Knowledge,

Attitude, Practice And Barriers Of Effective Communication

Skills During Medical Consultation Among General

Practitioners National Guard Primary Health Care

Center,Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Basmah

Saleh Al-Zahrani (1)

Maryam Fahad Al-Misfer (2)

Ali Mohsen Al-Hazmi (3)

(1) Dr. Basmah Saleh Al-Zahrani, MMBS, SB-FM,

AB-FM

Senior registrar , Family Medicine Unit , King

Khalid University Hospital

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

(2) Dr. Maryam Fahad Al-Misfer, MMBS, SB-FM,

AB-FM

Assistant trainer and Senior registrar

Department of Family and Community Medicine,

King Khalid University Hospital

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

(3) Dr.Ali Mohsen Al-Hazmi

Consultant and Assistant professor

Deprtment of Family and Community Medicine,

King Khalid University Hospital

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence:

Dr.Maryam Fahad Al-Misfer

MMBS, SB-FM, AB-FM

Assistant trainer and Senior registrar

Department of Family and Community Medicine,

King Khalid University Hospital

Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Email:

mfalmisfer@yahoo.com

|

Abstract

Objectives:To assess barriers,

practice attitude and knowledge of primary

health care physicians about communication

skills during medical consultations in

primary health care centers in National

Guard Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Design:

Cross sectional study

Methodology:

The study was conducted during the

period from November 2009 till July 2010.

Seventy primary care physicians answered

a structured questionnaire about their

knowledge, practice and barrier of effective

communication skills during medical consultations.

Results:

Survey of 70 PHC physicians showed 25(35.7%)

residents, 28(40%) specialized. The majority

of the physicians did receive some form

of training for communication skills (85.7%),

however, they did perceive lack of proper

training (68.5%) as a barrier also. Common

patient barriers to better communication

with patients were different cultural

norms from physicians or different gender

(51.4%). A system related barrier noted

by physicians was lack of time (82.8%).

Mean score of practicing communication

skills was 37.2/60 and mean knowledge

score was 3.31/6 for the physicians in

our study. No relationship between knowledge

and practice was noted in our study but

a positive correlation between age, years

of experience and practicing communication

skills was found ( F-statistic 5.6, p

value 0.006). Practice scores were significantly

different for residents, staff physicians

and specialists. Physicians who were confident

of their communication skills and who

made a concious effort to apply the skills

that they had learned were shown to score

better on practicing these communication

skills, Chi-sq 30.11 p value <0.001,

and Chi-sq. 12.67 p value 0.002, respectively.

Conclusion:

Knowledge of communication skills

can improve with training however having

the knowledge does not affect the practice

of communication skills unless the physician

is self-confident and has the right attitude

of consciously applying that knowledge

in his/her practice and improvement comes

with age and experience.

Key words:

communication skills, barrier, practice,

knowledge, atittude , primary health care

physicians.

|

The expectations of the public from health

care providers have increased over the last

few decades and the majority are familiar with

their rights in the health care system. As a

consequence, it is of high priority that health

care providers have effective communication

skills. It has been well documented that the

doctor-patient relationship is central to the

delivery of high quality medical care. It has

been shown to affect patient satisfaction, to

decrease the use of pain killers, to shorten

hospital stays, to improve recovery from surgery

and a variety of other biological, psychological

and social outcomes [1-4].

Good communication skills are integral to medical

and other healthcare practice. Communication

is important not only to professional-patient

interaction but also within the healthcare team.

The benefits of effective communication include

good working relationships and increased patient

satisfaction. Effective communication may increase

patient understanding of treatment, improve

compliance and lead to improved health outcomes.

It can also make the professional-patient relationship

a more equitable one. Undoubtedly however, there

are barriers to effective communication ranging

from personal attitudes, to the limitations

placed on doctors by the organizational structures

in which they work [5].

In order to deliver effective healthcare, doctors

are expected to communicate competently both

orally and in writing with a range of professionals,

managers, patients, families and carers. Simply

recognizing the need for good communication

skills is not enough; healthcare professionals

must actively strive to achieve good communication

skills by evaluating their own abilities. Education

providers need to ensure that appropriate and

effective training opportunities are available

to doctors to develop and refine such skills

in order to facilitate interaction with patients

and others [5].

Benefits of good communication can be identified

for both doctors and patients.

Benefits for patients

• The doctor-patient relationship is improved.

The doctor is better able to seek the relevant

information and recognize the problems of the

patient by way of interaction and attentive

listening. As a result, the patient's problems

may be identified more accurately [6].

• Good communication helps the patient

to recall information and comply with treatment

instructions thereby improving patient satisfaction

[7, 8]

• Good communication may improve patient

health and outcomes. Better communication and

dialogue by means of reiteration and repetition

between the doctor and patient has a beneficial

effect in terms of promoting better emotional

health, resolution of symptoms and pain control

[9].

• The overall quality of care may be improved

by ensuring that patients' views and wishes

are taken into account as a mutual process in

decision making.

