summative.

The

knowledge,

skills,

and

attitudes

to

be

assessed

must

be

made

explicit

to

both

learners

and

teachers

alike.

Potential

evaluators

include

local

experts,

course

faculty,

simulated

and

real

patients,

peers,

and

the

learners

themselves.

Formative

assessment

should

occur

throughout

the

communication

skills

curriculum

and

is

intended

to

shape

and

improve

future

behaviors.

Assessment

of

communication

skills

must

include

direct

observation

of

performance.

Evaluation

of

setting

a

therapeutic

environment,

gathering

data

and

providing

information

and

closure

must

be

included.

Evaluation

of

advanced

skills,

including

use

of

interpreters,

providing

bad

news

and

promoting

behavior

change

should

be

done

as

well.

Criteria

should

match

the

novice

level

of

the

end

of

second

year

student,

who

should

be

able

to

identify

the

critical

issues

for

effective

communication

and

perform

the

skills

under

straightforward

circumstances.

Quality

CME

can

enhance

the

knowledge

base

and

practice

skills

of

the

participating

health

care

provider

and

is

increasingly

used

as

part

of

the

credentialing

and

reappointment

process.

Continuing

Medical

Education

is

important

not

only

as

a

requirement

for

practice,

but

as

means

for

the

profession

to

achieve

one

of

its

primary

goals:

QUALITY

PATIENT

CARE.

To

our

patients

CME

requirements

are

a

commitment

made

by

the

medical

and

dental

practitioner

to

keep

our

knowledge

and

skills

current.

CME

really

is

about

changing

behavior

through

education-about

doing

something

different,

doing

it

better."

It

is

critical

to

look

at

CME

and

CPD

in

the

mentality

of

21st

century.

We

attempted

to

clearly

present:

that

the

patient's

concerns,

values

and

outcomes

must

be

the

center

of

care;

that

partnering

with

an

activated

patient

is

essential;

that

self-awareness

is

essential

in

being

an

effective

physician;

that

improving

the

process

of

care

and

health

outcomes

is

the

physician's

responsibility

and

requires

a

systems

approach.

Quality

CME

can

enhance

the

knowledge

base

and

practice

skills

of

the

participating

health

care

provider

and

is

increasingly

used

as

part

of

the

credentialing

and

reappointment

process.

Continuing

Education

is

important

not

only

as

a

requirement

for

practice,

but

as

means

for

the

profession

to

achieve

one

of

its

primary

goals:

QUALITY

PATIENT

CARE.

To

our

patients

CME

requirements

are

a

commitment

made

by

the

medical

and

dental

practitioner

to

keep

our

knowledge

and

skills

current.

|

DENTAL

CARE

EDUCATION

INITIATIVE

|

The

topics

that

were

covered

in

the

survey

included

the

following

CME

FOR

DENTISTS

AND

DENTAL

ASSISTANT

Infection

Control

The

Patient

Management

Skills

Preventive

Dentistry

Restorative

&

Esthetic

Dentistry

Endodontics

Pedodontics.

Periodontics.

Prosthodontics

Oral

Surgery

Implantology

Health

Promotional

Activities

&

Oral

Health

Education

Format

of

CME

Timing

of

the

CME

Type

of

Activities

Self

Study

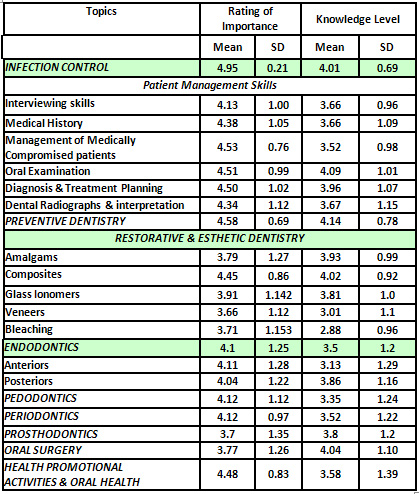

Results

of

Survey

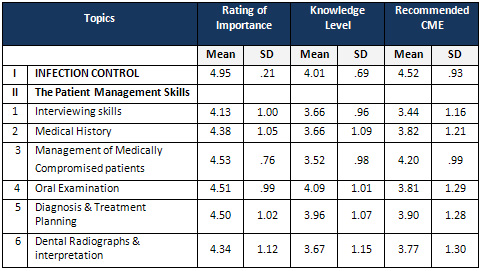

The

response

to

the

various

topics

in

dentistry

is

presented

in

Tables

1-3

.

These

topics

were

rated

similarly

as

the

topics

in

medicine

with:

a)

Order

of

importance

of

the

topic.