• Good communication is likely to reduce

the incidence of clinical error [6]

Benefits for doctors

• Effective communication skills may relieve

doctors of some of the pressures of dealing

with the difficult situations encountered in

this emotionally demanding profession. Problematic

communication with patients is thought to contribute

to emotional burn-out and low personal accomplishment

in doctors as well as high psychological morbidity

[10]. Being able to communicate competently

may also enhance job satisfaction.

• Patients are less likely to complain

if doctors communicate well. There is, therefore,

a reduced likelihood of doctors being sued.

In all doctor-patient interactions a variety

of communication skills are required for different

phases of the consultation. During the start

of a consultation, doctors must establish a

rapport and identify the reasons for the consultation.

They must go on to gather information, structure

the consultation, build on the relationship

and provide appropriate information [11]. There

is a trend in healthcare on pushing the need

for strong communication skills in medicine.

In relation to communication with patients,

an increasing focus on shared decision making

and communication of risk, are two of the most

important factors [12]. For example, communication

skills can help healthcare staff to explain

the results of epidemiological studies or clinical

trials to individual patients in ways that can

help patients to understand risk [13]. Doctors

can do this more effectively if they develop

relationships with their patients and if they

take into account knowledge and perceptions

of health risks in the general public [14].

Recent research shows that poor communication

between healthcare staff and patients is still

all too common. For example, when the Lothian

Hospitals NHS Trust in Scotland asked patients

for their views on communication issues, they

found that 60 per cent of patients complained

about a lack of involvement in decisions about

their care, 33 per cent said they had been given

no explanation of test results and 31 per cent

said they had no opportunity to talk to the

doctor. Twenty-three per cent complained of

nurses and doctors saying different things [6].

The General Medical Council (GMC) in London

stresses the need for communication skills in

a number of its guidance notes [15-18]. The

GMC recognizes that the communication skills

required throughout a doctor's career are likely

to change. Doctors should review their skills

as part of their continuing professional development,

and take part in educational activities as a

means of maintaining and further developing

their competence [16].

Other medical professional bodies have highlighted

the importance of communication skills and instituted

various approaches for communication skills

education.

Examples of professional endorsement of the

importance of communication skills for doctors:

• Publications from medical organizations,

such as the BMA's board of medical education

report on communication skills and continuing

professional development (1998) [19] and the

Royal College of Physicians' publication Improving

communication between doctors and patients (1997),

[20] have highlighted the importance of communication

skills.

• The General Medical Council's Professional

Linguistic and Assessment Board (PLAB) examination

has separated its language and communication

elements with the latter being assessed through

role play.

• The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges,

in its recommendations for general professional

training, includes communication skills among

the generic skills required of all trainees.

• Royal Colleges include communication

skills assessment in their training. For example,

the Royal College of General Practitioners has

developed formal mechanisms using video recordings

for assessing communication skills in candidates

[3]. The Royal College of Physicians has introduced

communication skills assessment into its training.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists includes

communication skills in both the basic higher

specialist training curricula and in the Part

3 MRCOphth examination.

• The London Deanery and NHS London have

developed an online interactive educational

program in communication skills for healthcare

professionals, including postgraduate doctors

undertaking the foundation years of training:

www.healthcareskills.nhs.uk.

The potential of communication skills education

There is substantial evidence that communication

skills can be taught, particularly using experiential

methods [21].

To be effective, communication skills teaching

should include [7]:

• Evidence of current deficiencies in communication,

reasons for them, and the consequences for patients

and doctors

• An evidence base for the skills needed

to overcome these deficiencies

• A demonstration of the skills to be learnt

• An opportunity to practice the skills

under controlled and safe conditions

• Constructive feedback on performance

and reflection on the reasons

The potential of communication skills education

There is substantial evidence that communication

skills can be taught, particularly using experiential

methods [21].

To be effective, communication skills teaching

should include [7]:

• Evidence of current deficiencies in communication,

reasons for them, and the consequences for patients

and doctors

• An evidence base for the skills needed

to overcome these deficiencies

• A demonstration of the skills to be learnt

• An opportunity to practice the skills

under controlled and safe conditions

• Constructive feedback on performance

and reflection on the reasons For example, it

has been suggested that most do not include

sufficient information about the training given

to the study participants, making evaluation

difficult [26]. However, there is overwhelming

proof that communication skills in the patient-doctor

relationship can be taught and are learnt [22].

The problem of doctor-patient communication

is more evident in Saudi Arabia for the following

reasons: Firstly, the number of foreign personnel

in health services is rather large [23]. This

workforce communicates with patients and with

one another in a variety of languages different

from the local one. In addition, not much orientation

is given to them on local traditions and the

prevalent health-related beliefs and culture.

Secondly, this manpower deals with a sizeable

sector of consumers, who are themselves expatriate

and speak a variety of languages, and hold health

related traditions and beliefs. This situation

naturally creates a complex environment for

doctor-patient communication. A recent study

from Riyadh [24] alluded to the relationship

between patient satisfaction and doctor-patient

communication. As in other parts of the world,

people in Saudi Arabia are expected to attempt

to find out and understand all aspects of their

health problems [25]. Hence the need to train

and orientate physicians in the skills related

to doctor-patient communication assumes greater

significance. In this regard, several methods

of training, especially for the situation of

Saudi Arabia, can be employed [26-27].

In Saudi Arabia, the acquisition of the skill

of doctor-patient communication hardly exists

in any undergraduate or postgraduate medical

curriculum. There is also paucity of research

in this area. Consequently, it is vital that

comprehensive research be done to clarify the

needs of students and professionals, and outline

the objectives and the modalities of training

in this skill [28].

Research result of study done in KSA, to explore

patient's expectations before consulting their

general practitioners (GPs) and determine the

factors that influence them, showed 74.6% of

the patients preferred Saudi doctors, and 92.6%

would like to have more laboratory tests for

the diagnosis of their illnesses while more

than two thirds of the patients (78.0%) felt

entirely comfortable when talking with GPs about

the personal aspects of their problems and about

half thought that the role of GP was mainly

to refer patients to specialists, while 55.2%

believed that the GP cannot deal with the psychosocial

aspect of organic diseases, and the commonest

reason for consulting GPs was for a general

check up. So, the conclusion was that the GP

has to explore patients' expectations so that

they can either be met or their impracticality

explained. GPs should search for patients' motives

and reconcile this with their own practice.

The GP should be trained to play the standard

role of Primary Care Physician [29].

This

study

attempts

to

explore:

1.

Current

practices

of

communication

skills

of

primary

health

care

physicians

in

health

care

centers

in

National

Guard

Health

Affairs

in

Riyadh.

2.

Main

barriers

that

can

affect

doctor-patient

communications.

3.

Primary

health

care

physicians'

knowledge

about

effective

doctor-patient

communications.

Study

Design:

This

is

a

cross-sectional

study.

Setting:

Held

in

National

Guard

Primary

Health

Care

Centers

in

Riyadh.

Duration

of

Study:

This

study

was

held

during

the

period

from

November

2009

till

July

2010.

Sample

Size:

Seventy

primary

health

care

physicians

participated.

Sampling

Technique:

Survey

questionnaire

was

distributed

to

willing

participants.

Sample

Selection:

All

primary

health

care

physicians

of

different

levels

and

qualifications.

Data

Collection

Procedure:

Data

for

this

study

were

collected

by

questionnaire

which

was

distributed

during

Sunday

morning

professional

education

activity

of

the

department

of

Family

Medicine

and

Primary

Healthcare

in

each

center

for

physicians

and

Half

Day

Release

Course

in

Monday

morning

activity

for

residents.

Data

Collection

Instrument:

Questionnaire

consisted

of

four

sections.

The

first

section

asked

for

physicians'

demographic

data,

educational

items

and

to

rate

their

communication

skills

with

patients.

The

second

section

asked

about

common

barriers

which

can

affect

communication

skills.

The

third

section

asked

about

the

current

practice,

and

the

fourth

asked

about

the

physician's

knowledge

about

communication

skills

by

giving

them

a

sentence

and

asked

about

what

kind

of

skills

that

sentence

indicates.

Ethical

Consideration:

Anonymity

was

maintained

throughout.

The

subjects

received

the

self-administered

questionnaire

with

a

cover

letter

explaining

the

project

and

the

subject's

rights.

The

choice

of

the

items

in

the

questionnaire

was

based

on

the

level

of

communication

skills

a

General

Practitioner

needs.

Data

Analysis

Procedure:

Once

the

data

collection

was

completed,

it

was

checked

and

entered

into

the

computer

using

the

Statistical

Package

for

Social

Sciences

(SPSS),

version

15.

Descriptive

analysis

of

mean,

median

mode,

frequencies

and

percentages

were

carried

out

on

most

of

the

variables,

including,

age,

gender,

self-rating

of

skills,

years

of

experience,

levels

of

experience,

training

history,

communication

skill

practices

and

knowledge

scores.

In

addition,

relationships

were

explored

using

chi-square,

linear

regression,

Kruskal

Wallis

and

Mann

Whitney

where

needed.

A

total

of

70

primary

health

care

physicians

participated

in

the

study.

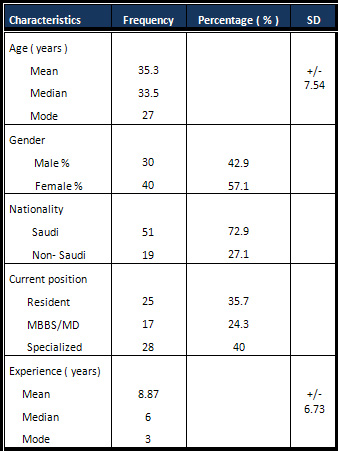

Table

1

shows,

30

(42.9%)

were

male

and

40

(57.1%)

were

female.

Maximum

age

was

58

years

old

and

minimum

age

26

years.

Fifty-one

(72.9%)

were

Saudi,

19

(27.1%)

were

non-Saudi.

The

physicians

position

were

25(35.7%)

residents,

17(24.3%)

MBBS/MD

and

28(40%)

specialists.