(1

=

least

important

to

5

=

most

important)

b)

Rating

your

own

current

level

of

Knowledge/performance.

(1

=

basic

to

5

=

highly

skilled)

c)

Recommend

CME

activity

on

level

of

priority

(1

=

least

to

5

=

highest

priority)

Table

1

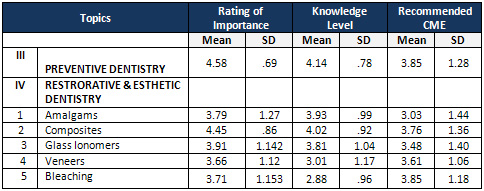

Table

2

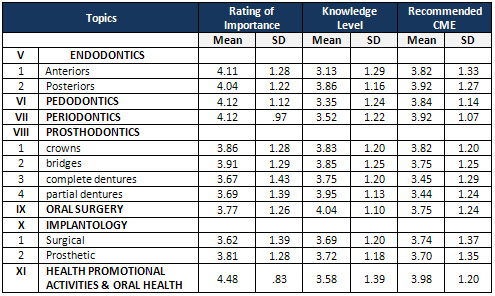

Table

3

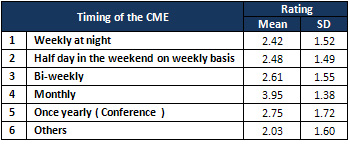

Attempt

was

made

to

establish

the

most

suitable

timings

and

frequency

of

the

CME

activities.

The

ratings

adopted

were

:

1

being

least

appropriate,

5

most

appropriate.

The

results

are

presented

in

Table

4

and

the

need

for

a

monthly

activity

was

rated

highest

3.95

with

Hands-

on

Training

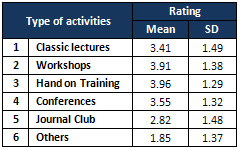

Table

5

Table

4:

Timing

of

CME

Table

5:

Type

of

Activities

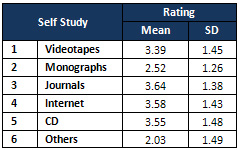

Table

6:

Self

Study

Methods

| OVERALL

EVALUATION

AND

NEED

FOR

IMPROVEMENT

|

As

curricula

and

methodologies

for

the

training

of

physicians

approach

the

100-year

anniversary

of

the

Flexner

report

(2010),

it

is

important

to

recognize

that

medical

education

has

been

a

constantly

evolving

process

to

address

the

training

needs

of

physicians

to

serve

society

and

its

people.

Understanding

curricular

reform

is

one

of

understanding

its

history.

Many

reports

prior

to

1990

(e.g.

Rappleye,

GPEP,

Macy

Foundation)

comment

on

the

process,

as

well

as

the

content

and

structure

of

medical

education.

Several

have

noted

the

glacial

progress

of

reform

and

the

reasons

behind

this

pace.

More

recently

in

the

1990s

and

the

new

century,

the

breadth

of

involved

stakeholders

in

this

process

has

widened,

as

many

entities

within

and

beyond

medical

schools

have

identified

significant

needs

in

the

process

of

education

of

physicians

for

the

21st

century.

These

defined

challenges

reflect

not

only

the

explosion

of

medical

knowledge

and

technology

and

the

changing

demographics

of

the

population,

but

also

the

broader

societal

and

health

care

system

changes

that

are

significantly

affecting

the

contextual

environment

in

which

medicine

is

practiced.

There

is

a

need

to

improve

and

train

people

responsible

for

CME

and

CPD

activities.

Traditional

educational

practice

in

medical

schools

emphasize

the

organ

systems

and

discipline-based

approaches,

but

in

Primary

Health

Care

,

faculty

development

is

necessary

to

ensure

effective

team

teaching

approaches,

interdisciplinary

collaboration,

integration

of

material

across

disciplines

and

courses,

and

focus

on

patient

health

outcomes.

The

integration

of

these

concepts

needs

to

be

across

the

curriculum

and

in

every

course

rather

than

adding

additional

curricular

time.

Faculty

development

in

adult

education

techniques

may

be

necessary.

Faculty

development

for

role

modeling

and

mentoring

techniques

should

be

considered.

The

response

rate

from

the

survey

was

relatively

high,

reflecting

the

interest

of

the

primary

health

care

team

in

CME

and

CPD.

There

are

a

number

of

Barriers

to

obtaining

optimal

CME

including

lack

of

time

and

type

of

activities.

Lack

of

time

Lack

of

time

was

seen

as

the

biggest

barrier

to

obtaining

optimal

CME.