The

maximum

years

of

experience

were

25

years

and

minimum

was

2

years.

Table

1:

Demographic

data

of

participants

Table

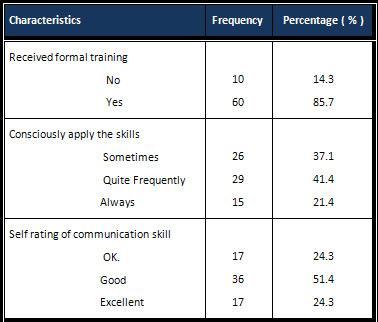

2

shows

that

14.3%

of

the

physicians

did

not

receive

formal

training

about

communication

skills

during

medical

consultations,

while

85.7%

did

receive

formal

training.

Over

two-thirds

of

the

primary

care

physicians

consciously

applied

specific

communication

skills

frequently

in

their

daily

practice.

On

a

self

rating

scale

of

communication

skills

(1-4

scale)

over

75%

of

the

physicians

rated

their

communication

skills

as

good

or

excellent.

Table

2:

Communication

skills:

training

and

attitude

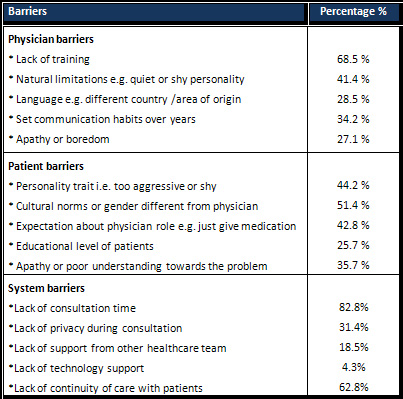

Barriers

of

effective

communication

skills

were

divided

into

three

categories:

physician,

patient

and

system

barriers

[Table

3].

The

two

most

significant

physician

barriers

were

lack

of

formal

training

(68.5%)

and

natural

limitations

e.g.

quiet

or

shy

personality

(41.4%).

The

two

most

significant

patient

barriers

to

communication

skills

reported

by

physicians,

were

cultural

norms

or

gender

different

from

physicians

(51.4%)

and

personality

trait

of

patient,

i.e.

too

aggressive

or

shy

(44.2%).

The

two

most

significant

system

barriers

as

perceived

by

physicians

were

lack

of

consultation

time

(82.8%)

and

lack

of

continuity

of

care

with

patients,

i.e.

patient

seen

by

different

doctor

each

time

(62.8%).

Table

3:

Barriers

to

effective

communication

skills

in

medical

consultation

Click

here

for

Table

4:

Communication

of

skill

practice

pattern

and

PHC

physicians

Table

4

Shows

that

nearly

69%

of

physicians

rarely

or

sometimes

involved

the

patient

in

decision

making;

another

70%

rarely

or

sometimes

discussed

goals

of

consultation

with

their

patients

or

used

'pause

or

silence'

in

communicating

with

their

patients.

Around

2/3rds

of

physicians

rarely

or

sometimes

inquire

about

the

person

accompanying

the

patient.

For

female

patients

there

were

73.2%

of

female

physicians

who

rarely

or

sometimes

felt

the

need

to

ask

their

female

patients

to

remove

their

face-cover

in

daily

practice

to

assess

their

facial

expressions

better.

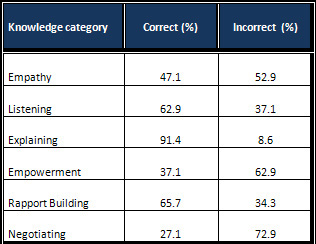

Table

5:

Communication

skills

knowledge

score

percentages

of

physicians

In

Table

5

the

majority

of

empathy,

empowerment

and

negotiating

knowledge

were

answered

incorrectly

while

the

majority

of

listening,

explaining

and

building

rapport

knowledge

were

answered

correctly.

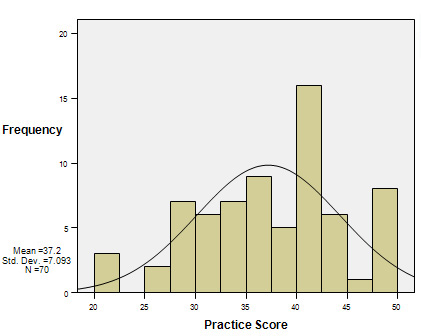

Figure

1:

Distribution

of

practice

scores

among

physicians

The

total

maximum

score

of

practice

questions

was

60.

Figure

1

shows

mean

of

practice

score

37.2,

SD

+/-

7.093,

maximum

score

49

and

minimum

score

20.

Questions

#

13

&

17

were

excluded

from

the

total

score

(See

Table

4).

For

each

question

the

value

ranged

from

1-4.

Total

score

for

each

physician

was

added

and

all

scores

are

presented

in

Figure

1.