All

CME

was

carried

out

in

personal

time.

'It

means

night-time

or

weekends.

CME

activity

has

to

fit

in

with

on

call

and

family.

'I

am

a

working

mother,

time

is

the

essence.'

In

our

survey

(table

6)

most

health

care

members

preferred

CME

activity

on

a

monthly

basis

which

reflects

that

time

is

precious

for

the

busy

health

professionals.

Motivation

and

fatigue

were

other

barriers

to

CME.

Distance,

availability

and

cost

were

seldom

raised

as

issues

for

urban

GPs.

However,

distance

precluded

attendance

for

many

rural

practitioners,

as

did

difficulty

obtaining

locums,

cover

for

single

days,

availability

of

CME

and

financial

considerations.

The

perceived

challenge

was

to

increase

the

accessibility

of

personally-interactive

CME.

A

number

of

studies

have

shown

preference

of

GPs

for

personal

interaction.

Some

studies

have

shown

a

preference

amongst

physicians

for

lectures

but

this

may

include

interaction.

Others

have

found

journals

the

most

popular

source

of

information

but

interactive

formats

were

still

highly

rated.

Preference

depends

on

the

type

and

quality

of

personal

experience

of

this

type

of

format.

Pendleton

differentiated

the

academic

and

professional

approach

to

CME.

He

postulated

that

the

academic

prefers

the

written

medium

and

the

clinician

prefers

face-to-face.

In

our

survey

the

respondents

preferred

the

most

hand

on

training,

workshop,

and

conferences.

Review

of

randomized

controlled

trials

on

CME

interventions

revealed

that

personal

interaction

to

be

central

to

effectiveness

in

change

in

practice.

Several

studies

have

reported

that

physicians

seek

confirmation

and

validation

of

current

and

new

medical

practices

through

their

peers.

Other

studies

have

confirmed

the

importance

of

interaction

in

changing

professional

behavior.

However,

it

has

not

been

established

which

elements

of

the

interactive

process

enable

learning.

Interaction

allows

for

clarification,

personalisation

of

information,

exploration,

feedback,

and

reflection.

It

can

also

address

other

needs

of

doctors

that

may

not

be

recognized

or

quantified

-

the

need

for

support,

recognition,

motivation

and

fulfillment,

and

the

'need'

to

belong

to

a

professional

community.

As

for

self

study

methods

the

respondent

preferred

mostly

journals

followed

by

the

internet

followed

by

CD

as

shown

in

Table

6.

Interactive

formats

are

not

inherently

beneficial

nor

always

produce

change.

Some

formats

may

be

more

conducive

to

specific

changes

in

behavior

and

some

to

support.

Group

dynamics,

facilitation,

personal

agendas,

and

internal

and

external

influences

contribute

to

the

complexity

of

the

format.

In

general,

the

focus

was

on

choice

of

CME

as

opposed

to

other

elements

of

the

learning

cycle.

This

approach

has

been

documented

previously

and

reflects

the

traditional

approach

to

learning.

It

is

well

established

that

CME

should

follow

the

principles

of

androgogy

-

adult,

self-directed

learning.

The

term

'androgogy'

has

been

coined

to

describe

the

learning

culture

appropriate

to

adult

education

.

Whereas

the

term

'pedagogy'

describes

the

teacher-centred

approach

to

the

education

of

children,

androgogy

'recognises

education

to

be

a

dynamic

lifelong

process'

that

'is

learner-orientated'.

This

is

grounded

in

experiential

learning

-

identifying

and

addressing

needs

and

applying

learning

with

continuing

reflection.

Although

much

has

been

written

about

the

theory

and

benefits

of

this

model.

GPs

do

not

appear

to

adopt

it.

This

is

not

unique

to

GPs

-

a

study

of

physicians'

CME

found

that

'unstructured

ad

hoc

reading

and

postgraduate

activities

predominate

over

methods

based

on

specific,

individual

needs

or

on

current

patient

problems'.

Some

GPs

in

our

study

did

recognise

that

tailoring

their

CME

to

their

identified,

specific

needs

was

better

than

the

opportunistic

approach,

but

few

attempted

this

in

any

structured

way.

Discussions

with

colleagues

one-to-one

and

in

small

groups

may

serve

as

an

informal

process

of

reflection,

even

though

the

benefits

may

not

be

easily

quantifiable.

The

process

of

reflecting

on

issues,

debating

problem

areas

and

formalising

opinions

may

be

helpful

to

the

clinician,

even

where

there

has

not

been

a

specific

updating

of

knowledge.