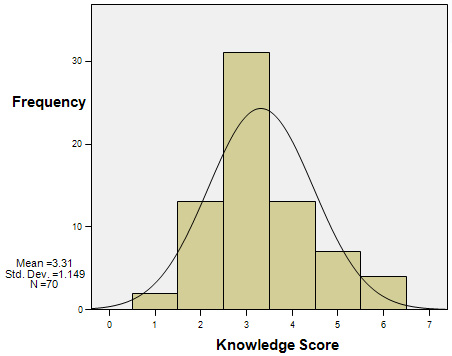

Figure

2:

Distribution

of

knowledge

scores

among

physicians

The

total

score

of

the

knowledge

questions

was

6.

If

a

physician

answered

a

question

correctly

one

score

was

awarded.

Thirty-one

(44.3%)

physicians

scored

3

out

of

6.

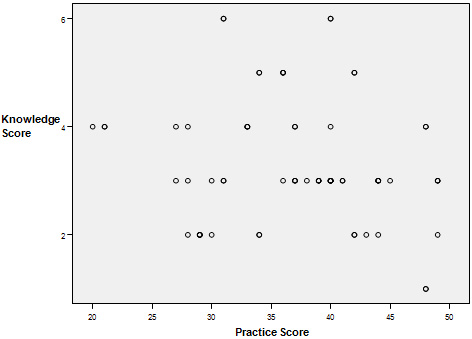

Figure

3:

Relationship

between

knowledge

and

practice

scores

Figure

3

shows

no

relationship

between

score

of

knowledge

and

practice

of

communication

skills

based

on

linear

regression.

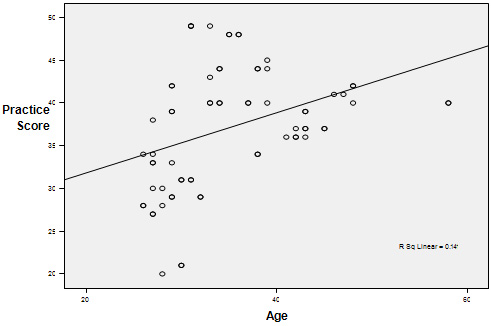

Figure

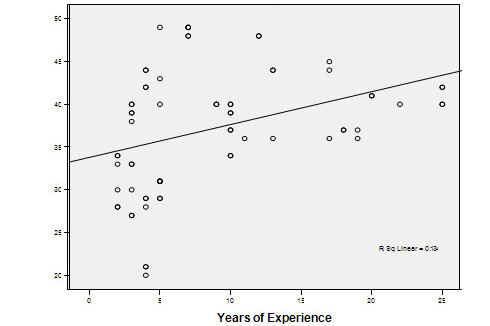

4:

Relation

between

Age

and

Practice

Figure

5:

Relation

between

Years

of

Experience

and

practice

Figures

4

&

5

show

that

age

of

physician

and

years

of

experience

are

positively

correlated

to

practice

scores.

Linear

regression

of

age

and

years

of

experience

with

practice

scores

yielded

an

R

Square

0.143,

F

statistic

5.602

and

P

value

0.006.

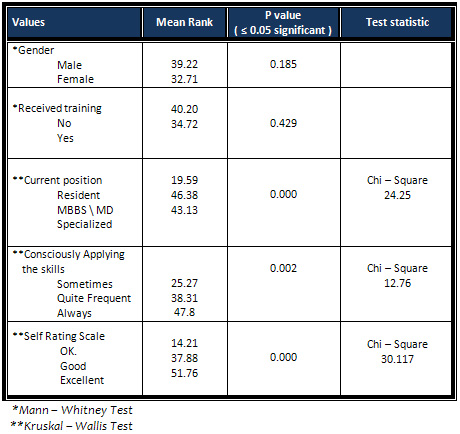

Table

6:

Relationship

of

practice

scores

&

communication

skill

values

The

score

of

practicing

communication

skills

was

found

to

be

not

significantly

different

based

on

gender

of

physicians.

Using

Kruskal-Wallis

Test

it

showed

that

communication

skills

practice

scores

were

significantly

different

between

resident,

MBBS/MD

and

specialists

[Table

6].

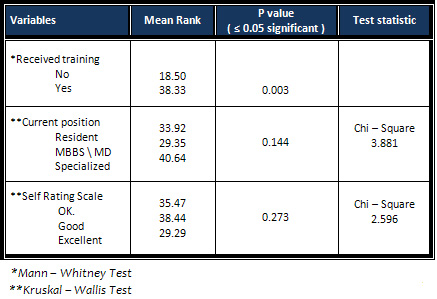

Table

7:

Relationship

of

knowledge

scores

&

specific

variables

The

score

of

knowledge

of

communication

skills

was

significantly

different

based

on

whether

the

physicians

received

training

or

not

[Table

7],

however

there

was

no

statistically

significant

difference

between

the

knowledge

scores

on

the

basis

of

current

position,

self-confidence

of

practicing

skills

or

application

of

communication

skills

consciously.

Multiple

comparisons

was

done

using

Post

Hoc

Tukey

test

between

practice

scores

and

current

position

of

participants.

It

showed

there

is

a

real

difference

between

communication

skills

practice

score

of

residents

with

that

of

MBBS/MD

or

specialized

physicians

but

there

was

no

difference

between

MBBS/MD

practice

score

and

specialized

physicians.

Applying

communication

skills

consciously

was

influenced

by

the

current

position

of

physicians;

most

residents

in

a

sample

(25)

applied

their

communication

skills

rarely

or

infrequently

whereas

23

of

the

28

specialized

physicians

applied

their

skills

quite

frequently,

Chi-square

15.505

and

P

value

0.004.

The

residents

were

less

confident

of

their

communication

skills,

while

MBBS/MD

physicians

and

specialized

physicians

rated

their

communication

skills

as

good

and

excellent,

chi-square

13.754

and

P

value

0.008.

This

study

provides

information

not

previously

available

from

National

Guard

primary

health

care

physicians

on

the

knowledge,

attitude,

practice

and

barriers

of

effective

communication

skills

during

medical

consultation.

The

distribution

of

population

was

almost

equal

between

male

(42.9%)

and

female

(57.1%),

the

majority

of

them

were

Saudis

(72.9%),

between

residents

(35.7%),

specialized

(40%)

and

staff

physicians

(24.3%).

Average

years

of

experience

in

primary

care

ranged

between

2-25

years.

Most

of

the

physicians

did

receive

formal

training

of

communication

skills

in

our

study

(Table

2).

Communication

skills

training

has

been

embedded

in

the

curriculum

of

graduate

medical

and

post-graduate

trainings

for

over

15

years

in

some

parts

of

the

world

[5].

Over

forty

percent

of

physicians

applied

communication

skills

frequently

and

51.4%

rated

themselves

as

good

communicators

(Table

2).

Most

of

the

physicians

thought

that

lack

of

training

(68.5%),

cultural

norms

or

gender

difference

between

patient

and

doctors

(51.4%),

and

lack

of

time

(82.8%)

are

the

main

barriers

to

apply

effective

communication

skills

with

patients.

In

our

study,

one

of

the

main

patient

related

barriers,

as

perceived

by

the

physicians,

was

different

cultural

norms

or

gender

from

that

of

the

physician.

There

is

one

study

that

showed

the

majority

of

patient's

preferred

Saudi

doctors,

suggesting

that

doctor-patient

communication

is

much

easier

when

both

patient

and

doctor

come

from

the

same

culture

[29].

In

the

same

study

most

patients

expected

GPs

to

spend

some

time

explaining

the

nature

of

their

illnesses

and

the

results

of

tests

done

[29].

This

is

consistent

with

the

findings

of

other

studies

[30]

and

this

study,

as

most

physicians

answered

correctly

the

knowledge

question

about

explaining

to

the

patient

in

detail,

as

an

important

communication

skill

(Table

5).

A

study

conducted

to

assess

the

impact

of

two

communication

skills

training

programs

on

the

evolution

of

patients'

anxiety

following

a

medical

consultation

found

no

significant

difference

was

observed.

Results

of

that

study

confirm

results

of

other

studies

that

have

shown

that

some

reassurance

may

produce

anxiety

and

have

suggested

that

communication

skills

are

probably

efficient

if

physicians

discuss

their

patients'

concerns

in

depth

by

using

some

basic

communication

screening

questions

[31].

In

this

study

using

non-verbal

cues

to

communicate

with

patients

were

obviously

rarely

and

sometimes

used

(Table

4).

In

other

studies

they

found

that

patients

offer

clues

that

present

opportunities

for

physicians

to

express

empathy

and

understand

patients'

lives.

In

both

primary

care

and

surgery,

physicians

tend

to

bypass

these

clues,

missing

potential

opportunities

to

strengthen

the

patient-physician

relationship.

Research

on

teaching

communication

skills

demonstrates

that

physicians

can

learn

to

modify

their

communication

style

[32-34].

Despite

widespread

interest

in

the

effects

of

physician

gender

on

the

care

process,

the

literature

describing

these

effects

is

small

[35],

and

in

this

study

there

were

no

differences

between

male

and

female

physicians

in

practicing

communication

skills.

It

was

observed

in

this

study

that

there

was

no

correlation

between

knowledge

and

practice

of

communication

skills

(Figure

3)

suggesting

a

gap

between

knowledge

and

practice.

It

was

also

noted

that

the

physicians

who

consciously

applied

the

communication

skills

in

their

practice,

scored

better

in

daily

practice

of

these

skills

with

their

patients.

The

physician

may

have

knowledge

but

if

he

did

not

make

a

deliberate

effort

to

apply

that

knowledge

in

his

practice,

it

did

not

show

in

his

actual

practice.

Most

residents

received

training

of

communication

skills

during

their

program

but

they

seemed

to

apply

these

skills

in

their

daily

practice

to

a

lesser

degree

than

the

MBBS/MD

and

specialized

physicians

(Table

6).

Communication

skill

training

is

very

important

to

have

knowledge

of

skills

but

having

a

good

knowledge

did

not

affect

the

practice

if

the

physician

did

not

have

the

attitude

of

applying

that

knowledge

in

the

practice

(Table

7).