CME

Needs

for

Dentistry

The

topic

of

Infection

Control

received

the

highest

ratings

of

all

the

topics

4.95

(SD

0.21)

rating

for

and

a

rating

of

4.01

(SD

0.69)

for

knowledge

level.

The

topic

of

implantology

was

rated

high

for

level

of

importance,

but

received

lowest

scores

for

knowledge

level

2.8

(SD

1.2).

This

reflects

the

fact

that,

until

recently

this

topic

was

not

taught

as

part

of

the

curriculum

in

the

study

of

under

graduate

dentistry.

Hence

many

general

practitioners

lack

adequate

knowledge

and

information

on

this

topic.

In

addition

as

they

are

not

practicing

this

specialty

it

was

rated

as

the

topic

of

'least

important'.

Also

management

of

the

medically

compromised

patients

was

rated

of

high

importance

with

a

score

of

4.53

(SD

0.76)

with

the

least

score

for

current

level

of

knowledge

of

the

topic

3.52

(SD

0.98).

An

area

that

needs

to

be

focused

on.

The

details

of

the

various

topics

that

were

considered

is

presented

in

Table

9.

Table

9:

Topics

considered

in

the

CME

Survey

Questionnaire

for

Dentistry

Both

Amalgams

and

glass

ionomer

restorations

were

rated

low

for

importance

as

well

as

knowledge

level

because

composites

is

the

materials

which

is

being

predominantly

used

for

restorations.

Interestingly

both

the

topics

that

is

veneers

and

bleaching

received

low

scores

for

level

of

importance

as

well

as

knowledge

level

probably

because

these

procedures

are

not

being

practiced

in

the

GAHS

dental

facilities

in

the

Primary

Health

Care

Center

dentists

who

comprised

the

major

proportion

of

the

study

population.

Response

to

the

timing

of

the

CME

activity

was

highest

for

a

monthly

event

3.95

(SD

1.38)

while

the

hands

-

on

Training

activity

was

highly

recommended

3.96

(SD

1.29).

For

the

mode

of

self

directed

learning

Journals

were

rated

high

3.64

(SD

1.38).

Quality

CME

can

enhance

the

knowledge

base

and

practice

skills

of

the

participating

health

care

provider

and

is

increasingly

used

as

part

of

the

credentialing

and

reappointment

process.

Continuing

Medical

Education

is

important

not

only

as

a

requirement

for

practice,

but

as

means

for

the

profession

to

achieve

one

of

its

primary

goals:

QUALITY

PATIENT

CARE.

To

our

patients

CME

requirements

are

a

commitment

made

by

the

medical

and

dental

practitioner

to

keep

our

knowledge

and

skills

current.

In

the

implementation

of

any

CME

activities

assessment

strategies

is

critical

to

judge

the

success

of

such

a

program.

For

example

communication

skills

learning

must

be

both

formative

and

summative.

The

knowledge,

skills,

and

attitudes

to

be

assessed

must

be

made

explicit

to

both

learners

and

teachers

alike.

Potential

evaluators

include

local

experts,

course

faculty,

simulated

and

real

patients,

peers,

and

the

learners

themselves.

Formative

assessment

should

occur

throughout

the

communication

skills

curriculum

and

is

intended

to

shape

and

improve

future

behaviors.

This

requires

direct

observation

(in

person

or

videotaped)

of

the

skills

during

role-play

activities,

with

standardized

patients,

and

with

real

patients.

The

feedback

provided

should

be

balanced

and

nonjudgmental.

Self-assessment

during

the

learning

process

should

be

encouraged.

Assessment

of

communication

skills

must

include

direct

observation

of

performance.

Evaluation

of

setting

a

therapeutic

environment,

gathering

data

and

providing

information

and

closure

must

be

included.

Evaluation

of

advanced

skills,

including

use

of

interpreters,

providing

bad

news

and

promoting

behavior

change

should

be

done

as

well.

Criteria

should

match

the

novice

level

of

the

end

of

second

year

student,

who

should

be

able

to

identify

the

critical

issues

for

effective

communication

and

perform

the

skills

under

straightforward

circumstances.

Specific

tools

can

be

chosen

from

among

the

following:

•

Standardized

patients

•

OSCE's

•

Observed

performance

with

patients

and

others

•

Written

reflections

describing

how

a

learner

would

approach

a

certain

situation

•

MCQ's

Adult

Learning

Principles

In

addition

to

being

"champions,"

teachers

need

to

employ

principles

of

adult

learning

in

their

approach

to

teaching

these

topics.