Specialized

and

MBBS/MD

physicians

were

more

confident

in

their

self

rating

of

communication

skills,

while

the

majority

of

residents

evaluated

their

communication

skills

with

lesser

self-confidence.

This

translated

into

better

practice

scores.

Figure

4

and

5

show

there

is

a

strong

relation

between

age

and

years

of

experience

in

the

medical

field

with

practicing

of

communication

skills.

Years

of

practice

was

found

to

be

a

larger

predictor

of

practicing

communication

skills

when

compared

to

age,

however

both

factors

had

significant

overlap,

suggesting

that

with

increasing

age

and

experience

in

work,

physicians

practiced

their

communication

skills

more.

A

study

showed

that

the

level

of

communication

skills

and

the

content

of

the

consultation

with

regard

to

psychosocial

issues,

patient

concerns

and

the

informing

and

planning

of

procedures

(with

a

representative

patient

in

a

general

practice

setting)

among

graduate

medical

students

are

significantly

correlated;

that

means

having

the

knowledge

of

communication

skills

is

important

[36],

however

in

this

study,

age

and

years

of

experience

were

more

important

than

having

good

knowledge

only.

It

means

that

training

is

important

but

having

self

confidence

and

a

genuine

desire

to

apply

that

knowledge

are

valuable

in

practicing

communication

skills,

which

certainly

improves

with

age

and

experience.

There

are

four

limitations

of

this

study

which

deserve

emphasis:

1.

Small

sample

size.

2.

Study

was

done

among

primary

health

care

physicians

in

National

Guard

which

cannot

be

generalized

to

PHC

physicians

in

Saudi

Arabia.

3.

Majority

of

the

sample

was

Saudi

and

35.7%

were

residents.

4.

Only

six

categories

evaluated

the

knowledge

of

physicians.

This

study

suggests

that

knowledge

base

in

communication

skills

can

improve

with

training

however

having

the

knowledge

of

good

communication

with

patients

does

not

influence

the

practice

of

communication

skills

unless

the

physician

is

self-confident

and

has

the

right

attitude

of

consciously

applying

that

knowledge

in

his/her

practice.

Lastly,

communication

skills

improve

with

age

and

experience.

1.

Younger

physicians

need

to

put

more

emphasis

on

the

use

of

communication

skills;

having

the

knowledge

is

not

sufficient.

2.

Involve

the

less

expert

physician

in

a

teaching

clinic

or

increase

the

number

of

simulated

clinics

during

the

training

of

communication

skills

program

and

improving

the

continuity

of

care

between

physicians

and

their

patients

will

show

good

outcomes

in

improving

the

application

of

those

skills.

3.

How

can

doctors

best

continue

to

develop

their

skills,

apply

them

within

their

daily

work,

survive

emotionally,

and

feel

more

satisfied?

How

can

persistent

behavioral,

perceptual,

and

personal

changes

be

produced?

Self

learning

and

self

monitored

feedback,

distance

learning,

and

serial

workshops

seem

to

be

promising

approaches

for

qualified

doctors.

4.

Finally,

it

is

my

hope

that

the

findings

will

help

in

planning

a

strategy

for

improving

services,

making

effective

communication

skills

attitude

more

acceptable

and

believable

in

the

PHC

sitting

in

our

community

to

improve

patient

care

in

all

aspects.

1.

Haidet

P

,

Dians

JE,

Paterniti

DA,

Hechtel

L,

Chang

T,

Tseng

E,

Rogers

JC.

Medical

student

attitudes

toward

the

doctor-patient

relationship.

Med

Educ.

2002;36:568-574.

2.

Cegala

DJ,

Lenzmeier

Broz

S.

Physician

communication

skill

training:

a

review

of

theoretical

backgrounds,

objectives

and

skills.

Med

Educ

2002,

36(11):1004-1016.

3.

Brown

JB,

Boles

M,

Mullooly

JP,

Levinson

W:

Effect

of

clinician

communication

skills

training

on

patient

satisfaction.

A

randomized,

controlled

trial.

Ann

Intern

Med

1999,

131(11):822-829.

4.

Ong

LM,

de

Haes

JC,

Hoos

AM,

Lammes

FB:

Doctor-patient

communication:

a

review

of

the

literature.

Soc

Sci

Med

1995,

40(7):903-918.

5.

British

Medical

Association

(2004)

Communication

skills

education

for

doctors

an

update.

London:

BMA.

6.

Centre

for

Change

and

Innovation

(2003).

Talking

matters:

developing

the

communication

skills

of

doctors.

Edinburgh:

Scottish

Executive.

7.

Maguire

P

&

Pitceathly

C

(2002).

Key

communication

skills

and

how

to

acquire

them.

BMJ

325:

697-700.

8.

Hulsman

R

et

al

(2002).

The

effectiveness

of

a

computer-assisted

instruction

programme

on

communication

skills

of

medical

specialists

in

oncology.

Medical

Education

36:

125-34

9.

Meryn

S

(1998).

Improving

doctor-patient

communication.

BMJ

316:1922-30.

10.

Feinmann

J

(2002).