The

knowledge

base

for

any

of

these

topics

is

changing

every

day

with

the

information

and

technology

explosion

that

has

occurred

in

the

last

quarter-century.

Genetics

is

a

perfect

example

of

a

topic

subject

to

rapid,

ongoing

revision

based

upon

new

research

findings.

Physicians

must

learn

how

to

identify

their

own

learning

needs

and

address

these

needs

effectively,

in

order

to

keep

up

with

the

ever-advancing

knowledge

base

in

most

of

these

topic

areas.

Self-Awareness

In

addition

to

fostering

an

enthusiastic

approach

to

lifelong

learning,

the

instructional

method

must

encourage

physicians

to

reflect

upon

their

own

lives

in

relationship

to

the

topic.

The

topic

of

geriatrics,

for

example,

emphasizes

many

issues

that

every

student

will

face,

through

the

aging

of

parents

and

themselves.

Substance

abuse,

end-of-life,

and

other

topics

often

elicit

strong

emotions

within

students,

as

physicians

remember

past

experiences

or

recognize

ongoing

struggles

within

their

own

lives.

Teachers

must

create

environments

that

are

safe

enough

to

foster

trust

and

intimacy,

and

yet

challenge

physicians

to

reflect

upon

their

own

experience

of

life,

as

they

develop

a

basic

level

of

mastery

in

these

special

topic

areas.

"CME

really

is

about

changing

behavior

through

education-about

doing

something

different,

doing

it

better."

The

bottom

line

of

CME

in

the

past

has

been

the

activities

we

produced-how

many,

how

much

they

cost,

how

many

people

came.

In

essence,

CME

was

more

activity-oriented

than

learner-oriented.

"Not

only

do

you

have

to

focus

on

the

learner,"

"you

have

to

focus

on

the

learner

in

the

context

in

which

they

are

learning,

which

is

the

healthcare

environment

where

they

practice

medicine."

The

aim

of

the

proposal

is

to

'to

provide

leadership

in

the

delivery

of

high

quality

education,

for

the

primary

care

team,

in

the

context

of

a

caring

and

vibrant

academic

environment'

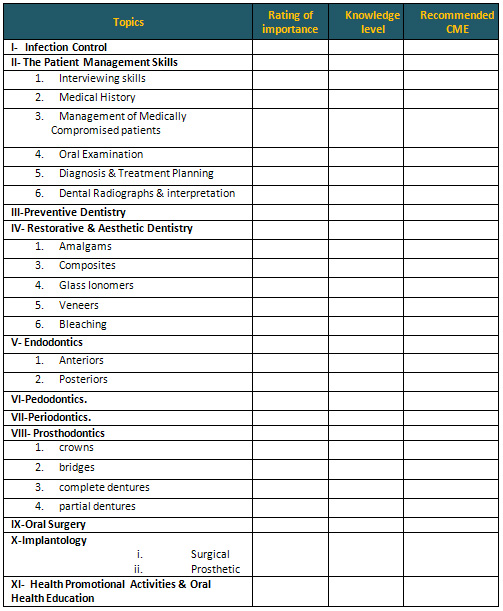

QUESTIONNAIRE:

CME

FOR

DENTISTS

AND

DENTAL

ASSISTANT

Please

rate

each

skill

below:

d)

In

order

of

importance

for

you

to

acquire

or

possess.

(1

=

least

important

to

5

=

most

important)

e)

By

rating

your

own

current

level

of

performance.

(1

=

basic

to

5

=

highly

skilled)

f)

Recommend

CME

activity

on

level

of

priority

(1

=

least

to

5

=

highest

priority)

Any

other

skills

or

topic

you

feel

are

important

for

your

academic

development:

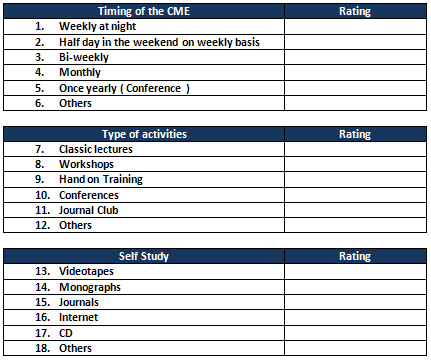

FORMAT

OF

CME

In

order

of

preference

rate

the

below

activities

from

1

to

5

1

being

least

appropriate,

5

most

appropriate

Personal

Information

(optional)

Name

___________________________

Degree

___________________________

E-mail

___________________________

Work

place

_______________________

Are

you

willing

to

help

in

the

teaching

process

of

the

CME

|

|

.................................................................................................................

|

| |

|