Brushing

up

on

doctors'

communication

skills.

The

Lancet.

360:

1572.

11.

Gull

SE

(2002).

Communication

skills:

recognizing

the

difficulties.

The

Obstetrician

and

Gynecologist.

4:107-9.

12.

Spencer

JA

&

Silverman

J

(2004).

Communication

education

and

assessment:

taking

account

of

diversity.

Medical

Education.

38:

116-8.

13.

Sedgwick

P

&

Hall

A

(2003).

Teaching

medical

students

and

doctors

how

to

communicate

risk.

BMJ.

327:

694-5.

14.

Alaszewski

A

&

Horlick-Jones

T

(2003).

How

can

doctors

communicate

information

about

risk

more

effectively?

BMJ.

327:

728-30.

15.

The

General

Medical

Council

(2002).

Tomorrow's

doctors:

recommendations

on

undergraduate

medical

education.

London:

GMC.

16.

General

Medical

Council

(2001).

Good

medical

practice.

London:

GMC.

17.

General

Medical

Council

(1997)

.The

new

doctor.

London:

GMC.

18.

General

Medical

Council

(1998).

The

early

years.

London:

GMC.

19.

British

Medical

Association

(1998).

Communication

skills

and

continuing

professional

development.

London:

BMA.

20.

Royal

College

of

Physicians

of

London

(1997).

Improving

communication

between

doctors

and

patients.

London:

RCP.

21.

Roter

DL,

Larson

S

&

Shintzky

H

et

al

(2004).

Use

of

an

innovative

video

feedback

technique

to

enhance

communication

skills

training.

Medical

Education.

38:

145-7.

22.

Aspegren

K

(1999)

Teaching

and

learning

communication

skills

in

medicine

-

a

review

with

quality

grading

of

articles.

Medical

Teacher.

21:

563-70.

23.

Ministry

of

Health.

Annual

Health

Report.

Riyadh:

Alhilal

House

press;

1418H.

24.

Weis

R,

Stuker

R.

When

patients

and

doctors

don't

speak

the

same

language:

concepts

of

interpretation

practice.

Soz

Preventmed

1999;44(6):257-63.

25.

Saeed

AA,

Mohammed

BA,

Magzoub

ME,

Al-Doghaither

AH.

Satisfaction

and

correlates

of

patient's

satisfaction

with

physicians'

services

in

primary

health

care

centers.

Saudi

Med

J

2001;

22(3):

262-7.

26.

Dube

CE,

O'Donnell

JF,

Novack

DH.

Communication

skills

for

preventive

intervention.

Acad

Med

2000;

75(7

suppl):S45-54.

27.

Hongladarom

S,

Phaosavasdi

S,

Tneepanichskul

S,

Tannirandon

Y,

Wilde

H,

Prukspong

C.

Humanistic

learning

in

medical

curriculum.

Med

Assoc

Thai

2000;

83(8):969-74.

28.

Ahmed

G.

Elzubier.

Doctor-patient

communication:

a

skill

needed

in

Saudi

Arabia.

Journal

of

Fm

&

Community

Medicine

2002;

9(1):30-35.

29.

Khalid

A.

Bin

Abdulrahman.

What

do

patient's

expect

of

their

general

practitioners?

Journal

of

Fm

&

Community

Medicine

2003;

10(1):39-46.

30.

Williams

S,

Weinman

J,

and

Dale

J,

Newman

S.

Patient

expectations:

what

do

primary

care

patients

want

from

the

GP

and

how

far

does

meeting

expectations

affect

patient

satisfaction.

Fam

Pract

1995;

12

(2):

193-201.

31.

Stark

D,

Kiely

M,

Smith

A

et

al.

Reassurance

and

the

anxious

cancer

patient.

Br

J

Cancer

2004;

91:893-899.

32.

Platt

FW,

Keller

VF.

Empathic

communication:

a

teachable

and

learnable

skill.

J

Gen

Intern

Med.

1994;

9:222-226.

33.

Beckman

HB,

Frankel

RM,

Kihm

J,

Kulesza

G,

Geheb

OR.

Measurement

and

improvement

of

humanistic

skills

in

first

year

trainees.

J

Gen

Intern

Med.

1990;

5:42-45.

34.

Roter

DL,

Hall

JA,

Kern

DE,

Barker

LR,

Cole

KA,

Roca

RP.

Improving

physicians'

interviewing

skills

and

reducing

emotional

distress:

a

randomized

clinical

trial.

Arch

Intern

Med.

1995;

155:1877-1884.

35.

Debra

L.

Roter,

Dr.PHJudith

A.

Hall,

PhD

Yutaka

Aoki,

MS,

MHS.

Physician

gender

effects

in

medical

communication.

JAMA

2002;

288:756-764.

36.

Tore

G,

Per

V

et

al.

Observed

communication

skills:

how

do

they

relate

to

the

consultation

content?

A

nation-wide

study

of

graduate

medical

students

seeing

a

standardized

patient

for

a

first-time

consultation

in

general

practice

setting.

BMC

Medical

Education

2007,

7:43-52.

|